BETTE HOWLAND: THE TALE OF A FORGOTTEN GENIUS

How Brigid Hughes Discovered a Lost Writer,

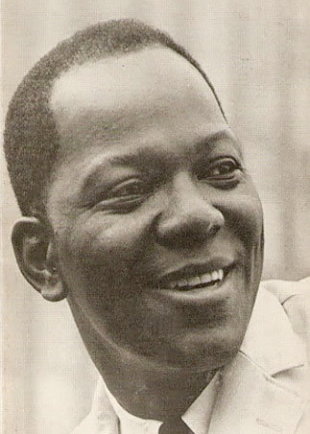

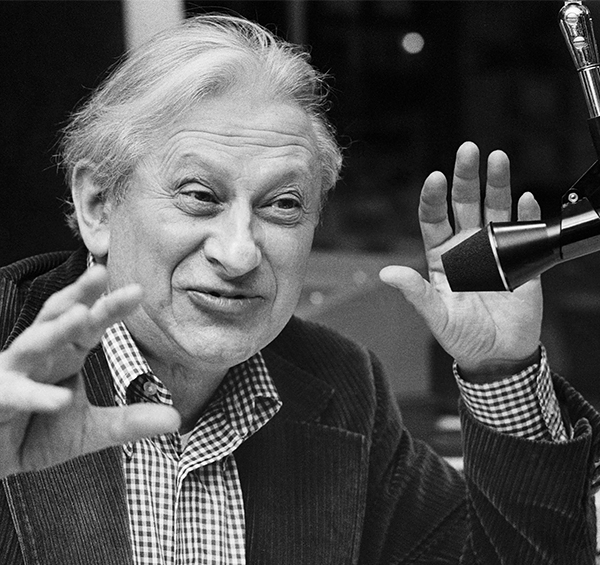

and Her Letters from Saul Bellow

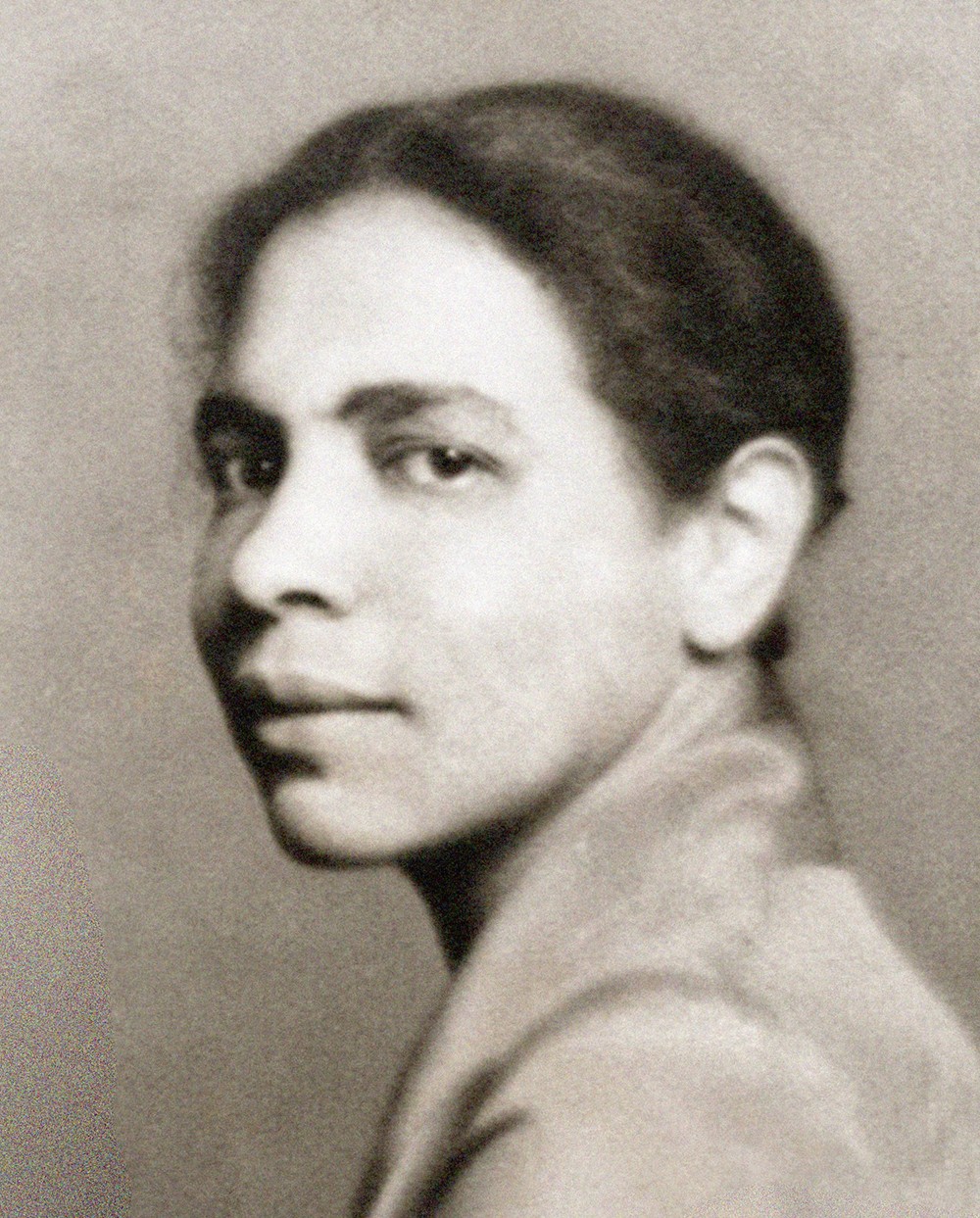

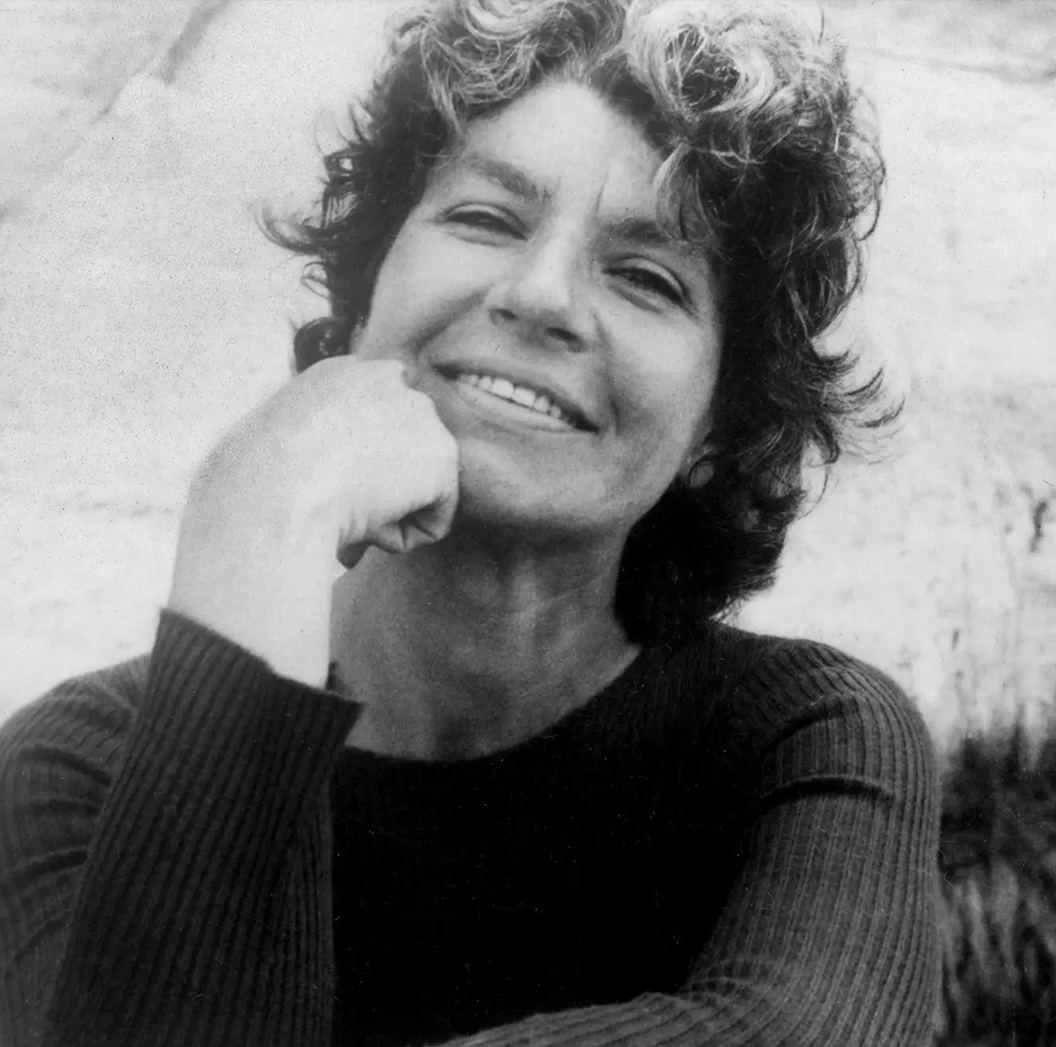

In 1984, writer and critic Bette Howland won a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship.

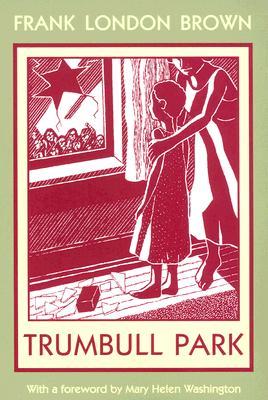

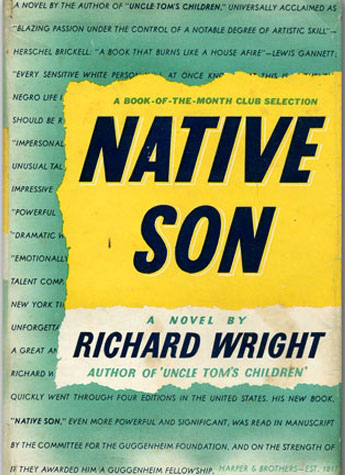

In 1983, she published Things to Come and Go: Three Stories. In 1978 she published her first story collection, Blue in Chicago. The same year, she won a Guggenheim Fellowship. Her first book, the memoir W-3, was published in 1974.

On June 2, 2015, Brigid Hughes, editor of the Brooklyn-based literary magazine, A Public Space, was browsing through the cart of books priced $1.00, the castoffs, at Manhattan’s Housing Works Bookstore, when a book caught her eye. She didn’t recognize the author, but she picked it up with a few other books and went home and started reading it.

Here are the first sentences of W-3:

In the Intensive Care Unit there was a woman who had undergone open-heart surgery. A monitor was implanted in her heart; it beeped every second of the day and night, a persistent tempo, never racing or slowing down as a human heart seems to, unaccountable times on the most ordinary days of our lives. If it had, the nurses would have been there on the double, their brisk white heels disappearing behind the swaying curtains. The woman was unconscious, she had never come out of it; her life was just a mechanism--its regular pace audible all through the ward.

I must have been hearing this beeping sound for a long time before I knew it.

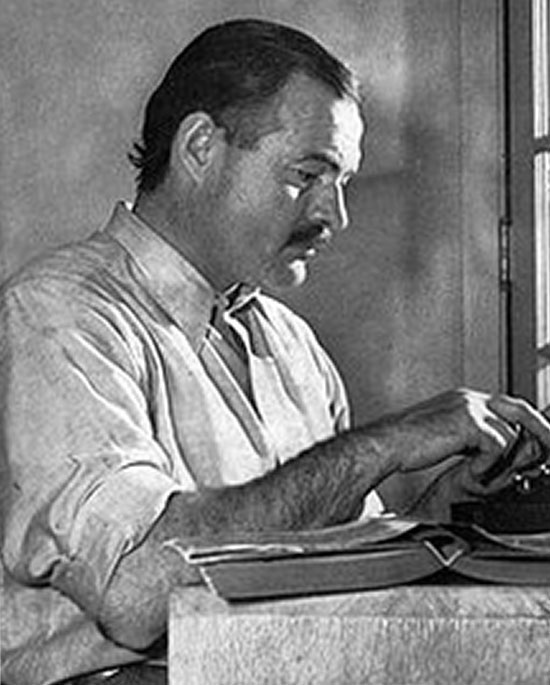

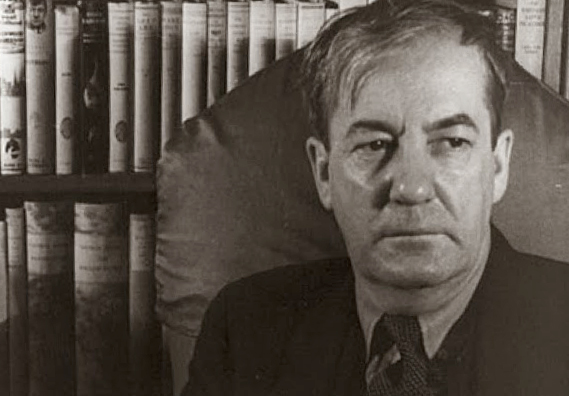

Hughes had stumbled upon the memoir that launched Howland’s career. Howland’s title, W-3, refers not to the government tax form, but to the name of the psychiatric wing of a Chicago hospital. In 1968, Howland was a single mother of two boys, piecing together an income from low-paid librarian shifts and editorial work for the University of Chicago Press. The daughter of Jewish immigrants, she had married a Mayflower descendent, but they divorced. After that, she had no family support. The winter’s chill, the poverty, the providing-on-a-shoestring, became too much. She swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills one afternoon and was hospitalized. It so happens that at the time of their taking, she was in Saul Bellow’s apartment while he was traveling overseas.

It’s a safe bet that if Hughes, who prior to starting A Public Space in 2006 edited The Paris Review after George Plimpton’s death, hadn’t heard of Howland, then those in-the-know in the literary world hadn’t either. All three of her books are out-of-print, and since winning the MacArthur she hadn’t published another book.

(Full disclosure: I rent a desk at the offices of A Public Space, and volunteered at the magazine in graduate school. I saw the striking cover of W-3 on Hughes’s desk and then nosily interrupted her to ask what the book was. “Funny you should ask,” was her reply, “That was my reaction when I saw the book, too.” That night, unable to contain my curiosity, I went home and ordered my own W-3, as well as Howland’s other books.)

The mystery of Howland’s life, and her writing, and why she wasn’t more known even in literary circles, drew Hughes in entirely. She had earlier in the year started to think about forgotten women writers, and about the feasibility of focusing an issue of the magazine on them, if she could find them. The seed of the idea emerged from a lecture by another off-the-radar writer, 78-year-old Martha King, about her time in 1955 at Black Mountain College. She spoke about how isolating and difficult the pursuit of independent work is, how recognition is fleeting and rarely received.

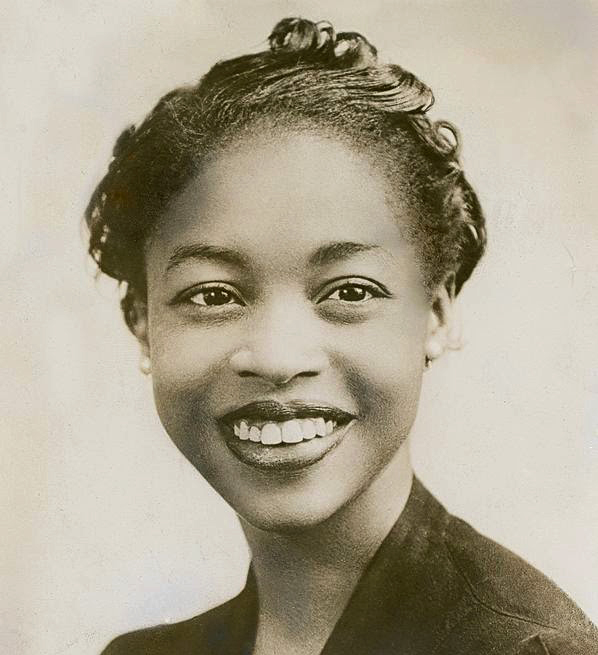

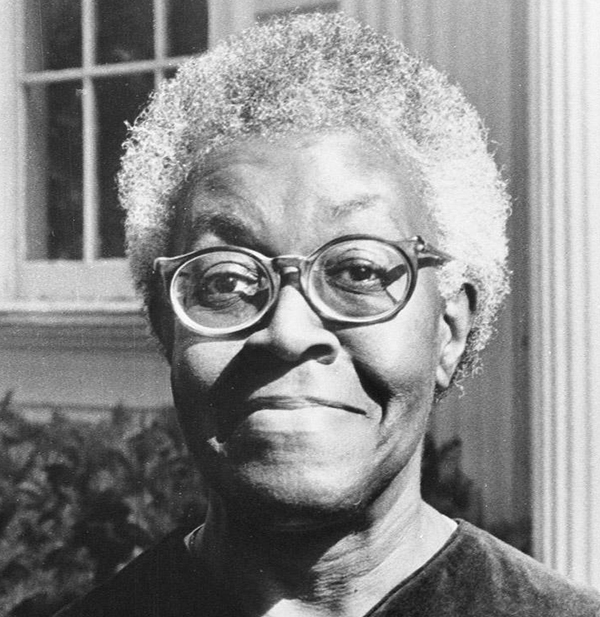

Finding Howland proved difficult. An Internet search turned up very little, “She had just vanished” said Hughes, except for a Wikipedia page with a picture of a cheerful, red-faced blond woman that wasn’t actually Howland, and an article about a return to Chicago in a local paper. Hughes turned some of the sleuthing over to Laura Preston, the magazine’s assistant editor. They ordered her books from online used-book dealers. Blue in Chicago arrived as a discarded library book. The card in the back showing it was popular, being checked out at least once a month for several years.

Preston went down into an Internet rabbit hole. She read some of Howland’s writing and was amazed she had never heard of her before. “I was shocked it hadn’t been anthologized or taught in workshops. It was just really good writing. We spent about three weeks looking for her and started to think she had passed away. She was really tricky to find. We knew she was an alum of the University of Chicago. We learned she taught there in the 1990s with the Committee for Social Thought, but there was no address or email on file. We discovered she’d been to the Yaddo writing colony twice, we learned about the prizes she won, the MacArthur, the Guggenheim, and an NEA grant. We went through all these different channels. No one knew how to find her,” explained Preston, adding that a Yaddo administrator told her that, “‘She’s on our list of the lost.’” Finally, Hughes came across an obituary for Howland’s mother. It listed the surviving family members including the names of Howland’s two sons. One of them, Jacob Howland, Hughes discovered, was Professor of Philosophy at the University of Tulsa.

He responded to an email: Yes, Bette was his mother. Unfortunately, she had had a car accident several years earlier, and for some time had been suffering from dementia. She wouldn’t be able to talk to her. But, Jacob did have some unpublished work of his mother’s, and something else to share with A Public Space, a safety deposit box full of letters from 1961-1990, written to his mother from Saul Bellow. “…Brigid,” he explained, “is the reason we found the letters. My wife and I started looking through Bette’s papers for unpublished material, and that’s when we ran across the letters.”

The letters are part of a portfolio on Howland in the new issue of A Public Space. In the October issue of Commentary magazine, where his mother had also published some work, Jacob explored the relationship between Bellow and his mother: “Bellow was a literary father to Bette (she was 24 and he was nearing 50 when they met at a writer’s conference on Staten Island in the summer of 1961) and an occasional lover. He mentored her and helped nurse her through a defining illness; she ruthlessly critiqued his manuscripts and dispensed cherished praise,” he writes.

“You get an oblique portrait of her because you are not getting what she has to say,” explained Preston, who transcribed the letters for print. “You have to fill in some of the gaps. Bellow is charming, over-the-top, and melodramatic. They are all entertaining to read.”

It is also clear that Bellow believed in her talent deeply. Even while she was in the hospital after her suicide attempt he tried to rally her and encouraged her to write her way out of her depression. He says in one letter: “As for writing (your writing) I think you ought to write, in bed, and make use of your unhappiness. I do it. Many do. One should cook and eat one’s misery. Chain it like a dog. Harness it like Niagara Falls to generate light and supply voltage for electric chairs.”

And Howland did harness her misery and convert it into electricity for W-3. On her decision to take the pills she writes, “I wanted to abandon all this personal history--its darkness and secrecy, its private grievances, its well-licked sorrows and prides--to thrust it from me like a manhole cover.”

In the portfolio, through her stories, an essay, and the letters, a portrait of the writer begins to emerge, but questions remain. What happened to a career that held such talent and promise? Howland was nomadic and often lived in isolation. Why did she retreat from what she had earned for herself? What role has the literary community played in allowing her work to fall from memory? Her son Jacob thinks the MacArthur is part of the answer.

The MacArthur turned into an albatross. “…I think the award may have sapped her confidence,” said Jacob. “If people don’t expect great things from you, it’s easier to please them. But people expect great things from a writer who has won the MacArthur.”

Reginald Gibbons, who as the editor of TriQuarterly in the 1990s published her novella Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage--the piece Jacob thinks is her best work: “I managed to get that story from her by asking again and again for something. She seemed so tentative about her work.”

Hughes isn’t finished with Howland. There are her letters to Bellow, which she has discovered in Bellow’s archive at the University of Chicago, and when she is able to access them, she hopes to be able to run Howland’s side of the correspondence in the magazine. She is still trying to track down a story she published called “The Lost Daughter.” “There is a lot more I want to understand,” said Hughes. “Why has she been forgotten?”

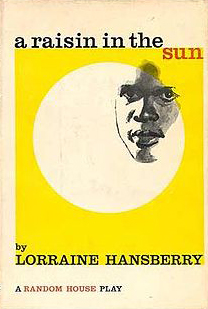

The issue of A Public Space did turn into one dedicated to pieces by other underrecognized women writers including Martha King, Kathleen Collins, Rosalyn Drexler, and Friederike Mayröcker. Between these women, Hughes sees not just a commonality in their obscurity, but in the space they shared in their lives. For example, Howland’s first story was published in Bellow’s magazine, Noble Savage, along with a Lucia Berlin story. Berlin, another recently rediscovered writer, has been brought back into print with wide acclaim. In A Public Space, Martha King writes about being at Lucia Berlin’s memorial service. Only a handful of people are there. It is a quiet overlapping dance of underappreciated writers.

A.N. Devers

As I was sitting at my desk researching this piece, A Public Space managing editor, Lena Valencia, announced to her co-editors, “I found a Rosalyn Drexler book on the discount cart at Unnameable Books this weekend.” They all cheered and passed it around.

The following letter, from Saul Bellow to Bette Howland, is reprinted in full with permission of Mr. Bellow’s estate. A larger selection of letters from Mr. Bellow to Ms. Howland is featured in A Public Space.

JULY 24, 1968

Dear Bette–

I started to write, then decided to wait until Peltz’s visit, just concluded. The message he transmitted was authentic. We are friends, and no friend would let you lose the year--not this year. I thought it unkind--horrible--that your husband would not take the boys in August but tried to bargain with you, taking advantage of your illness.

Peltz’s report on the state of your health was less pessimistic than yours. Of course as a believer in the triumph of vitality, looking on the bright side, Peltz is not a trustworthy informant. But I hope he is right, and that you won’t be an invalid-prisoner for a whole year. Anyway, you must have your own place. That I’m sure can be worked out--in Chicago, if necessary. You don’t really mind Chicago too much, apart from weather conditions.

My plans (Oh God, my plans!) for coming to Chicago are in embryo--perhaps not even conceived--but I believe I will come on about Aug. 5th after visiting little Daniel on the Vineyard. As for writing (your writing) I think you ought to write, in bed, and make use of your unhappiness. I do it. Many do. One should cook and eat one’s misery. Chain it like a dog. Harness it like Niagara Falls to generate light and supply voltage for electric chairs.

Love,

Saul

read less