And we walked and walked and walked—walking through the great Trumbull Park, Buggy walking to Helen, Harry walking to his wife Margaret, walking to all our friends there. Walking.

—from Frank London Brown’s Trumbull Park

Shortly before the release of his seminal 1959 novel, Trumbull Park, Frank London Brown penned a profile of jazz great Thelonious Monk for Downbeat. “Thelonious Sphere Monk finally has been discovered,” he wrote, recognizing in Monk a rare creative genius who would spend the next thirty years transforming jazz, years Brown would not live to see though he was a full decade younger. Just four years later, at 34, he succumbed to leukemia, and though his contributions to literature and the Civil Rights movement…

read moreAnd we walked and walked and walked—walking through the great Trumbull Park, Buggy walking to Helen, Harry walking to his wife Margaret, walking to all our friends there. Walking.

—from Frank London Brown’s Trumbull Park

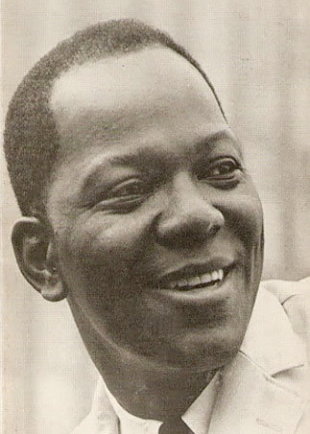

Shortly before the release of his seminal 1959 novel, Trumbull Park, Frank London Brown penned a profile of jazz great Thelonious Monk for Downbeat. “Thelonious Sphere Monk finally has been discovered,” he wrote, recognizing in Monk a rare creative genius who would spend the next thirty years transforming jazz, years Brown would not live to see though he was a full decade younger. Just four years later, at 34, he succumbed to leukemia, and though his contributions to literature and the Civil Rights movement were significant, Frank London Brown’s own literary genius would, until recent years, largely fall into obscurity.

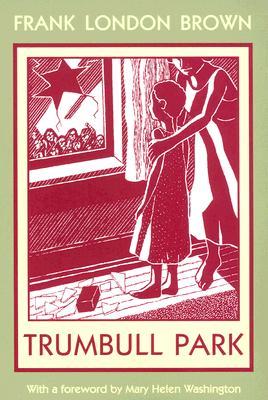

Trumbull Park sold more than 25,000 copies, catapulting the author into short-lived fame and solidifying his place within the Chicago Black Renaissance. Inspired by his family’s tumultuous experience integrating Trumbull Park, a White public housing development at 105th and Yates on the far South Side, the novel dramatizes the terror and eventual empowerment of several Black working-class couples as they endure violent mobs and police indifference, as well as rising tensions within their own ranks.

Unapologetically political and progressive, Frank London Brown was a union organizer and a Civil Rights activist, as well as a writer, muckraker, musician, reporter and editor. He worked numerous jobs to support his growing family and his literary aspirations, endured poverty and racism, as well as constant surveillance by the FBI. Described by scholar Mary Helen Washington as “a handsome and eloquent man,” Brown could talk to anyone, loved jazz and the blues, and occasionally sang in the clubs. He read his stories aloud at The Jazz Showcase. He joined Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot in New York and cut a 45 of “Let’s Have a Party (Let’s Have a Ball)” with Lil Armstrong, a song his daughter Debra Thompson-Brown remembers singing with her father on weekends when the house was filled with the sounds of Charlie “Bird” Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Dizzy Gillespie.

Brown’s love of music and innovation weaves through much of his work. Richard Guzman heralds his acclaimed short story “MacDougal,” which features a White jazz musician on Chicago’s 58th Street, as one that explores “the possibilities that people could relate and empathize across the terrible racial boundaries he [Brown] spent his short life not only writing about, but also trying to help everyone overcome in daily life.” And Trumbull Park is a cacophony of noise, from the city, from the angry White crowds that surround the housing development. In a penultimate scene of resistance and communal power, the main characters sing a refrain from a Joe Williams blues tune as they march toward the mob.

Born in Kanas City, Frank London Brown moved to Chicago when he was twelve and was educated at DuSable High School and Roosevelt University. He attended Kent School of Law for a time and earned an MA in Social Science from the University of Chicago. He was Director of the Union Research Center of the University of Chicago and a candidate for a doctorate from the prestigious Committee on Social Thought. As a journalist and editor, he published countless articles in the Chicago Sun-Times, Ebony, The Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Defender, the Chicago Review, Negro Digest, and other periodicals. He’s known for his unflinching coverage of the murder of Chicago teen Emmett Till in Mississippi, and he wrote features on a number of important artists, including gospel singer Mahalia Jackson.

In Brown’s work is a unique knowledge of the complexities of humanity and of Chicago, honed through the many people he met working various jobs and recruiting for the AFL-CIO and the UPWA. Debra E. Brown-Thompson, one of his three daughters, recalls accompanying her father on a union canvassing trip in an unfamiliar neighborhood. “We walked for blocks and blocks, must have knocked on about 30 doors,” she said. “‘Hello, I'm Frank Brown,’ he’d say. Daddy had a way of talking to people that made them feel they had known him for years.” She had nearly memorized his speech when they walked up a decrepit back staircase and her father asked if she wanted to try. “The door opened and this big, burly, White man with a big belly, gray pants, and white shirt pushed open the screen door. ‘What da' ya' want?’ he said in gruff, bullying voice.” Her father waited for her to speak. What happened next is hazy for Brown-Thompson, but she doesn’t think it ended well. Still “I felt so brave and proud of myself! I knew then I could confront anyone, anything, at any time. I had just asked a big ole' White man to join my Daddy's Union. It didn't even matter what he said.”

Thompson-Brown recalls how her father would take the family on car rides to “follow the sun,” as he would say, down 95th Street. In summer, they would stop at the Rainbow Cone Ice Cream Shop on 95th and Ashland for sherbet. In winter after the first snow, they’d drive to the Midway on 55th Street near the University of Chicago. “He would say, ‘Okay! Look at the snow. There are no footprints! Let's make our mark on the world!’” They would run up and down the Midway making footprints in the snow. He encouraged his daughters and his community to use their voices and to leave their marks.

Gwendolyn Brooks eulogized Brown in a poem after his death, and over the years his Chicago community worked to keep his memory alive. In 1969, Path Press, a venture Brown himself once envisioned with Herman C. Gilbert and Gus Savage, published his posthumous novel The Mythmakers. Nonetheless Brown’s legacy languished for a time. While Trumbull Park was admired by the likes of Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks and Sterling Stuckey, several prominent critics minimized its importance, either by only seeing Brown in comparison to Richard Wright, or by criticizing him for not depicting, as R.L. Duffus of the New York Times complained, the “white people of Trumbull Park” and their “fears and frustrations.“

In the 1990s scholars began to re-examine Brown’s work and his place in literary history. In 2005, Northeastern University Press republished Trumbull Park with a foreword by Mary Helen Washington. His work has been anthologized in numerous anthologies and taught in college courses. Over the past two decades interest in his life and books continues to grow. As Brown once proclaimed of his friend Thelonious Monk, we finally can say of him: More man than myth, Frank London Brown has emerged from the shadows.

—Rachel Swearingen

read less