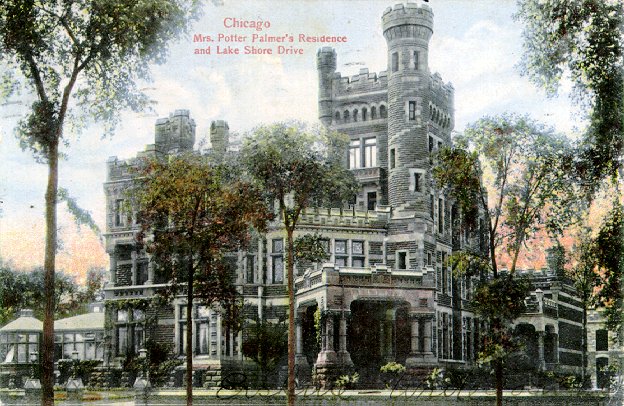

Palmer Mansion, aka “The Castle”

by Olivia Shay

Previously located along Lake Shore Drive, the Palmer Mansion took up an entire city block on property once considered a “wasteland” due to its vacant quality. This area would soon transform into the epicenter of Chicago’s emerging Gold Coast. To complete their lavish mansion, the wealthy Palmers, Potter and Betha Honoré, commissioned the city to construct a road bordering the lake. This road, later known as Lake Shore Drive, provided a picturesque path for the couple to stroll and ride their carriage.

The Palmers married in 1871, the same year as the Great Chicago Fire. As a wedding gift to Bertha, Potter Palmer had built the original Palmer House Hotel, but due to the devastating fire, it was destroyed along with 32 other Palmer-owned buildings. Nine years later, in 1882, Potter Palmer commissioned architects Henry Ives Cobbs and Charles Frost to construct one of the largest residential homes in Chicago. This time, Potter ensured that the building was fireproof, according to Chicagology.

Thanks to Bertha Honoré Palmer’s passion for art and society, the sprawling estate became a cultural hub for late 19th-century artists and affluent people. The couple hosted exclusive events that attracted artists and the city’s elite, showcasing their curated art collection within the home. One particular party the couple threw was their annual New Year’s Eve party — a celebration that blended opulence with artistic sophistication which attracted many of Chicago’s elite and influential. Mrs. Palmer made sure that the invitations were status-endearing and personal. According to americanaristocracy.com, the mansion was without doorknobs or locks, exemplifying its exclusivity and status as a sanctuary for the privileged.

Potter Palmer founded Potter Palmer and Co. - a dry-goods grocery store with a “no questions asked” return policy in 1852. The return policy was of great appeal to the Chicagoans and made the company famous during the late 19th century. According to the University of Michigan, in 1867, Potter sold his business to Levi Leiter and Marshall Field due to stress and a desire to focus on his real estate growth. This change did affect him financially, but through private sources, Potter was lent $1.7 million to rebuild the hotel now known as the Potter House Hilton. The Potter House Hilton made Palmer a staple in Chicago’s real estate.

Bertha Palmer was a significant character in Chicago’s high society of the 19th century. At the mansion, she hosted charity balls, fundraisers, exclusive parties, and celebrations. According to the Art Institute of Chicago, she was a member of many clubs and associations in the late 1800s, most notably the Chicago Women’s Club and Chicago’s Gilded Age Society. Bertha Palmer was also the founder of the Chicago Society of Decorative Arts — now known as the Antiquarian Society in the Chicago Art Institute. The mansion was built in her honor by her husband and she used it well. Bertha’s status and power allowed her to collect art and hang it throughout the house. She discovered her love of art while traveling through Europe to assist in the organization of the World’s Columbian Exposition, a fair Chicago would host in 1893. At the fair, she was named the Chairman of the Board of Lady Managers. She invited her friend and poet, Harriet Monroe, founder of Poetry Magazine, to open the fair with her poem “The Columbian Ode.”

Bertha Palmer was an admirer of the classics. She went so far as to edit a collection of classic literature titled, “Stories from the Classic Literature of Many Nations” in 1898. Pieces included, but not limited to, in the anthology are “The Odyssey” by Homer, “The Arabian Nights” a storybook by different authors from the Middle East, and "The Nibelungenlied" by an anonymous author from Germany.

Bertha organized her collection of art in multiple rooms throughout the mansion, but most of the work was organized into a 90-foot ballroom, purely used to display her collection. She discovered the action of collecting art through Sarah Tyson Hallowell, for whom Bertha later became an art advisor. The pieces were organized by the different art movements that they were created in. Her favorite collected piece was Renoir’s Acrobats at the Cirque Fernando. She loved this so much that she would take it to Europe when she traveled there. Much of the art she collected hangs in the Art Institute today.

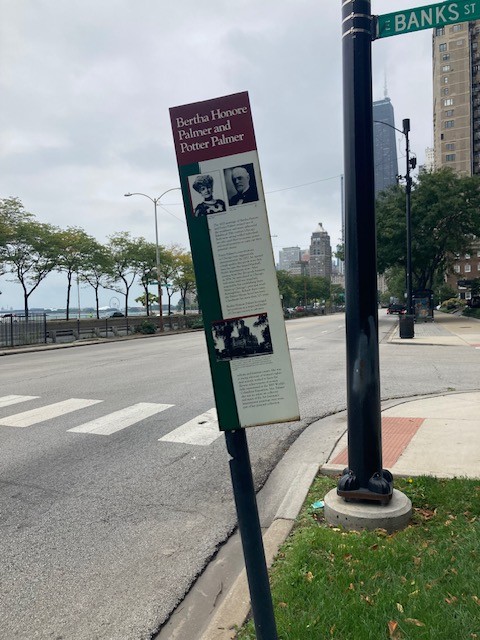

After the deaths of both Palmers, Potter in 1902 and Bertha in 1918, the mansion was passed down to their son, Potter Palmer Jr., then later Vincent Bendix. The mansion was repurposed into a Red Cross surgical dressing center between 1942 and 1943 for soldier’s returning from the war. The mansion was demolished in February of 1950 as people saw it as a ghost haunting Chicago of the past. A Chicago Tribute Marker of Distinction stands at 1359 N. Lake Shore Drive to honor the contributions of Bertha and Potter Palmers to Chicago life.

A Tribute Marker of Distinction stands at the

site where the Palmer Mansion once stood.

(Photo by Donald G. Evans, 2024).