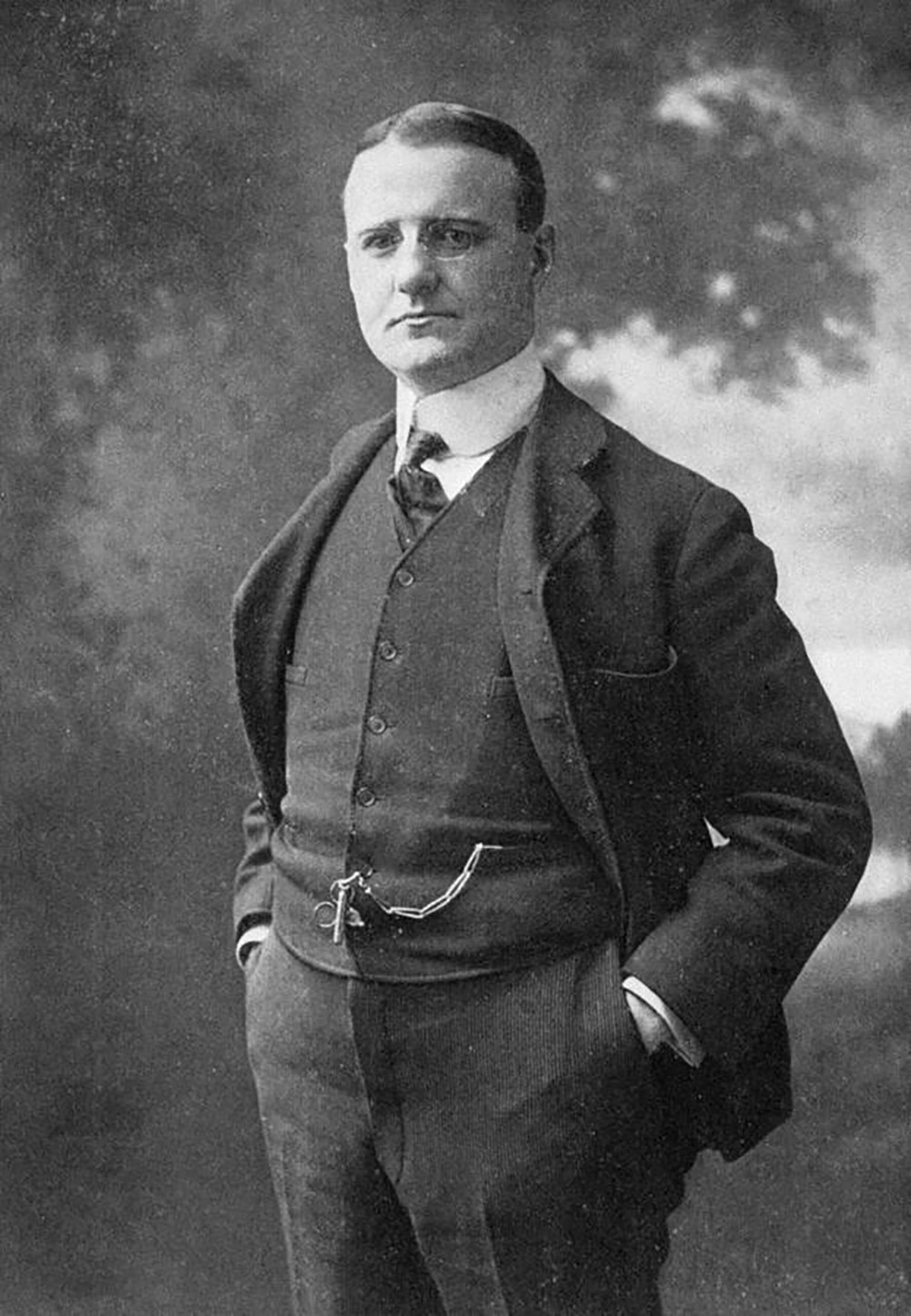

He was one of the most famous people in the world. At the peak of his popularity, Finley Peter Dunne was considered one of the great American humorists of his day, comparable to Mark Twain. Dunne was read by most everyone from the common man and woman on the street up to the president of the United States.

In this day of social media and artificial intelligence--not to mention short attention spans--it may be hard to imagine that one literary figure could wield such cultural influence, but Dunne was no ordinary journalist. Dunne was part of a long and rich Chicago tradition of literary journalists, ranging from George Ade and Eugene Field to Ben Hecht and Mike Royko, who combined exquisite prose with biting wit. Dunne’s career was distinctive for another reason. It intertwined three different aspects of American popular culture: Irish immigration, journalism, and saloons.

Peter Dunne was born in Chicago on July 10, 1867, to Peter Dunne and Ellen Finley, both Irish immigrants, and was raised in St. Patrick’s parish on the city’s Near West Side. His father owned a small lumberyard, while his relatives were active in Democratic ward politics; they also included a number of prominent Chicago priests. After graduating from West Division High School, young Pete--he added his mother’s maiden name Finley later--entered the newspaper business at the tender age of 16 as a copy boy at the Chicago Telegram before being promoted to police reporter. Like other journalists around town, he

worked at other newspapers (and there were plenty of them including the Chicago Daily News), under various beats until, in 1892, he joined the staff of the Chicago Evening Post as an editorial page editor.

It was at the Post where Dunne truly came into his own. Given that booze and writing have always been big parts of the Chicago literary scene it may not be surprising that Dunne decided to combine the two “ingredients” into one singular creation, Martin Dooley. And in perhaps his boldest move, he allowed his character to speak in Irish dialect. Literary historian Charles Fanning called Martin Dooley, or Mr. Dooley, as he was known, the first dialect voice of genius in American literature.

Mr. Dooley dispensed his wisdom while offering ample pours to his workingclass customers along Archer Avenue (Archey Road to him) in the Bridgeport neighborhood. Mr. Dooley was not only a sage and street corner philosopher he was also a survivor of the Great Irish Famine. He was especially known for his acerbic commentary on events of the day, particularly the dubious behavior of politicians.

Mr. Dooley was based on an actual bartender, Jim McGarry, who owned a bar in downtown Chicago and was famous in his own day for displaying equal measures of warmth and wisdom as well as for his gregarious nature. Among the customers who patronized his saloon was a young newspaperman by the

name of Finley Peter Dunne. Dunne loved the ambiance of the bar but most of all he loved McGarry’s sparkling personality and his gift of the gab. Before long, Dunne began writing McGarry’s words down on paper.

Given that the saloon was located at the crossroads where politics and culture came together, McGarry’s also happened to be a favorite gathering spot for politicians, judges, actors, and other assorted denizens of the city. McGarry epitomized the nineteenth century ideal of the bartender: he was everybody’s best friend but he also knew when to keep his mouth shut. (As saloon culture historian Bill Savage once said, “Bars are where people tell each other secrets.”) Significantly, Dunne moved the setting of the tavern from the Loop to Bridgeport, then a predominantly Irish neighborhood on the South Side.

Bartenders were respected figures in the community. They were looked up to. Reflecting his status, Dunne made sure Mr. Dooley dressed the part of the upstanding citizen. In a famous drawing of him, the barkeep is attired in black trousers accompanied by a white shirt worn under a black vest accentuated with a bowtie.

From 1893 to 1898, Dunne’s weekly columns created a fully rounded picture of Irish American working-class life. His portraits of laborers, streetcar drivers, and mill workers, among other occupations, contain memorable moments of dignity and depth. Satirist, social critic, and all-around thinker, Mr. Dooley was an immensely popular character.

Readers identified with Mr. Dooley’s resourcefulness, his quick wit, and his commonsense approach toward life. Through Mr. Dooley, Dunne examined the customs, habits, and attitudes of a working-class Chicago neighborhood and explored other themes too—the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, the plight of the immigrant, the fight for Irish independence, the struggle of the mostly Catholic Irish to attain respectability in then-Protestant America, and the subsequent pains of assimilation. In sum, Dunne wrote hundreds of Dooley pieces, many of which were later published in book form. Most of them were humorous and droll commentaries on contemporary life in Chicago as seen through the eyes of the fictional barkeep. “As a creator of character sketches of Irish immigrants, [Dunne] affirmed that the lives of common people were worthy of serious literary consideration,” wrote Charles Fanning.

In addition to Irish topics, Dunne also addressed other themes in his work, such as social reform, the Pullman strike, and Chicago politics. Dunne’s satirical comments on the Spanish-American War, for example, in 1898 were widely reprinted and ushered in the second phase of his career. In 1900, he moved to New York and his columns became nationally syndicated. By the outbreak of World War I, Dunne reportedly was the most famous columnist in the country.

Decades later, in April 1936, Dunne died in New York of throat cancer. By that time, he had fallen into relative obscurity although his most famous character, Mr. Dooley, was still fondly remembered.

Dunne should also be remembered for another reason. He helped establish one of Chicago’s most distinctively macabre, if short-lived, literary institutions, the Whitechapel Club in 1889. Inspired partly by the Jack the Ripper murders in the Whitechapel neighborhood of London and regulated by the arcane rules of the Clan na Gael, the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Irish republican organization, the Whitechapel Club was a social group of journalists who met in the back room of a saloon on Calhoun Place in so-called Newsboys’ Alley, where they told stories, recited poems, read from works in progress, and typically ended their evening with a round of jovial drinking songs. The unconventional ambiance included skulls and hangman’s nooses that adorned its walls and ceilings. The chief focus of the room, though, was a huge coffin-shaped dining table. Ostensibly, the qualifications for membership were “wit and good fellowship” but the real purpose of their “meetings” was “serious drinking and newspaper gossip.”

Finley Dunne’s Tavern on Lincoln Avenue in Lakeview honors Dunne’s memory and even has a sandwich named after him: Dooley’s Sandwich consists of grilled cheese with a fried egg and bacon or sausage.

June Sawyers

read less