"There was a certain amount of pride placed upon the doubtful distinction of being an “only Negro,” the thing I came to Chicago to escape."

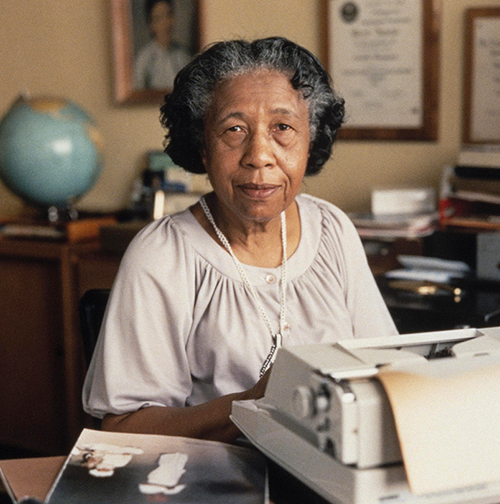

To have seen Era Bell Thompson around the offices at Johnson Publishing Company, you wouldn’t have known she was a big deal. She had her own office, sure, but her constant good cheer, encouragement and humor belied the fact that the granddaughter of former slaves had clawed her way improbably to the elevated status of renowned international journalist. After John H. Johnson hired Thompson as an associate editor of its Negro Digest, she worked as a co-managing editor and visionary for JPC’s leading magazine, Ebony, from 1951-64. Thompson continued to work for Ebony as an international editor from 1964 until her death in 1986.

“She was never one to complain or talk about ‘I had a hard time,’ “ said John Woodford, a staff writer and editor when he worked at JPC in 1965 and then again from 1969 to the late 70s. “She was always extremely positive. She was one to overcome any obstacles and celebrate her abilities to do it. She knew she could write really well, she was a great reporter, and found a place to use her talents.”

Despite all appearances, Thompson was a big deal, more so during Woodford’s second tour, when Johnson Publishing Company had moved north from its converted funeral parlor offices on South Michigan Avenue to its impressive new building in the Loop. In a career that included more than 40 bylined articles and travel to 124 countries on six continents, publication of a memoir and book-length study of Africa, and important interviews with the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr., Thompson quietly sat among the upper echelons of American journalists.

Thompson was 27 years old when she traveled across the Plains and the upper Midwest to witness The Century of Progress in Chicago. This was 1933, the country just barely on the mend from the deepest, most troubling years of the Great Depression. Thompson had been raised first in Des Moines, Iowa, then, Bismarck, Mandan, and Grand Forks, North Dakota, where her father was a farmer, shop keeper and government messenger. After high school, Thompson had seen for the first time a Black newspaper, The Chicago Defender, and soon became a correspondent (she contributed to the “Lights and Shadows” column under the pseudonym Dakota Dick, a cowboy from the Wild West). She’d distinguished herself as a writer for the University of North Dakota campus newspaper and as a college track star. She’d finished her degree at Morningside College (Sioux City, IA), after being forced to leave the University of North Dakota due to illness. The youngest of Stewart and Mary Thompson’s four children and the only girl, Thompson had previously visited Chicago several times. Now, armed with a Bachelor of Arts degree and a few contacts, and with no surviving parents to whom to return, she stayed.

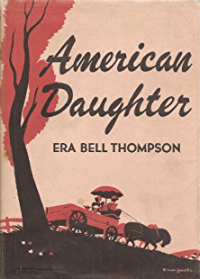

In her memoir, American Daughter, she recounts her entry to Chicago. “My eyes grew big and my heart pounded as the yellow cab weaved in and out of the maelstrom of traffic, turned into Michigan Avenue, and started south. A huge, double-deck bus staggered around a corner, top-heavy and clumsy. I saw a coloured man. Four men in a long black car shot past. Gangsters! They had to be gangsters, Chicago was full of them. A coloured woman, another coloured man. The crowds and the traffic slowly decreased. All around me now were black people, lots and lots of black people, so many black people I stared when I saw a white person.”

She would eventually win a Newberry Library fellowship en route to publication of her memoir, an assistant editorship at Ebony in 1947, promotion to co-managing editor in 1951, and a whole string of successes thereafter. But all of that came many years after she first found boarding at the Young Women’s Christian Association and settled for work as a house cleaner (“...it didn’t help to tell people I was a college graduate.”).

Thompson scrubbed floors, washed windows, ironed, did laundry, starched collars, styled little girls’ hair and potty-trained little boys, cleaned, shined, and tended to various whims in various households. And this counted as the best Thompson could do after relentless, tireless pursuit of gainful employment.

By necessity more than choice, Thompson moved fairly frequently within the confines of Chicago’s Black Belt. That first year, she lived at 56th and South Parkway then moved to Rhodes Avenue until 1935. She stayed with friends for a time at 5239 S. Michigan Ave.

For more than a decade, Thompson labored at temporary jobs while also training for more substantial work. She was a junior clerk for the Chicago Relief Administration, where she started and edited an interoffice newspaper, the Giggle Sheet. Took her civil service exams. Found work at the Illinois Occupational Survey. Then the Works Progress Administration. Did post-graduate studies at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism (1938-40). Was an interviewer with the U.S. and Illinois Employment Survey.

It was in 1945 that Thompson received the Newberry Library fellowship to write her memoir, American Daughter, which was released the following year. American Daughter, which in part told the story of her North Dakota childhood, caught the attention of JPC publisher John Johnson, who hired Thompson.

“I knew she had come from the Plains states, but she didn’t talk much about her experiences in college, except to say that she was isolated from other black people growing up,” said Woodford. “It wasn’t until she came to Chicago that she had a Black community.”

Tenacity and patience, along with a crisp, smart prose style distinguished Thompson as a reporter. Though she traveled as a writer to many foreign lands, she would not commit pen to paper until she’d thoroughly absorbed and learned the local customs and people--their lifestyles, social conventions, even food--a process that often took a full month and a hundred interviews. She based Africa, Land of My Fathers (1954) on her tour of 18 African countries.

Her reputation, based on her published work and public comments, was that of a broker for peace and harmony among all people, including men and women, as well as Black and white. This in a time of enormous division. In fact, she closed her memoir with the lines, “The chasm is growing narrower. When it does, my feet will rest on a united America.” Though Thompson indeed saw the potential for racial and gender equality, she observed and understood society’s injustices and spotlighted them, if sometimes subtly, in her articles.

In the New York Times obituary, Herbert Nipson, then executive editor of Ebony, said, ‘’I worked with her for 30 years--she was an advocate of women’s lib long before it became popular. She did stories in Africa, India, Australia, South America and various islands in the South Pacific.’’

To be sure, Thompson at times confronted racism and misogyny head on, with an erudition and thoughtfulness that demonstrated more than preached the validity of her views. Thompson’s contribution to Ebony’s special 1965 issue, “The White Problem in America,” was an essay entitled, “Some of my best friends are white.” In it, she writes, “With the new order of things, the majority race is finding it difficult to alter a life-time of thinking of the Negro as an inferior and start treating him as an equal; to stop confining analogues to one race and start comparing merit with merit. Willie Mays is the highest-paid baseball player in the major leagues, not the best ‘Negro player.’ Leontyne Price is a credit to the world of opera, not just ‘to her race.’ And between the butler and the ambassador, there are thousands of Negroes who will be tomorrow’s neighbor, perhaps tomorrow’s boss.”

Evidence of the force and confidence with which Thompson advocated for herself as well as all women and Black people presented itself in her public life as well as journalism work. She once wrote a complaint letter to the Chicago Tribune after she’d been excluded from a contributors’ banquet. It said, “I am a respectable citizen, a member of the N.A.A.C.P., the Board of Directors of the Chicago Y.W.C.A. and am on a fellowship writing a book—trying to write a story without malice and without bitterness. Sometimes the writing is very hard.”

In 1957, Thompson spent a night in a South African jail in response to being told there were no hotel rooms for Blacks. Among her book credits, Thompson co-edited White on Black (1963). Many of her later essays criticized men’s treatment of women. She often spoke to college and high school groups to encourage people, especially women, to go into journalism.

Thompson’s writing subjects ranged from Edith Sampson to Adlai Stevenson to Joe Louis. Among her wide circle of friends were several she interviewed for print, such as Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes. Thompson established herself as an active and influential member of the community as she settled into a Chicago life that included a treacherous travel and work schedule. In her early Chicago years, Thompson served the YWCA as an editor, senior typist and junior clerk for short stretches; later she sat on its board of directors. She also maintained a close relationship with her local library, serving, for example, on committees in support of Charlemae Hill Rollins’s and Vivian Harsh’s literature forum.

Thompson lived in three primary residences in the last 45 years of her life. She lived at 6246 S. Parkway from January 1941 until November 1955; 3440 S. Cottage Grove (Lake Meadows) from November 1955 until June 1962; and finally at 2851 S. Martin Luther King Dr. (apartment 710 and then 1910) from September 1962 until her death in 1986. She stayed a short while with friends at 9225 S. Michigan when she was in transition between her last two apartments.

She decorated her homes with artifacts acquired during her travels, including African figurines and a zebra hide she’d had tanned, stretched and dried. Thompson maintained many friendships, often cultivated over a long time, both through social activities like dinner parties and robust correspondence. Thompson, due to her Johnson Publishing position, exerted a sphere of influence that included editors, journalists, politicians, scholars, artists, athletes, and all manner of celebrities.

“All her life, she wrote,” said Beverly A. Cook, librarian and archivist of the Chicago Public Library’s Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection. “That was her friend. She wrote in diaries like other little girls would play with their dolls or talk with their friends. It was a survival skill. She never stopped, not until the very end. She was constantly doodling and making notes.”

Morningside College gave Thompson an honorary doctorate degree in 1965 and its Distinguished Alumni Award in 1974. The University of North Dakota awarded Thompson an honorary doctorate degree in 1969 and ten years later renamed its Black Cultural Center in her honor. In 1976, the state gave Thompson its most prestigious honor, the Theodore Roosevelt Rough Rider Award. The Society of Midland Authors bestowed upon Thompson its Patron of Saints Award (1968). She was among 50 black women included in ‘’Women in Courage,’’ a touring photography exhibit that showed during Black History Month at the Chicago Public Library’s Cultural Center in February 1986.

Thompson donated part of her massive collection of papers and ephemera to the Chicago Public Library in 1984, and the rest upon her death. The Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature holds the Era Bell Thompson Papers, 108 boxes taking up almost 100 linear feet that provides primary evidence of Thompson’s personal and professional life. The Harsh archivists continue to process the vast materials, including manuscripts, correspondence, and Johnson Publishing records and photographs.

“She was like the Grand Old Editor,” Woodford said. “She was always praising people for doing a good job. She worked mainly on her own things. Being a Black journalist, she had so many battles to fight…just getting credentials, to insist upon being respected. She had a lot of verve. She was a very hard-working, imaginative reporter, very thorough; also, she was a really strong, vivid writer. By being such an excellent journalist, she gave luster to and enabled those that came after.”

read less