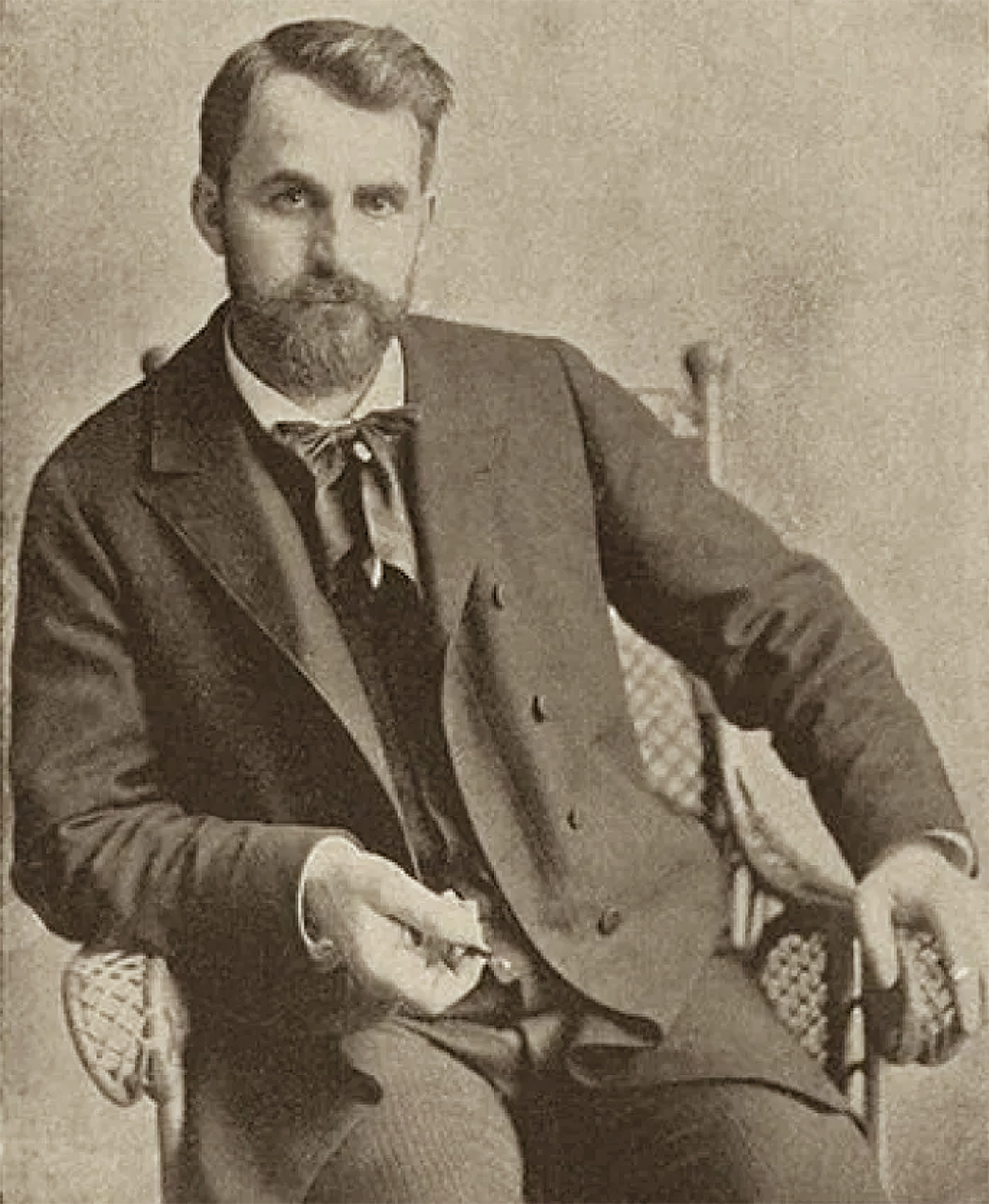

Hamlin Garland’s story is a major challenge for anyone seeking to capture his life and times in anything less than a full-blown biography. This is in part because his life consists of many distinct phases corresponding to the numerous places he lived… for example, boyhood years in Wisconsin, Iowa, and South Dakota before career years in Boston, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. The irony here is an author known primarily for stories set in rural locations working from four of our country’s largest cities.

Hamlin Garland’s induction into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame brings a welcome focus to this essay. As an Iowa native, it’s a joy to know that Garland now joins Edna Ferber (2013) and Floyd Dell (2015), two younger contemporaries also with Iowa backgrounds. And it would undoubtedly amuse Garland to be inducted into the same Hall as his friend Henry Blake Fuller (2017). If afterlives include conversation, these two are now discussing how Fuller’s induction preceded Garland’s by several years.

I have long contended most evaluations of Garland have overlooked the importance of his formative years in North Iowa, briefly in Burr Oak Township, Winneshiek County, 25 miles west of the Mississippi River, then eleven years in Burr Oak Township, Mitchell County, Iowa. I’m pleased this assessment seems to be changing, as more recent evaluations have noted Garland’s Mitchell County years, from age ten to twenty-one, which furnished the author with material he drew on throughout his distinguished career.

Your Chicago focus now prompts my reevaluation of the time Garland spent living near Lake Michigan. It’s evident that Garland’s Chicago period was similarly vital to the author, both as a writer and as an individual. In the following paragraphs, I seek to explain and interpret the importance of his Chicago years.

Garland moved from Boston to Chicago in 1893, motivated by both personal and professional reasons. Foremost, he sought to be closer to his aging parents, who he helped moved to West Salem, Wisconsin, a community he could reach via an overnight train from Chicago. Garland was also responding to the distinct professional lure of Chicago. At the conclusion of the Columbian Exposition, there was a fresh dynamism in the city, a stimulating atmosphere, a readiness for the next century, which Garland hoped to play a part in.

Garland arrived in Chicago in his early 30s, a time of increased recognition as an author demonstrating considerable promise. He was soon invited to give a “salon lecture” at the home of a socially prominent hostess, where he spoke on the topic of “Impressionism in Art,” a movement then emerging in the U.S. art world. Garland had already done a deep dive on this particular topic while still living in Boston.

This gathering was a milepost in Garland’s life, for at the conclusion of his remarks, an attendee approached and introduced himself. Lorado Taft was primarily a sculptor but lectured broadly on the arts to groups like the one assembled that evening. Taft was eager to connect with Garland… and vice versa. Nurtured by their mutual admiration, this vital friendship would endure for four decades, until 1936, when Taft died. Importantly, before the turn of the century, in 1899, Garland would marry Lorado Taft’s sister, Zulime.

Writing is generally a lonely profession. Perhaps as an outgrowth of his solitary work, Garland sought camaraderie when he wasn’t placing words on paper. He enjoyed Taft’s companionship and gravitated to Taft’s studio late afternoons. Before long, others joined them, finding a sense of community among like-minded individuals. One of those often stopping by was Henry B. Fuller, then a writer of novels set in Europe. Over the years, Fuller and Garland formed an enduring friendship important to both men, which, like Garland’s relationship with Taft, lasted until Fuller’s passing in 1929.

Shortly after they began spending time together, Garland, Taft, and Fuller formed an organization they called The Little Room. Ostensibly, the group’s purpose was to provide a setting where artists, writers, and intellectuals could socialize, formalizing what these men once found in Taft’s studio. In addition to the three mentioned, members included social reformer Jane Addams, painter Ralph Clarkson, publisher Ralph Fletcher Seymour, poet Harriet Monroe, plus various painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, architects, and others engaged primarily in arts-related professions.

Little Room records from the early 1900s include an emerging proposal to form a separate entity, a men’s organization, initially called The Attic Club, a step that took place in 1907. Two years later, this start-up entity assumed a new name: The Cliff Dwellers Club. More than any other single individual, Hamlin Garland is regarded as the Cliff Dwellers’ founder.

Before traveling further down the path of Garland’s Chicago activities, it’s important to note an entity that came together among largely this same group seeking an escape from city life. In its early days, the Little Room met in different sculptors’ spaces before eventually making a home in artist Ralph Clarkson’s studio, which accommodated these gatherings for three decades. In addition to their regular gathering time, the group would assemble periodically on Saturday afternoons for a potluck “camp supper.”

Striving to sustain this atmosphere, members soon embarked on an effort to find a permanent campground, in this instance, at a location one-hundred miles west of the city. In the late ’90s, efforts to take The Little Room out into the country led to formation of Eagle’s Nest Camp near Oregon, Illinois. Unlike the Cliff Dwellers, where Garland is prime founder and Taft, a founding member, at Eagle’s Nest, Taft is principal founder and Garland, a founding member.

In addition to Taft and Garland, camp charter members included attorney Wallace Heckman, the property owner, artists Ralph Clarkson, Oliver Dennett Grover, and Charles Francis Browne, authors Henry B. Fuller and Horace Spencer Fiske, editor James Spencer Dickerson, architects Allan B. and Irving K. Pond, and composer/organist Clarence Dickinson – trustees dedicated to the pursuit “of the fine arts, literature, and the professions.” Members were responsible for at least two lectures a year, either on the property or in the nearby community, an intentional effort to promote art education. In its early years, camp was an accurate description… basically, city dwellers “roughing it.”

Initially, camp staff consisted of Taft’s sister, Zulime, responsible for managing the site and tending to meals and supplies. Zulime assumed this role having served in a similar capacity at her brother’s studio. She had studied in Europe and was hopeful of becoming an artist, something her brother sought to advance among the talented females affiliated with his studio. At camp, Zulime was soon taking long after-dinner walks with Hamlin Garland, ten years her senior. Garland tells of their courtship in Daughter of the Middle Border, the book that earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 1922.

While devoting a portion of his energies to courting and clubbing, Hamlin Garland was also at work on a novel during his early Chicago years, one partially set in the city, the outline of which began in Boston prior to his arrival. Most critics regard Rose of Dutcher’s Coolly, published in 1895, as Garland’s finest novel, his best work rooted in his Chicago period. It’s evident that Garland draws on his own background for his lead character, both in her early years on a small Wisconsin farm near the Mississippi River and in the life she experienced in Chicago.-

One reason for the book’s quality is time and effort Garland devoted to it. Initially envisioned in 1890 as a short story, the story quickly outgrew its format. Garland wanted what became a full-length novel to carry many of the themes he had advanced throughout his early career: the challenge of being rooted in country life while seeking to thrive in the big city; the ability to tap one’s background for artistic purposes; the opportunity to be measured on the basis of talent rather than gender or station in life.

In titling his books, Garland frequently employed the word “roads” or “trails” descriptive of his characters’ journeys. Accordingly, it’s appropriate to borrow his term “trail-maker” to encompass the many times the author was either first or very early on what would eventually become a well-travelled thoroughfare. Some of Garland’s trailblazing pertains to his literary endeavors; some reflects the broad scope of his interests.

Having mentioned Rose, Garland was not the first male to write a novel from a female’s perspective. But as critics observed, by making his central character a woman, he demonstrated an ability to stretch himself, not only describing Rose’s intellectual growth but also her sexual awakening, something appearing very rarely in literature prior to 1895.

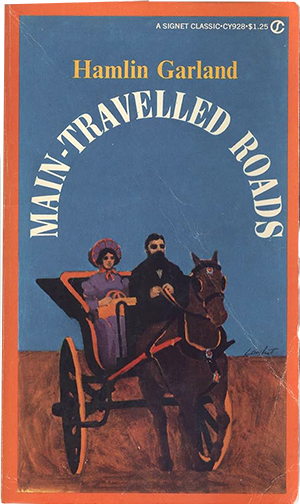

Four years before Rose, Main-Travelled Roads made Garland an informal spokesperson for 19th century agrarian society. While other writers brought a rural background to their works, Garland was the first author to capture the hardships, the disappointments, and the isolation of farm life. As one literary historian noted, before Garland, stories about the frontier were drawn from the victors’ perspective; Garland’s stories came from the victims’ perspective, a significant difference.

Garland is also due considerable credit for pioneering work in developing one of America’s most distinctive contributions to world literature: the western. His western novel, The Eagle’s Heart, (1900), featuring a cowboy hero, is as much a quintessential western as Owen Wister’s The Virginian, a book more well-known. Garland’s novel, however, preceded Wister’s by two years.

The road traveled by Hamlin Garland was long and winding. Throughout his Chicago years, the author encountered diverse frontiers and repeatedly set out to blaze new trails. Garland’s pioneering was accomplished first with a plow, then, ultimately, with his pen. For his ability to bring a fresh perspective to American literature, Hamlin Garland is a significant addition to the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

Kurtis L. Meyer

read less