Culture comes up from the bottom. It never comes down from the top. The only thing that comes down from the top? There is a Mexican popular saying. “Las gallinas de arriba siempre cagan en las de abajo.” The chickens on the top always shit on those below.

—Carlos Cortéz

Carlos Cortéz was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to a Mexican Indian father and German mother who provided him with a multi-hyphenate, multilingual, and totally radical household. He was a singular artist of many abilities, and worked as a poet, writer, visual artist, printer, photographer, muralist, organizer, editor, and activist. We honor him today for the spellbinding life of art he created in Chicago, where he will be remembered as a beloved abuelo to generations of poets and activists.

His parents met on the street while his father was peddling copies of the Industrial Workers of the World’s chief publication, Industrial Solidarity. His mother belonged to the Socialist Party of America and wrote poetry, and his father was a Wobbly union organizer, construction worker, soapboxer, and singer—he sang in seven languages and was fluent in five.

Cortéz himself did poorly in school, “not out of lack of intelligence but lack of adhering to the academic regime.” His parents called their cantankerous young son “cabezudo” (hard head) and “dummkopf” (blockhead). And so he decided to skip college and get to work instead. Cortéz wrote his first “serious” poem in his early twenties after being locked-up overnight on suspicion. A few years later he picked up work by the Beats and thought, “Hell, I can write this shit.” When WWII broke out he became a conscientious objector to war, stating his refusal to “shoot fellow draftees” in a “gang fight for power and wealth.” He was subsequently imprisoned for 18 months and, after his release, promptly became a lifelong member of the

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

Often a trickster, Cortéz named himself C.C. Red Cloud, Koyokuikati (coyote sound), and X321826 for his many leftist columns, poems, cartoons, and etchings published in the Industrial Worker. And of all the names he owned during his lifetime, the name “friend” sticks the strongest. IWW member and oilfield worker Gary Cox wrote in the Industrial Worker newspaper: “I have never met a more gentle and honest man in my life. What you saw is what you got.” A genius at living.

Young people often asked Cortéz about making a living at art—his question back to them was, “Do you want to make a living of art, or do you want to make a life of art?” In an interview with Christine Flores-Cozza he notes: “I don’t turn my nose up at making money,” he said, “but what is more important to me is making face.”

When Cortéz bequeathed his wood and linoleum printing blocks to the National Museum of Mexican Art, he stipulated that if any of his prints became too expensive for working people to purchase, they should be used to print more and drive the price down. He used old methods to produce work, and took his time to get it right. The prints embodied physical labor and provided glimpses into the love and struggles of working people and their families. Founder and president of the museum, Carlos Tortolero, commented that, “you couldn’t separate the manual labor he did from who he was. Carlos was always about the real value of things. It was never money.”

The primary concern of his work was the liberation of working people—“mostly the idea that we can do something with our world, particularly our human society, the way it is run, so we can better appreciate all the wealth the world has to offer.” Or, as he also said: To “stop the wheels from turning.”

Cortéz believed that art is essential to human experience, and therefore everyone was entitled to it. “My greatest goal is to feel I’ve turned on others to the path of creativity. Turned on others, not only to their own personal creativity, but to work toward a truly creative society. A society that is more egalitarian, more loving of each other, more recognizing of the worth in each of us.” To him, the highest praise would be for someone to say, “That’s the guy who got me started.” “The only thing is,” he said, “you don’t teach art. You open doors. It’s one thing to show you how to push an engraving tool, handle a brush, blend colors and that. But that only liberates what is already inside of you.”

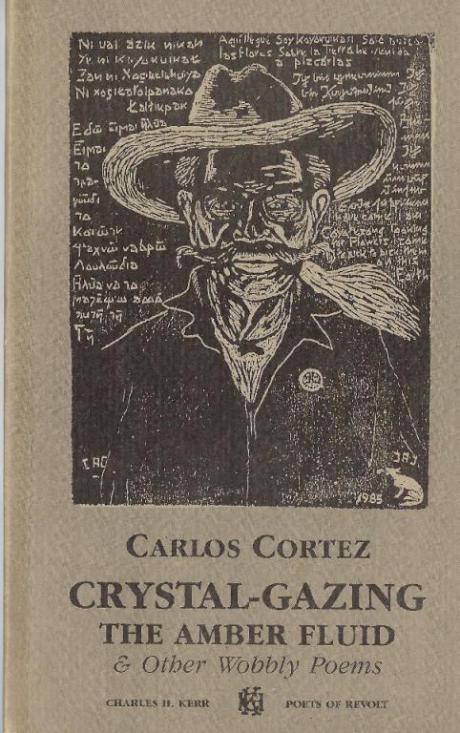

If you’re looking for credentials, Carlos Cortéz is the author of Where Are The Voices & Other Wobbly Poems and Crystal-Gazing the Amber Fluid and Other Wobbly Poems, both published by Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, as well as De Kansas a Califas & Back to Chicago (March Abrazo Press). His visual art is held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Smithsonian, the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, and elsewhere. If you want his writing—good luck. His poems, essays, and cartoons are scarcely available in bookstores and libraries. And there is a dearth of material available online, even. So it is our turn to carry his voice forward and encourage the next generations to take up his call for human ingenuity and solidarity. As our hero put it: “I think the best thing is that when you know something, you pass it on to the next person.”

May the torch we bring to this ceremony ignite something inside of you all, to carry his fire into a better future, for a better Chicago and world beyond. We need each other.

—Fred Sasaki

read less