This song has no tune. You cannot hum it.

This song has no words. You cannot sing it.

This song everybody knows, nobody knows.

It is in a pattern of brown faces at the Wabash Y.M.C.A., a 35th Street gambling place, a Parkway theatre—you get it or you don’t

It is a melody of everything and nothing

from “Chicago’s Congo”

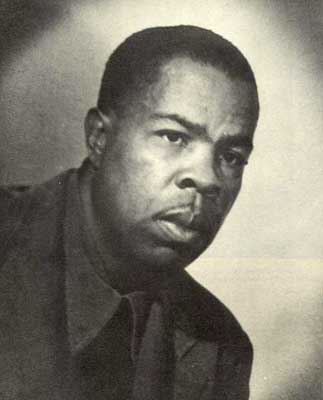

Frank Marshall Davis distinguished himself as a top poet and journalist during the 1930s and 40s, and produced a considerable body of work that influenced generations of poets. He worked at a series of newspapers, including as executive editor of the labor weekly Chicago Star, which he co-founded. He also wrote fiction and published a classic essay in Negro Digest’s 1944 series “My Most Humiliating Jim Crow Experience.” He was a core member of the group of Black authors on the Federal Writers’ Project in Chicago who formed the South Side Writers’ Group to hone what would become, according to scholar Andrew Peart in his Chicago Literary Hall of Fame nomination of Davis, “a distinctive style of 1940s black literature in Chicago, blending social realism, race consciousness, and protest.”

Peart also said that, “Marshall’s poetry collections Black Man’s Verse (1935), I Am the American Negro (1937), and 47th Street: Poems (1948) rank alongside Margaret Walker’s For My People (1942) and Gwendolyn Brooks’s A Street in Bronzeville (1945) as Chicago’s cornerstones of black poetic modernism.”

Davis was born and raised in racist Arkansas City, Kansas, where, according to John Edgar Tidwell, White children nearly killed Davis because they wanted to experience a lynching. He attended Friends University in Wichita before transferring to Kansas State Agricultural College’s school of journalism, where Davis first was exposed to writing free verse.

In 1927, Davis moved to Chicago, where he wrote articles and short stories for magazines and newspapers. Davis left Chicago three years later to take an editorship in Atlanta, but returned in 1935, the year his first book was published. Between 1935 and 1947, Davis was Executive Editor for the Associated Negro Press in Chicago. He also formed a photography club, participated in the League of American Writers, and was active in politics.

Davis’s insistent exploration of Black life resulted in a great number of classic poems that protested racial inequality and promoted Black pride. He displayed an unabashed self-awareness in many poems, but most of all in “Frank Marshall Davis: Writer.”

It went, “When I wrote / I dipped my pen / In the crazy heart / Of mad America.”

Biographer Kathryn Waddell Takara notes that Davis belonged to the New Negros coming out of the Negro Renaissance of the 1920s, a category of writers exhibiting pride in their race. She writes that he was “more than a polemicist. Davis was also a humanist, a complex yet idealistic individual who defied convention yet maintained a utopian perspective throughout his long life.”

Indeed, Marshall gained much acclaim for his poetic vision, starting with his inaugural publication. Harriet Monroe wrote in Poetry that Marshall was “a poet of authentic inspiration, who belongs not only among the best of his race, but who need not lean upon his race for recognition as an impassioned singer with something to say.”

Black Man’s Verse combined Davis’s interest in jazz and free verse with blunt criticism of racial oppression. Sterling A. Brown, considered a quintessential “blues poet,” stated that Davis “at his best is bitterly realistic.” Tidwell argued that Davis ranked with Langston Hughes as a primary precursor to the 1960s “jazz poetry.” The section of the book called, “Ebony under Granite,” tells the stories of Black people buried in a cemetery; that led many to compare the collection to Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology.

I Am the American Negro, Davis’s second book, continued in its harsh critique of racism, in particular Jim Crow laws.

Davis’s finest collection, 47th Street, was published in 1948, the year Davis’s vacation to Honolulu, Hawaii, turned into a permanent relocation. 47th Street chronicles the diverse South Side culture and people. His exploration of a myriad of races signaled a move toward concern with class as much as color.

Richard Guzman writes that “Davis’ poetry is notable not only for its social engagement, especially in the fight against racism, but also for its fluent, lyrical language and stunning imagery.” Guzman notes that in addition to Davis’s short lyrics, he also produced long-form poetry that was often arranged as mini-dramas.

This experimentation with form, along with Davis’s unique and powerful messages, inspired a great number of writers, as well as future president Barrack Obama, who famously wrote about his mentor in his memoir.

“An early poet that inspired me was without doubt or hesitation Frank Marshall Davis,” said poet Haki Madhubuti. “He was a poet I would go back to because he was able to steal an idea with such a few lines. There is irony in his poetry, and he has the ability to cauterize an idea. For me, Frank Marshall Davis set the example for a conscientious serious writer who cared for Black people deeply. He told us about our world.”

Davis stayed in Hawaii the remainder of his life. He wrote a weekly newspaper column, ran a small wholesale paper business, and raised five children. The Black Arts Movement rediscovered Davis’s work after a period in which his popularity had declined. In 1978, Davis published his final poetry collection, Awakening, and Other Poems.

Black Moods: Collected Poems (2002) and Livin’ the Blues: Memories of a Black Journalist and Poet (1992) were published posthumously.

read less