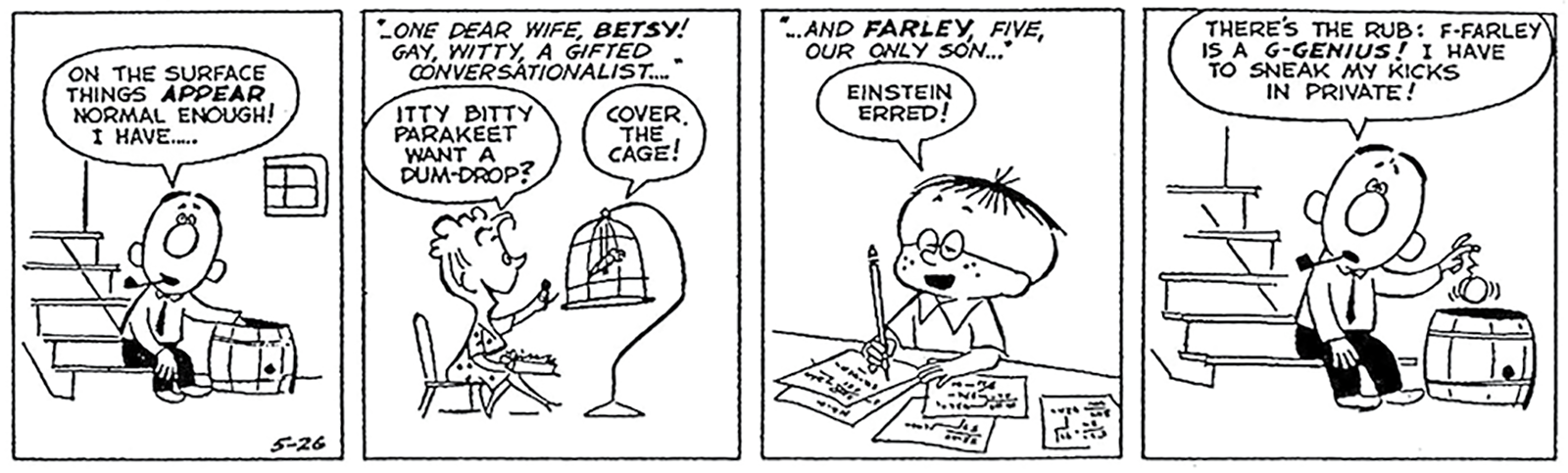

Betsy and Me: A Perversion of Reality

Creator: Jack Cole

Debuted: May 26, 1958

Chicago Sun-Times

Run: Just more than seven months, with Cole’s last strip appearing on September 21. Dwight Parks carried on the story until December 27.

Creator: Jack Cole

Debuted: May 26, 1958

Chicago Sun-Times

Run: Just more than seven months, with Cole’s last strip appearing on September 21. Dwight Parks carried on the story until December 27.

When Hugh Hefner founded Playboy in 1953, he branded it as a lifestyle magazine. It soon grew into an empire. Critics argue both that Playboy played a central role in the sexual revolution and that it denigrated women. No matter where one falls on that spectrum, this much was undeniable: it launched careers. And not just for aspiring models. Unlike the daily comic strips and burgeoning comic book industry, Playboy comics were generally one- offs, gags that appealed to an almost-exclusively male readership. But it was well-paying, high-profile work that helped bolster the versatile careers of Chicagoans like Robert Brown, Shel Silverstein, Gahan Wilson, Phil Interlandi, and, finally, Jack Cole.

Jack Cole, the creator of Plastic Man, was already a comic book veteran in 1954 when he produced the first of his full-page watercolor cartoons for Playboy’s fifth issue. Cole became an undeniable Playboy superstar. A cocktail napkin set (“Females by Cole”) became just the second merchandizing piece licensed by Playboy.

When the Sun-Times bought Betsy and Me, it was Cole’s first daily comic strip. Chester B. Tibbit, the narrator, listlessly works as a department store floorwalker. He experiences what should be the high points of middle class life: marriage, fatherhood, and, finally, he plans to buy a new tract house in suburban Sunken Hills. But realities contradict the superficial delights. In fact, the seemingly earnest storylines amount to a criticism of the post-war push for respectable, sedentary lifestyles.

Cole killed himself just two and a half months after the strip’s debut.

Cole was part of a stable of Playboy cartoonists. Hefner, himself a failed cartoonist, admired the art form and from the start sought out the best talent available. He paid exceedingly well. “Playboy, in other words, was where a gifted cartoonist could get good money to work blue,” Michael Cavna recently wrote in the Washington Post. “You could go off-color in crisply reproduced color. For decades, the top artists kept arriving.”

The one-panel drawings of Playboy and other slick magazines like Esquire were considered a class up from comic books, but not quite the pinnacle of a daily comic strip. But banking money and building reputation enabled greater things. And working for a liberated publication like Playboy allowed artists to explore life and culture in ways forbidden in the mainstream market.

Chicago Literary Hall of Fame

Email: Don Evans

4043 N. Ravenswood Ave., #222

Chicago, IL 60613

773.414.2603