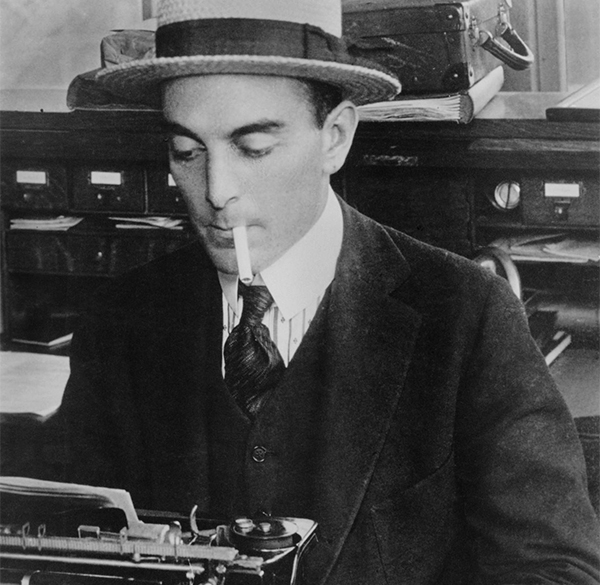

Ring Lardner thought of himself primarily as a sports writer, though many of his generation’s best writers considered him one of the finest short story writers and a great American humorist. Ernest Hemingway, writing for his Oak Park high school newspaper, even used the pen name “Ring Lardner, Jr.” in several Lardner-like articles parodies of Lardner’s style, which that employed the slang of common lowbrow characters. Born in Niles, Michigan, Lardner went to Chicago’s Armour Institute to study engineering, but failed every class except rhetoric. He scuffled around a bit, received a newspaper apprenticeship at the South Bend Times, then returned to Chicago in 1907. Working on a series of Chicago dailies, Lardner…

read moreRing Lardner thought of himself primarily as a sports writer, though many of his generation’s best writers considered him one of the finest short story writers and a great American humorist. Ernest Hemingway, writing for his Oak Park high school newspaper, even used the pen name “Ring Lardner, Jr.” in several Lardner-like articles parodies of Lardner’s style, which that employed the slang of common lowbrow characters.

Born in Niles, Michigan, Lardner went to Chicago’s Armour Institute to study engineering, but failed every class except rhetoric. He scuffled around a bit, received a newspaper apprenticeship at the South Bend Times, then returned to Chicago in 1907. Working on a series of Chicago dailies, Lardner started to earn a reputation as one of the smartest, funniest and most insightful baseball writers of his day. In 1913, after a detour to St. Louis and Boston, Lardner accepted the Chicago Tribune offer to install him as columnist of the popular “In the Wake of the News,” which expanded his repertoire beyond sports. He wrote the column seven days a week until 1919, more than 1,600 columns. During this time, Lardner began selling baseball stories to the Saturday Evening Post, and those stories were eventually collected into his first major work, an epistolary novel called You Know Me, Al, which centered around the travails of minor league pitcher Jack Keefe.

Though Lardner is known for his baseball stories, only about a third of his 130 short stories were written on the subject. He also explored subjects such as marriage and the theater, and wrote a series of plays, the most successful being June Moon, a musical comedy for which he also wrote songs. He also is wrote lyrics and comic sketches appeared in for the Ziegfeld Follies, including one in which Will Rogers played a veteran pitcher. His best known collections include Treat ‘Em Rough, The Big Town, How to Write Short Stories, Haircut and Roundup. His biographer, Donald Elder, called Lardner the “most ferocious satirist since Swift.” In 1990, his name was engraved on the frieze of the Illinois State Library alongside other great Illinois literary figures.

The legion of Lardner supporters, beyond Hemingway, includes his era’s greatest intellectual writers, including Dorothy Parker, H.L. Mencken, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Virginia Woolf, and Harold Ross. It’s true that Lardner won high praise, vast readers, and many admirers for his sharp sports writing. His style, approach, the way he interacted with the games and personalities he covered, broke new ground, entertained and informed, and made people laugh. But Lardner’s reach was so much more extensive. His ear for dialect, and skill with vernacular, helped Lardner translate a rough but sensitive American spirit to his readers, and a new technique to aspiring writers. Mencken called his characters “thoroughly American,” and Woolf thought he used games, much like the English used society, to penetrate the interior of his nation’s consciousness.

read less