Great writing is writing that can be reread with increased pleasure and clearer understanding. Some simple truths are almost always rejected, anathema to the modern mind. One of these is that a good book can be written on any subject. And that a bad book can be written on any subject, too. A great writer is not merely great himself; he makes his readers great. Subjects are not good or bad, the writing makes them so.

—Gene Wolfe

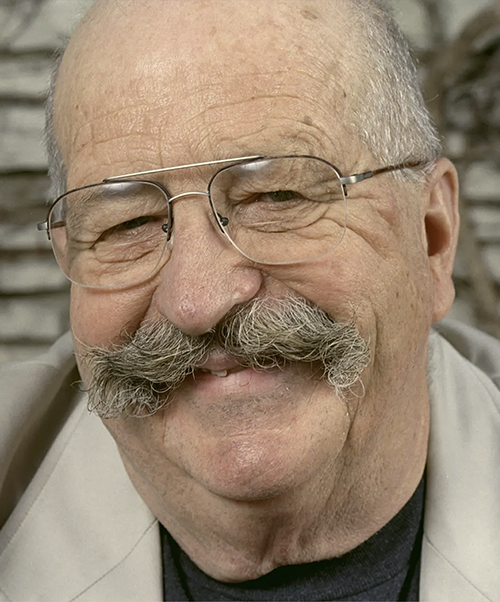

When people who love literature talk about Gene Wolfe, five declarations almost always follow:

- Gene is one of the greatest science fiction writers of all time.

- Gene is a writer loved by writers.

- A Gene Wolfe story can’t just be read once, because the experience improves with each reread.

- Gene Wolfe’s narrators are sometimes unreliable and challenge the reader.

- Gene’s stories are full of puzzles, allusions, and archaic diction.

What people don’t often say is that Gene Wolfe is a Chicago writer, a brilliant literary stylist whose work bridges his contemporaries, the New Wave speculative writers and postmodern magic realists.

Although he didn’t begin to publish stories until he was 34 years old and his first novel when he was 39, Gene Wolfe published more than 30 novels and more than 200 short stories before dying at the age of 87 on April 14, 2019. Much of that work is difficult to classify. Gene traverses genres, from science fiction to noir to mystery to ghost story to epistolary novel, digging deep into themes that recur and evolve: the origin of the Universe, the nature of good and evil, what it means to be a moral person in a morally corrupt world, the truth of memory and perception.

Gene Rodman Wolfe was born on May 7, 1931 in Brooklyn, New York. His father, Roy, was a traveling salesman, and so the family moved around when Gene was young, first to Peoria, Illinois; next to Massachusetts and Ohio; eventually on to Des Moines, Dallas, and Houston. In grammar school, the introverted Gene escaped into comics, model planes, and stories by Edgar Allan Poe, L. Frank Baum, and Rudyard Kipling. He discovered science fiction in The Pocket Book of Science Fiction, a pulp paperback shared with him by his mother, who was also a voracious reader. Theodore Sturgeon’s story “The Microcosmic God” opened a new world to Gene, who went on to spend many afternoons in junior high reading pulps behind the candy case at the pharmacy.

In high school, he had an English teacher who encouraged his writing, but Gene chose to pursue his degree in engineering at Texas A&M, where he wrote a few stories for its literary journal before deciding to drop out. He was drafted into the Army and served in Korea as a combat engineer from March 1953 to May 1954. He frequently wrote home to his mother, Mary “Fanny” Olivia Ayers Wolfe; the collection of those letters was later published as a book, Letters Home, in 1991.

Reading Gene’s war letters, full of playful and imaginative prose, reveals a blueprint for what was to come in his fiction. There were times when he was unapologetically

honest and relayed vivid details of the soldier’s life. Other times he took the tone of a correspondent: “G. Rodman Wolfe, your far-eastern correspondent with the 7th Div. in Korea,” or Wally Balloo of the “Asia News Letter,” no doubt using humor to assuage his parents’ fears. He spent one letter explaining a theory of how “this planet has been periodically, at least, visited by the inhabitants of other worlds” who, when seen, have mistakenly been identified as “witches, demons, fauns, werewolves, ghosts” etc. There were also painful letters, where we can read between the lines to get a sense for things that Gene chose not to tell his mother. Already, he was figuring out that certain information is better omitted, and certain stories needed to be told by different narrators in different ways.

After coming home from the Army, Gene attended the University of Houston on the GI Bill and earned his degree in mechanical engineering. He married his childhood friend from Peoria, Rosemary Dietsch, in 1956, and also converted to Catholicism, which shaped much of his life and writing. Gene then went to work in research and development for Procter and Gamble in Ohio, where he helped to develop the production equipment that made Pringles.

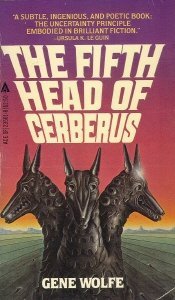

With the publication of his first story, “The Dead Man,” in Sir in 1965, Gene’s literary career began in earnest. Hoping to bring in extra money to help his wife and children, Gene began to write and publish more, assisted by the mentorship of editor and critic Damon Knight. The critical acclaim he received for The Fifth Head of

Cerberus in 1972 set him apart as an eloquent and sophisticated prose stylist. Knight invited him to participate in a prestigious writing retreat in Milford, Pennsylvania, where he workshopped his writing along with Ursula K. Le Guin, Anne McCaffrey, and Frederik Pohl.

At that time, Gene moved his family back to Illinois, taking a job in the Chicago suburb of Barrington as a senior editor for the trade journal Plant Engineering. He worked there from 1972 to 1984 as robot editor, screws editor, letters-to-the-editor editor, glue editor, welding editor, and comics editor. While he and Rosemary raised

their four children, Gene would wake up early every day to write for an hour before work, as well as on the weekends. Finally after the success of The Book of the New Sun, Gene was able to quit his editor job to make a living as a full-time writer.

Gene Wolfe’s body of work is difficult to classify because so much of it exists at the intersection of what seem to be opposites. He was influenced by the classics and the Sunday Comics, novels of realism and the pulps, engineering manuals and religious texts. Gene’s dialogue might be conversational but is also peppered

with antiquated diction. His prose style could be both technically complicated and elegantly lyrical. Comfortably melding science fiction paradigms, the scientific method, and mythological archetypes, Gene invited his readers to occupy that same space—to suspend disbelief and step into the intersection of opposing ideas working together to get at a more accurate truth. That intersectionality is the context for Gene’s legacy as a Chicago writer. In the middle of the country, centered between the coasts with their respective styles and sensibilities, Chicago is a city “in between,” an urban metropolis with small town sensibilities, a city of skyscrapers and green spaces.

Chicago is also a city of borders: the enormity of Lake Michigan to the East, the rural landscape to the south and west, and within, neighborhoods defined by ethnic and racial borders as well. The Midwest, and Chicago in particular, evokes liminal spaces—a rich ethnic diversity and spiritual undercurrent brought to the city by waves of migrants and immigrants in the 20th century. Chicago writers like Stuart Dybek and Harry Mark Petrakis drew from their heritages to incorporate speculative elements into their lyric, descriptive prose, as they wrote about dwelling in those unique spaces. Like Dybek, Gene Wolfe’s writing is character-driven with carefully crafted sentences and symbolism and language choices that serve the story. Like Dybek, his writing also deals with themes of memory, time, and transformation. This can been seen in Gene’s beautiful 1975 novel Peace, where he presents us with a phantasmagorical Midwestern memoir that transforms as you read and reveals even more upon rereading.

His 1984 novel Free Live Free is set in a condemned building during a Chicago winter. Rich in detail and description, Free Live Free is a story about time and space, contradictions and border crossings. Sometimes those borders are actual places in the urban landscape, sometimes they are temporal or fantastic. At the heart of it, of course, there is a mystery, a question, a puzzle. Because that wasn’t just Gene’s technique. It was his point.

For six decades, Gene explored humanity’s relationship with the unknown and unknowable, be that outer space, the past or the future, the human mind or the human heart. The central truth of his stories is one of the best gifts that fiction, and especially science fiction, have to offer us: that people can change, the future can change, and the possibility of change means that there is hope.

—Valya Dudycz Lupescu

read less