"One thing about Chicago, he thought; even in the ghetto there are trees and grass."

from The Spook Who Sat by the Door

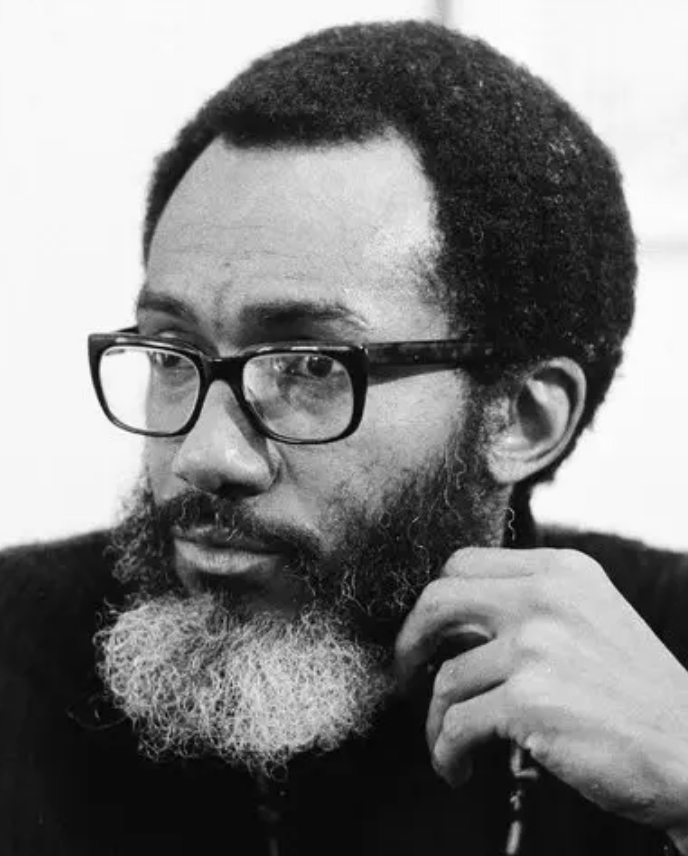

You could find Sam Greenlee at Daley’s, on East 63rd Street, selling DVD copies of The Spook Who Sat by The Door. He’d tell you the DVD was free, but his signature was twenty bucks, and he’d tell you he was “bootlegging his own movie.”

That movie, and the novel upon which it was based, is Greenlee’s lasting legacy, but more so it represents the life he lived in and for his Woodlawn community. Greenlee wrote the screenplay and raised the money among his own people—no Hollywood investors, no speculators, no white art patrons—and the cult classic film continues to be talked about and seen more than 40 years after its initial release.

“Sam represented a voice of consistency,” says Pemon Rami, who played Shorty Duncan in the film and remained close friends with Greenlee the rest of his life. “He was consistent in his message: consistent in his message to the city, consistent in his revolutionary fervor, consistent in his criticism of things affecting the community. People loved him for that.”

Greenlee was born in Woodlawn to a railroad worker and chorus dancer, and raised primarily by grandparents. He attended local public schools, matriculating along with Lorraine Hansberry all through grade and high school. He was just a sophomore at Englewood High School when he participated in his first sit-in and walked his first picket line. His activism would define his life until the end. His State Department career and his academic pursuits took him away from Chicago for long periods, but he remained close to the community throughout his life. He saw the neighborhood through various incarnations, from relatively prosperous days through the worst years of gang violence and then a return to sanity. He walked, he biked, he bused, in his later years he rode his wheelchair through the streets of Woodlawn.

“He was hardly at home except to read, or listen to jazz,” said his daughter Natiki Pressley. “He liked the outdoors. He rode his bike or went on long walks. We’d go to a lot of restaurants. I don’t ever remember going to a place where nobody knew him.”

It was Greenlee’s experience in Baghdad in the 1950s, during the Revolution, that provided fodder for Spook. Sam was a member of the United States Information Agency, a branch of the State Department. He returned to Chicago to witness racism and other atrocities happening in his black community, and according to Rami, “he made some choices.”

“When he was a young writer, he could have done anything: he could have done fluff, frivolous comedy. He chose to make a movie that represented what he felt, and what our community needed to connect, to be committed, to the resurrection of our community.”

The novel’s protagonist, Dan Freeman, gets a token position as the first Black C.I.A. officer, and he tolerates a brief, demeaning career in order to learn and bring home to Chicago the intricacies of revolution. Freeman’s experience provided him with the knowledge and experience to make Molotov cocktails, hold up banks, and steal firearms. The popularity of the story relies on the clever plot, in which young Black men use the White establishment’s own power against it. This form of social justice, while criticized by some, appealed, if only as a fantasy, to a segment of the Black population running short on patience.

The film, directed by Ivan Dixon and starring Lawrence Cook, won inclusion in the National Film Registry’s catalog of American movies, a testament to the story’s lasting cultural significance. Herbie Hancock, an old friend of Greenlee’s, provided the movie’s score. A remastered version by Tim and Daphne Reid was released on DVD in 2004. Sunday Times (London) named the novel, which eventually sold more than a million copies in six languages, its Book of the Year.

But while Greenlee’s legacy resides firmly in the acclaim of his most successful novel, his oeuvre includes another fine novel, Baghdad Blues (Black Issues Book Review listed it as one of 1976’s bestselling books by a black author), as well as three collections of poetry. He wrote a number of stage plays, journalistic pieces, short stories, and left an unfinished memoir and another novel, Djakarta Blues. Greenlee’s interest in Greek culture, cultivated while living and studying on the island of Mykonos in the Aegean Sea, manifested itself in an adaptation of Lysistrata. He taught screenwriting at Columbia College Chicago and hosted a radio show on WVON.

“Sam was really a poet, a very good poet,” said Useni Eugene Perkins. “He knew a lot about history. Sam was somewhat of a scholar; he could talk about many subjects because he was well read.”

Greenlee was named Illinois Poet Laureate in 1990, one of many notable recognitions he received throughout his life, including a 1989 Ragdale Foundation fellowship, a 1990 Illinois Arts Council fellowship, and induction into Chicago State University’s National Literary Hall of Fame for Writers of African Descent. He was also given the meritorious service award for bravery during the 1958 Baghdad revolution.

“Sam, though extremely erudite, chose to use a language that made his art readily available to the man and woman on the street,” said the poet Sterling Plumpp. “That was a choice, it was not a limitation for Sam. They were the people that he cherished in his novels. His poetry is pithy, and highly ironical.” Plumpp names Ammunition! as Greenlee’s finest collection, saying that it best captures “the scope of his vision.”

Greenlee’s memorial service, held at the DuSable Museum, demonstrated the author’s long reach through Chicago and beyond. The museum swelled with people who knew Greenlee as a friend, family member, or colleague, including prominent figures such as Rami, Plumpp, Tim Reid, and Robert Townsend. But it also was packed with people who knew Sam as a fixture in the neighborhood, or through his work.

“They all knew him,” said Rami. “They respected him because he had a love for that community, and he stayed there, that was his home. And he always went home.”

Poet and Third World Press publisher Haki Madhubuti, who was instrumental in the publication of Greenlee’s first book of poetry and his recognition at Chicago State University, said, “He was a good man, and a fine poet.”

Pressley acknowledged that community, perhaps above all else, ranked as her father’s greatest concern. “He believed it was important to be independent and for our community to support ourselves. Art should come from us, but also the finances.”

For Greenlee, his art and his life seemed inseparable, and his masterful output relied on the Chicago to which he was born, raised, and forever devoted, no matter how far his adventures took him.

“Part of the greatness of Sam Greenlee was his experience in growing up in Woodlawn,” said Plumpp. “Sam grew up in a Chicago where you had full-blown African American communities that were not full-blown ghettos. It was a vibrant community that produced Lorraine Hansberry, Richard Hunt, Oscar Brown, Jr., Willard Motley and his brother, Gwendolyn Brooks. You had Margaret Burroughs, the South Side Community Arts Center, Tim Black, the same community that produced Harold Washington, Nat King Cole. It was a healthy African American community that was confined by race to a specific space, but never had downcast eyes. Eyes were always focused on the sky.”

read less