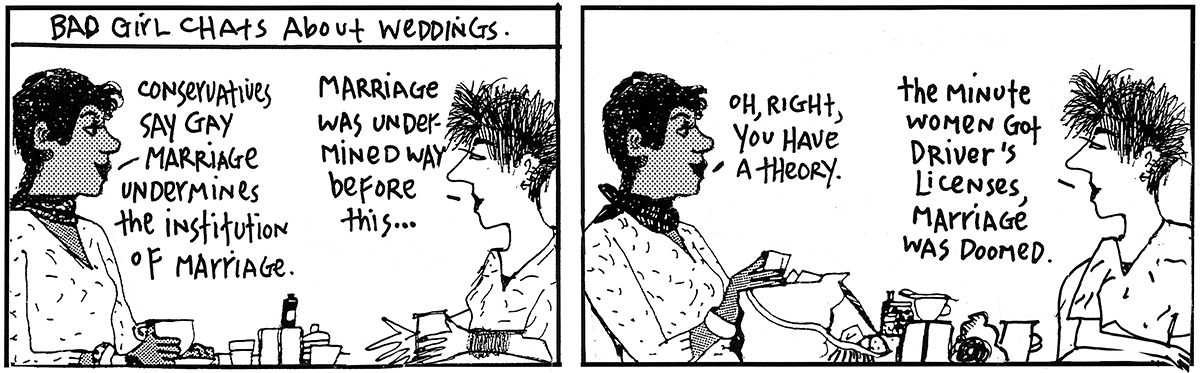

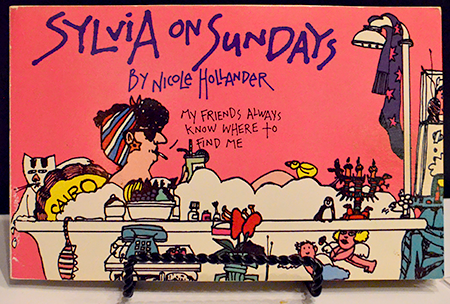

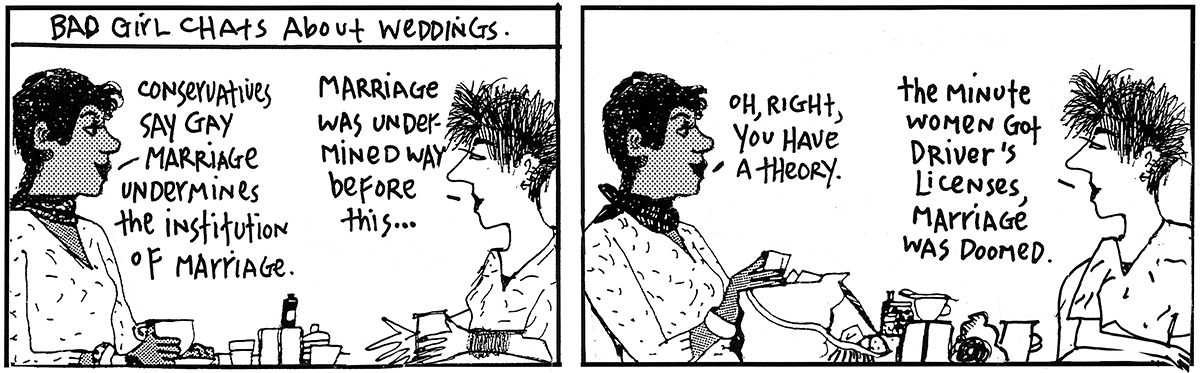

Courtner Crowder, writing Sylvia’s obituary in the Chicago Tribune on March 28, 2012, called the character a “cantankerous, 2-D feminist icon.” Indeed, Sylvia was much more liberated than forbearers like Brenda Starr, more activist than even Little Orphan Annie, and even cruder than plain- spoken Mutt & Jeff. The chain-smoking cat-lover unleashes on every imaginable subject, many of them incendiary. Sylvia was “a Chicago original,” as the New Press said in its anthology of the strip, going on to say that the comic “is nothing less than a jaded history of our times.”

The Sylvia character is a combination of three witty West Side women: Hollander’s mother and her mother’s lifelong friends, Olga and Esther. This composite gave Sylvia, in Hollander’s words, “a rough-edged, Chicago sense of humor.” Over time, Sylvia became more feminist, funny, and politically leftist. It often focused on current events and relationships, romantic or otherwise. It is not clear from the strip whether Sylvia is divorced, though she does have a daughter and an undefined relationship with a man named Harry. Hollander, in an interview with Women’s Voices for Change, called Sylvia, “like a 1940s dame.”

Hollander and her Sylvia strip had enormous influence on subsequent generations of female comic artists, including Lynda Barry and Heather McAdams. Though Sylvia might be modeled after women of the Truman-Eisenhower era, it plays well in the age of Trump. The New York Times’ Laura Mansnerus, in a 1993 feature story, depicted Sylvia as a character “who pretty much regards Republicanism as a medical disorder.” In an era where women in the hundreds of thousands march for respect, equality, and plain old justice, it is easy to see Sylvia leading the way.