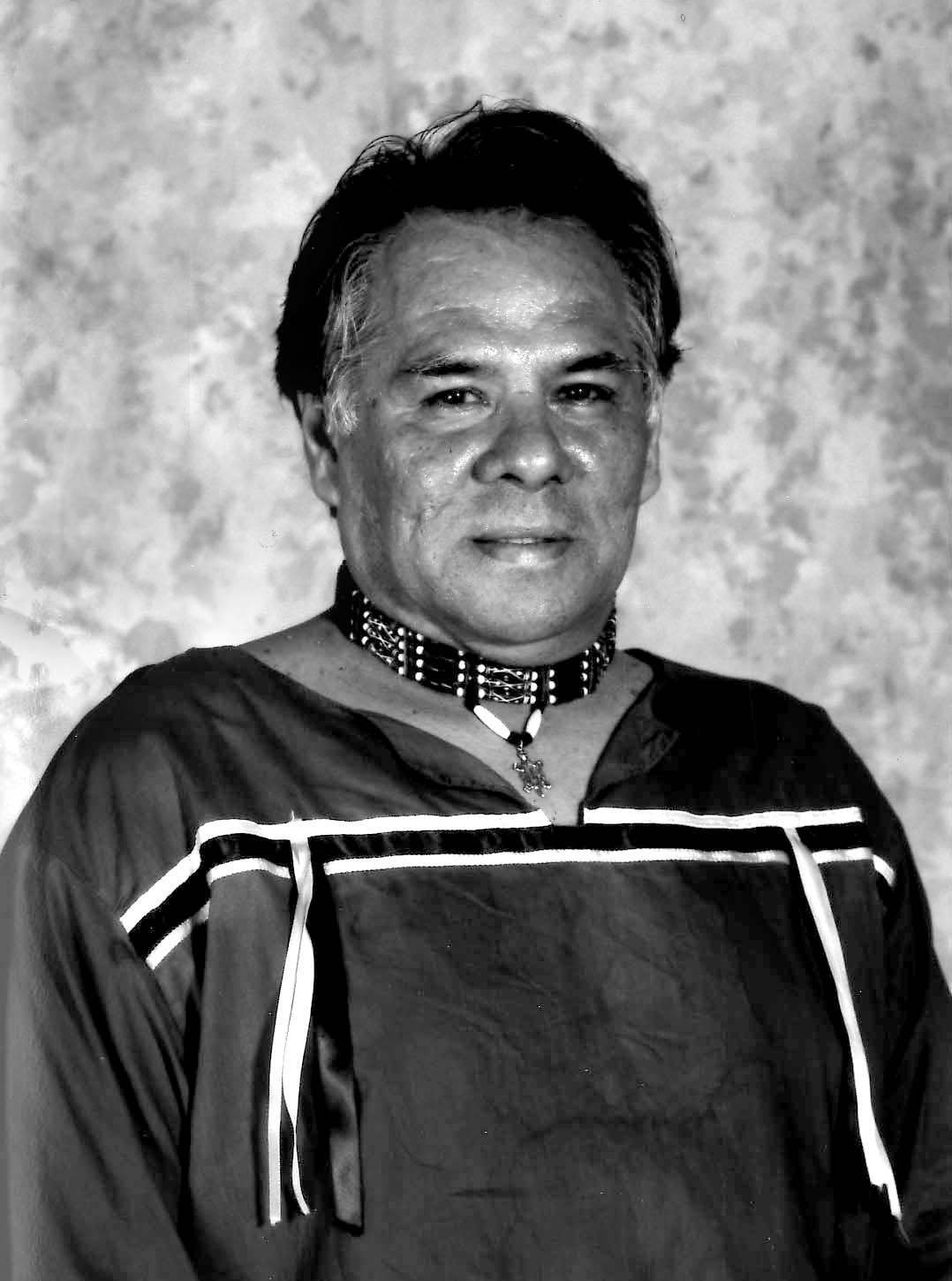

Edmund Donald Two-Rivers Broeffle was born on June 29, 1945 to Nancy Johnson Broeffle. They lived with relatives on the 55,000-square.mile Anishinaabemowin-speaking Ojibwe treaty lands of the Canadian Seine River Reserve in Sapawe, Ontario. He and his siblings grew up guided by their Grandmother Minnie and uncle Robert Johnson. He was raised with traditional activities such as hunting, wild berry-picking and fishing, always surrounded by pine and birch trees; these memories provided him with some comfort while he spent three years in an Ontario reform school. A glimpse into his adolescent adventures learning to communicate with horses and people occurs in the story, “The Horse Barn and Little Lady Jane,” one of 22 short stories in his 1998 book Survivor’s Medicine, published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

A more romantic characterization of his childhood is celebrated in his poem “Indian Land Dancing,” first published in 2003 and later publicly incorporated posthumously as part of an exceptional mural of the same name created by the Chicago Public Art Group in 2009. The poem is located on the south wall at the Foster Avenue and Marine Drive entrance and exit.

In the summer 1961, shortly after turning 16, Two-Rivers traveled nearly 750 miles south from Ontario to live with his older sister in an apartment in Chicago’s economically hard-pressed Uptown area. Since the 1950s, many Native Americans had been encouraged, with Bureau of Indian Affairs assistance, to relocate from rural areas; unfortunately, many became the new urban poor. For many years, Uptown was the population epicenter for American Indians, as well as a port-of-entry for poor whites from southern states and the Appalachians.

Two-Rivers, like many teens, was influenced by the non-conformance times of the rock n’ roll hitch-hiking youth culture of the 1960s; and he was curious to explore the U.S.A. and Mexico. I don’t know if he had read On the Road, by Beatnik rebel writer Jack Kerouac, but Two-Rivers took his own journeys. He traveled to parts of the Midwest, the West Coast and southern border during the dawn of the drug-experimenting Hippie movement.

Upon his return to Chicago, Two-Rivers found factory work near Southeast Side Archer Avenue. He relied on Chicago public transportation to take him from the North Side to work. This fortunately allowed him to study the bus and train passengers and observe close up Chicago’s ethnic neighborhoods. Many of these images are reflected in the dialogue of his plays, fiction and poetry.

Trying to survive by his wits, he committed a series of armed robberies and was caught and jailed. Decades later, after becoming an established writer, I asked him why he committed those stick-ups. He candidly said, “It was easy, too easy. I’d just show my pistol and like a magnet, the wallets would appear at my feet. I got addicted to the adrenaline rush, and I did it one too many times and was busted.”

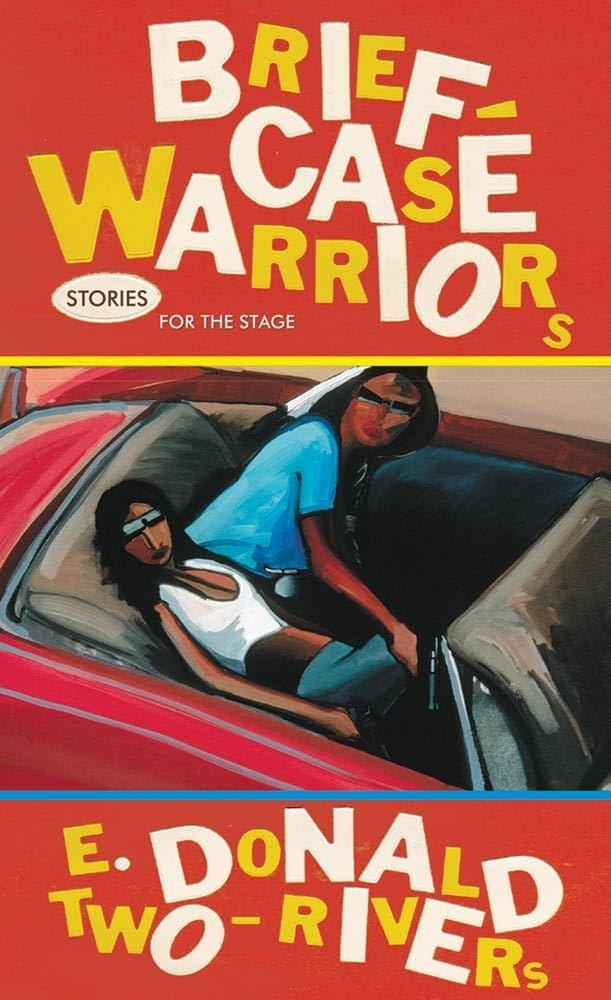

He was sentenced to Cook County Jail where he met Paul Crump, a convicted murderer of a security guard. Crump became a celebrity after he wrote a novel, Burn, Killer, Burn! Two-Rivers learned that Nelson Algren had been an influence on Crump’s desire to write, which sparked him to read Algren’s tales of the “lumpen proletariat street hustlers, day laborers, prostitutes.” Such characters appear in Two-Rivers’s drama collection, Briefcase Warriors, also published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

In the early 1970s, Two-Rivers was nearly 26 and became active in grassroot actions, such as the June 14, 1971 move by members of a Mike Chosa-led group called the Chicago Indian Village that wanted to reclaim land for Native Americans. One of their locations was an abandoned U.S. missile silo situated at Belmont Harbor. This was, in fact, federal land. Many believed Mayor Daley’s repressive cops could not openly move against Indigenous people on federal property. This symbolic action lasted about a month before the activists were evicted. Two-Rivers was inspired by and supported such acts of resistance. It would be 20 years before Two-Rivers and I discussed our mutual connections to that event and other indigenous protests, such as the 1973 Wounded Knee confrontation, the arrest and railroading of AIM activists such as Leonard Peltier, the Wisconsin fishing rights struggle, and protests in the 1980s against Peabody Coal company’s violations of Navaho and Hopi water rights at Black Mesa.

One clear example of Two-Rivers’s activism is found in the rare 1994 poetry anthology SKINS: Drum Beats from City Streets, which he co-edited with professor of anthropology Terry Straus. This was a ground-breaking book of 20 American Indian poets with a Chicago connection, some of which have continued to write and publish, like Mark LaRoque and Mark Turcotte. The anthology’s lead poem, by Two-Rivers, is entitled “Warrior 1975.” The poem’s protagonist is armed with a rifle and headed to Wisconsin’s Menominee area for impending battle against an unnamed enemy.

Two-Rivers, like many Chicago Indians in the 1990s, found the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign football team’s icon, Chief Illiniwek, an exploitive insult to real American Indians. Two-Rivers joined other Chicago Indians and allies in publicly protesting the university’s profitable stereotyping and mockery of a “dignified Indian chief.” In his 2003 collection Fat Cats, Pow Wows, and Other Indian Tales, the poem “Not on The Guest List” is dedicated to Dennis Banks of AIM, who denounced the Illinois governor and others who would promote “Chief Illiniwek” and ignore the voices of non-whites.

One individual that caught Two-River’s attention in the 1980s was Carlos Cortez Koyokuikatl, who coincidentally is also a recent Chicago Literary Hall of Fame inductee. Cortez was an anti-war, pro-labor union activist who made it publicly known that he supported all indigenous acts of resistance against Northern and Southern colonialist governments. Two-Rivers was impressed with Cortez as an accomplished artist, poet, and a columnist for the monthly Industrial Worker newspaper. He appreciated Cortez’s abilities to communicate a positive message for oppressed people despite also having been a former prisoner. Not long after meeting Cortez, Two-Rivers began to write a monthly column for the Lerner Newspaper about life in culturally diverse Albany Park. He also occasionally wrote about art and poetry events that he attended across Chicago, which during the late 1980s through the late 1990s were held at public libraries, coffee houses, bars, bookstores, community centers, and even in parks.

In the fall of 1977, at Truman College on Wilson Avenue, a Chicano and American Indian month-long collaborative of Chicago Indian Artist Guild and Movimiento Artistico Chicano members was launched. This event offered films, scholarly talks, music and an art exhibition featuring photography, sculpture, and paintings. The event, called Anishinaabe Waki Aztlan, drew serious attention to our talents. Two-Rivers became friends with Chicago Indian Artist Guild founder, visual artist and emerging Comanche poet Lonnie Poco in 1985; Poco’s own poetry collection Beside the Wichita had been edited by Laguna Pueblo native William Oandason and published by MARCH/Abrazo Press. After seeing Poco’s attractive chapbook, he began writing a manuscript so he could publish his own first book.

In spring of 1991, Two-Rivers, Lonnie Poco and I read poetry for the EARTH DAY observance at the North Park Nature Center off Pulaski. This marked our first poetry readings together; Two-Rivers was in his full-voice with no microphone, giving glory in front of a beautiful tepee. Six months later, I received a phone call from Two-Rivers saying he was really interested in having a chapbook of 12 poems and he wanted to add an open letter concerning his tribe’s treaty rights. He asked it to be called A Dozen Cold Ones. I liked his proposal but of course wanted to read his manuscript. It didn’t matter to me that he had not been published in academic or established magazines or journals. I trusted he would have a good collection because I had listened to his poetry and knew he was talented.

The first 500 copies of A Dozen Cold Ones were printed at Creative Edge Printing on Southport Avenue in early 1992. His book release took place at the Green Mill. Yes, Two-Rivers electrified the audience and sold nearly 100 copies at five bucks each. His first printing sold out by year’s end and MARCH/Abrazo Press did a second run of 500 in 1993. This motivated him to reach out across the country for readings, because he knew if people could hear and see him read his poems they would buy his book.

His poetry’s success was helped by people in the American Indian community and he acknowledged people like Martin Yellow-Bank, Dee Logan, Carlos Peynetsa, Beverly Moser, Dorene Wiese, Julia Hattory, Diane Glancy, Kimberly Blaeser and allies to the cause of American Indian literature such as LaVonne Brown Ruoff, Dave Gecic, Cynthia Gallaher, C.J. Laity, Marc Smith, Michael Warr and many others who assisted him in reaching his goal of becoming a public writer of poetry and fiction, as well as a playwright and event organizer.

Two-Rivers was able to become a role model as an instructor for creative writing series that Northeastern Illinois University had created called “Writing from The Source,” allowing him to lead writing workshops for young people in various Chicago Public School classrooms.

In Chicago, Two-Rivers found his indigenous associations and close friends at the Chicago American Indian Center and had developed a collaborative series of readings. He worked with poets Mark LaRoque, Jeanne LaTraille, Lonnie Poco, Julia Hattory, and Martin Yellowbank on a number of issues.

I would be neglectful if I failed to mention Two-Rivers worked as one of the directors of the Red Path Theatre Company, the only indigenous theatre company in Illinois, which flourished with help from Chicago’s Victory Gardens Theater and the Theater Department of Truman College.

In 1995, Two-Rivers reached out to the good people at the Newberry Library’s D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian History in developing an annual successful program of music, performance and spoken words entitled, “Winter: A Time of Telling.” For 11 years, Two-Rivers played a key role as advisor or direct participant in its annual presentations, even after moving to Green Bay, Wisconsin. His last Chicago appearance was on Thursday, February 2, 2006 at a “Winter: A Time of Telling” before returning to his home in Green Bay,

Wisconsin.

Carlos Cumpián

read less