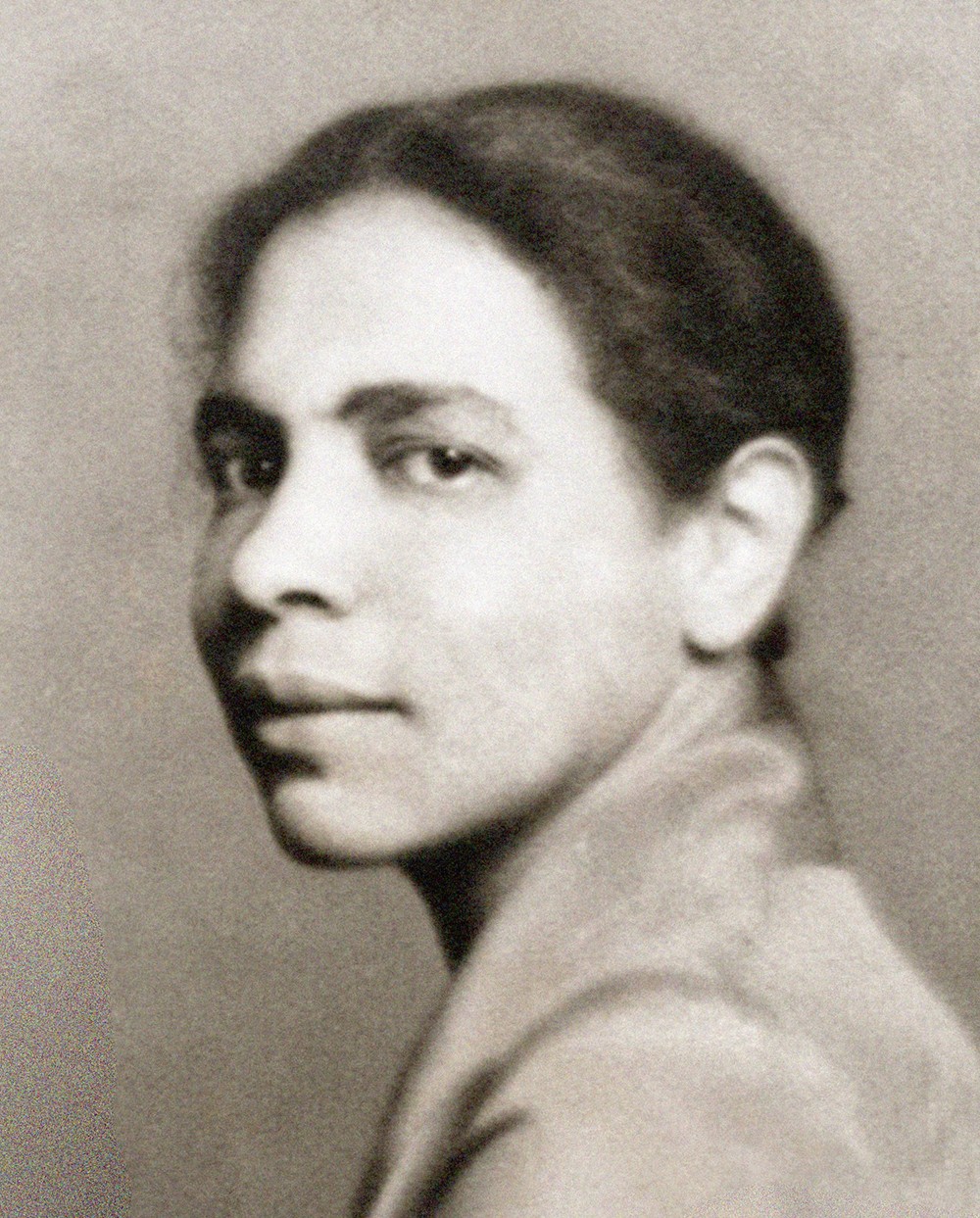

Nella Larsen is commonly associated with the Harlem Renaissance, yet she was a Chicago native whose personality was decisively shaped by her youth on the near South Side. The Chicago of her early childhood was a sprawling chaos sprung from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1871 and already surpassing in population every American city but New York. “Think of all hell turned loose,” wrote the newcomer John Dewey to his sister in 1894, “& yet not hell any longer, but simply material for a new creation.” Born in 1891 at 2124 S. Armour Street (Federal Street today) to a white Danish immigrant named Marie Hansen and a man of color named Peter Walker from the then-Danish Virgin Islands, Larsen (initially Nellie Walker) grew up in one of the Western Hemisphere’s most notorious vice districts, the so-called Levee. Prowling the area bordering Nella’s to the north, the young journalist Theodore Dreiser wrote in his first feature newspaper story, “Entering the district at midnight and wandering along the broken wooden pavement, ill-lighted by lamps and avoided by the police, the nerves tremble at the threatening appearance of the whole neighborhood.” He could see only filth, misery, and vice in the area--drunken men and despondent women, children with “wan, peevish faces.”

Peter Walker abandoned his wife and daughter soon after Nella’s birth, and Marie could not legally remarry for seven years, but she took up soon after Walker’s disappearance with a white Danish immigrant named Peter Larsen, and they considered themselves married. Marie gave birth to a second, white daughter when Nella was a year old; both daughters were given the Larsen surname and grew up in a Danish-American home. Residential segregation was already an issue but there was no true “ghetto,” because African Americans were still so few. As of 1890, only one point three per cent of the Chicago population was black. By 1910 the number had risen to just two per cent, but a distinct “black belt” had taken form. As a “mixed” working-class family in rapidly segregating Chicago, the Larsens were forced to live in the red-light district, and Larsen’s relationship to the black community was tenuous. Being born to a white woman was enough in itself to cast suspicion upon her legitimacy. Knowing little about her natural father throughout her life made the situation even worse. White women with mixed-race children were routinely assumed to be prostitutes. For young Nella Larsen, the racial culture of the United States imperiled her primary attachments and vexed every aspect of her family’s life. To be identified with her mother, to be carried on her mother’s hip in the butcher shop, to toddle down the sidewalk at her sister’s side, meant braving catcalls and dirty looks.

For a period of their early youth before starting school, Nella and Anna accompanied their mother to Denmark to live with relatives, apparently for three years, while Peter Larsen moved to the “white” West Side. They returned to Chicago in 1898 after Marie’s mother died and the family promptly moved back

to the vice district at State Street and Twenty-Second Street. Seven months later Marie and Peter Larsen were finally able to legally marry, the seven-year waiting period having elapsed since Peter Walker’s disappearance.

In adulthood Larsen would be less than forthcoming about her early life and allowed people to assume she came from a bourgeois background. Many who knew Larsen later in her life in New York were fully aware of the reputation of her birthplace. Many had lived in Chicago themselves. If queried on the issue of her parentage, Larsen had little defense at a time when being thought the illegitimate “mulatto” daughter of a white woman would have devastating consequences for any attempt to “make it” in respectable society, a fact that is foundational to Larsen’s first novel Quicksand (1928).

Larsen’s stepfather became a streetcar conductor and her mother a dressmaker, a skilled trade particularly identified with Scandinavian women. As they became more financially secure, they moved to a working-class stretch of State Street in the 4500 south block, in an area with several other “mixed” families as well as black ones. In general, however, the white families were gradually moving out. Chicago’s great labor battles, in Larsen’s own neighborhood, quickly started turning into white race riots as capitalists brought in black workers from the South to break the unions. Black people, excluded from most unions, became automatically equated with “scabs.” Soon white families moving up from the southern border-states began complaining about racially mixed social events in the public schools and the integrated cafeteria at Larsen’s high school. A few black and “mixed” families moving into “white” neighborhoods around

Kenwood had their homes bombed, and neighborhood covenants took form to maintain racial “deadlines” at Wabash Avenue to the east and Wentworth to the west. The black belt that Richard Wright would write about in Native Son was taking form.

Larsen nonetheless did well in school at a time when Chicago public schools were considered among the most progressive in the nation. English classes assigned “modern” literature and encouraged creative writing. Larsen graduated eighth grade and spent two successful years at Wendell Phillips High School, the most integrated in the city by far. This at a time when only 12,400 Chicagoans enrolled in secondary school out of a population of two million. There being very few vocational options for working-class black girls, Larsen’s parents clearly knew that Nella would have to somehow find a way into a profession, and into the black world. In contrast, Nella’s white half-sister never even attended high school; nor did the two girls ever attend the same primary school, although they were only a year apart. Marie Larsen was especially concerned that her first daughter receive good schooling--an education far better than the average for working-class people. In 1907 Marie Larsen’s dressmaking--along, perhaps, with the help of a recently arrived uncle from Denmark--enabled the family to send Nella to Fisk University’s Normal School for training black teachers. Fisk educated the children of the nation’s black elite, and many marriages came out of there.

In the same year Nella took the train south to matriculate at Fisk, her stepfather and mother bought a house on West 70th Place, in a “white” neighborhood only a few blocks away from the Chicago Normal School, which Larsen could have attended for free. Nella never lived in Chicago for an appreciable time thereafter. When she was expelled from Fisk after only a year, apparently over a student rebellion against the dress and social codes for girls, Nella went to live with her mother’s people in Denmark. Her Chicago years were over, but they left an enduring imprint on her personality. The relentless pressures on her most intimate relationships bred a constant fear of abandonment she would never be able to shake. Keenly sensitive to the stigma of blackness, on the one hand, and that of presumed illegitimacy on the other, she adopted a protective mask of diffidence and intense self-restraint. As much as she longed for intimacy, she would always be ready to break off with people before they could break off with her. She was used to being on the outside, attentive to hypocrisy and accustomed to slights. She approached group identity cautiously. To what “group,” after all, had Nella Larsen ever really belonged? Groups had always

spelled trouble for her, inhabiting as she had the bristling borders along which they faced off.

Denmark did not ultimately work out for Nella Larsen, either. She returned to America after three years, promptly entering a black nursing school in an almost all-white hospital in the Bronx. Becoming a highly-regarded nurse and nursing educator, Larsen managed to rise into the black bourgeoisie after a stint at Tuskegee Institute and marry a cosmopolitan man of good family, America’s first black PhD in physics. She then turned to library work, becoming the first black graduate of a professional library school, and found herself, as the Harlem Renaissance took form, on the springboard to a literary career. Her first publications introduced black children to Danish children’s games and rhymes in The Brownies’ Book, a black children’s magazine associated with The Crisis, a journal of the NAACP in New York. Her highly autobiographical first novel, Quicksand, established her as one of the leading fiction writers of the Renaissance and was quickly followed by Passing, an even more admired work. In both novels, the protagonists are natives of Chicago who straddle the black/white divide and have been profoundly shaped in childhood by the city’s racial culture before moving to New York as adults. Passing earned Larsen a book award from the Harmon Foundation and a Guggenheim Fellowship to travel in Europe and North Africa while working on another novel. She was the first black woman so honored.

But even as these honors came and she started work on a third novel, her marriage disintegrated. Her husband had begun an affair with a white administrator at Fisk whom Larsen knew, and Larsen began spiraling into depression. Her novel, apparently about a white suburban couple with marital problems, was rejected. (The manuscript has never been found.) Larsen survived on alimony for some years, and after her ex-husband died in 1941 went back to nursing, ultimately becoming a head nurse at a hospital on New York’s multi-ethnic Lower East Side and then at Metropolitan Hospital serving the Upper East Side and East Harlem. Forced to retire at the age of seventy-one, within a year she passed away from a heart attack, over Easter weekend, alone in her apartment on Second Avenue near 18th Street. Her body was discovered by the building supervisor.

When her white half-sister, now living in California, heard that she was to inherit some money from Larsen, she exclaimed, “Why, I didn’t know I had a half-sister!” But she did know, and there was no need for the ruse. Even the friend she said this to, Mildred Phillips (also raised in Chicago), knew about Anna’s dark halfsister, Nella. Marie Larsen had spoken of her to Mildred’s mother many years before. But Mildred had known never to ask Anna or Marie about the “other” Larsen daughter, and never heard her mentioned in either Marie’s or Anna’s homes. Larsen was buried in Brooklyn in an unmarked grave by a former black nursing friend, in that friend’s family plot.

For several decades, Larsen’s novels were largely forgotten. In the 1960s, with the rise of the Black Arts Movement, they were dismissed as “rear guard” attempts to prove to white people that some Negroes in America were just like them, with refined European manners and nice belongings, who ought to be allowed into white people’s churches and homes. Such was the critical consensus when Larsen’s novels were first reissued and began to be discussed in university classrooms in the early 1970s. Biographical speculation about her was often wildly inaccurate. In the late 1980s and 1990s, her work was rescued by black feminist critics constructing an alternative womanist tradition to balance the folk orientation of Zora Neale Hurston; but this reclamation came at the expense of her consciously interracial position, and the story of her life retold in a way to deny much of her life experience, particularly her ties to her mother’s family and her claims of having lived in Denmark, which were now viewed as pathetic attempts to play up her “whiteness.” In related fashion, her novels were critiqued for their allegedly superficial emphasis on mulatto characters and passing, which had prevented her from more boldly investigating her real theme--black female sexuality, black sisterhood--and had compromised their literary value. In the twenty-first century the buried record of her life in scattered and unexpected archives was finally corrected. At the same time, her novels have come to be recognized as among the most psychologically probing investigations we have of America’s color line culture, of the reproduction of the black/white divide, and the roles of gender and sexuality in sustaining that divide. She would undoubtedly be proud, if somewhat surprised, to find herself in the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. It is surely where she belongs.

George Hutchinson

read less