WAITING FOR LUIS ALBERTO - A Personal Take

Thursday, October 28, 2021

by Marc Zimmerman

1.

When I was a young guy living near New York, I played me a waiting game. Waiting for Love, waiting for myself, and Waiting for … Godot.

When I moved to San Diego, Mexico, Minnesota and Chicago, I found myself waiting, sometimes without knowing it. Waiting for Alurista, Carlos Monsivaís, Tomás Rivera, Carlos Fuentes and Sandra Cisneros.

And yes, in San Diego, Tijuana and Chicago, I ultimately found and find myself … waiting for Luis Alberto…

Somehow we walked the same streets and trod the same roads, read and taught many of the same books, wrote books about some of the same places. But we have never met except for my sometime reading of his work and a few Facebook messages back and forth in recent years.

I could read his books and Facebook entries, but could I ever find Luis Alberto? Will I ever find him? Others may ask the same thing.

We may read of him in Mexico or somewhere on the border — in Tijuana or San Diego. But will I ever find him? Will we find him writing about Chicago? Or even Naperville?

2.

To my knowledge I have never met Luis Alberto, except to, maybe (did I do it?) shake his hand when he read from one of ;his first books about the people living in the Tijuana garbage dump at what might have been his job talk or his first public reading as a new faculty member at UIC. That was at or near the beginning of the new millennium, I believe, and by 2001 I was on my way and then gone, after 22 Chicago years, when I took a job to chair a department that housed one of the centers of U.S. Latino Literature, at the U. of Houston.

It was hello/goodbye and ne’er the twain shall or should meet. And yet I want to talk about our personal relationship, before and after that ever so brief encounter that may not have taken place (I can’t remember), even if doing so may remind us of that old Laurel and Hardy routine where the immortal boys just avoid finding each other as they, unknowingly or not, follow each other through the same train station boarding platform entrance and exit without ever seeing each other. Of course, Laurel was the writer-genius of the duo, and where does that leave me?

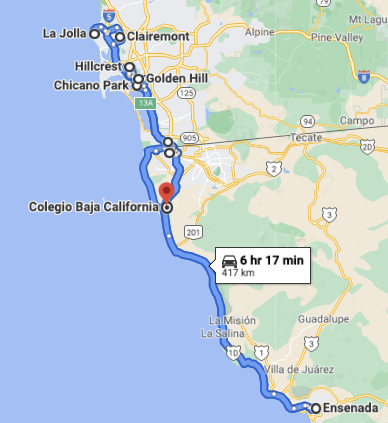

Both of us lived long in the Tijuana-San Diego border area, both of us attended the same university (though not at the same time) and of course both of us came to live in Chicagoland (though me some 20 years before him) and both have written about U.S. Latino life — though he as an Anglo-Mexicano and I as a Russian and Romanian Jewish American transplanted from my New Jersey point of birth and rearing to the San Francisco bay area for my undergrad years, and then heading south to San Diego, where I taught six years at San Diego State and studied some three as a doctoral student at the U. of California in La Jolla, crossing the border time and again (living long stretches of time in Ensenada), only to leave for Europe and then the Midwest but always returning over the years to imbibe once more at least the flavor of the border which Luis Alberto knew so much more deeply and intimately but which I too came to know. And we’ve both written at least some books about our border life, though he more inside the border than yours truly.

3.

It was uncanny reading Luis Alberto’s Tijuana-San Diego work and then reading about his life — finding him referring to neighborhoods I knew so well on both sides of the border.

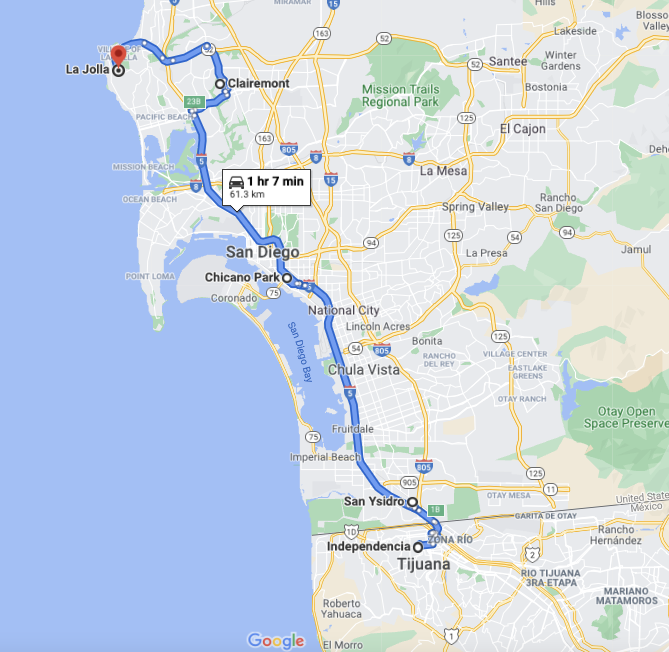

He first grew up in la Colonia Independencia in Tijuana, right near the border, not far from la zona commercial, Playas de Tijuana and the road to Rosarito and Ensenada — worlds I came to know when he was maybe 10 and had moved away. He was a sickly child in Tijuana’s mean streets, and his Anglo-American mother insisted they get him across the border, so they moved first to that intensely Mexican ramshackle border known as San Ysidro. He went to school there, and maybe he had his first McDonalds at the franchise that years later was the site of a mass killing of so many border Mexicans. On the family moved past Chula Vista and National City, past the west Logan Heights barrio, and then on further north to Hillcrest, I think, and then still further north to the Claremont area, so close to La Jolla, where he’d study theater and creative writing in the mid-1970s.

He first grew up in la Colonia Independencia in Tijuana, right near the border, not far from la zona commercial, Playas de Tijuana and the road to Rosarito and Ensenada — worlds I came to know when he was maybe 10 and had moved away. He was a sickly child in Tijuana’s mean streets, and his Anglo-American mother insisted they get him across the border, so they moved first to that intensely Mexican ramshackle border known as San Ysidro. He went to school there, and maybe he had his first McDonalds at the franchise that years later was the site of a mass killing of so many border Mexicans. On the family moved past Chula Vista and National City, past the west Logan Heights barrio, and then on further north to Hillcrest, I think, and then still further north to the Claremont area, so close to La Jolla, where he’d study theater and creative writing in the mid-1970s.

We both lived in the city at the same time for many years and knew all the spaces from San Diego downtown north to La Jolla and beyond, and south to the border: National City, Chula Vista, San Ysidro, and the colonia Independencia where he was born and lived his first years, just a short way from the border fence to the north and the road to Ensenada to the south.

In those days, San Diego was of course a tourist site, but for many of us living there, it was a sleepy Anglo-centered town dominated by active and retired military. However, later than Chicago and other points north and east, the Black power movement hit the city, and so did the Chicano movement, with Juan Felipe Herrera, a young Chicano activist and future poet laureate living pretty near to Luis Alberto in the barrio, but above all in those early days also living nearby the famous Aztlán poet, whose name sometimes gets him confused with our honoree, Alberto Baltazar Urista Heredia better known as Alurista, who I knew when I was teaching at San Diego State, a budding young student and already widely published Chicano poet, who was later working on his Ph.D. at UCSD precisely when Luis Alberto, eight years younger than the poet and some 16 younger than me, was an undergraduate theater and creative writing student in the mid-70s.

Since I’ve never talked with Luis Alberto, I’ve never asked if he knew or heard of Alurista in those early days, but I imagine he must have, just as I imagine that he had to have known of and perhaps participated in some of the growing interchanges between Tijuana and San Diego students in cross-border meetings, conferences and demonstrations. Maybe he participated or at least knew about the barrio struggle to establish Chicano Park in protest against the building of the Coronado Bridge which was set to carve up Barrio space and displace the residents, just as the UIC and expressway construction destroyed Chicago Mexicans, sending them to Pilsen and elsewhere several years before.

Surely in San Diego, Chicano empowerment was blowing in the wind and he must have known felt the breeze, and been taken by it, as he found himself becoming a Chicano or border writer no matter how blonde or white some of the local vatos might’ve seen him.

Indeed, in his many YouTube recordings, you can hear Luis Alberto speak to the pain of being a white-looking mexicano or Chicano half-breed in the San Diego streets and school. His search for identity, the level of his suffering, were great, and no matter how much he makes fun of his sense of difference and rejection, no matter how much his sense of closeness and difference has been a key to his writing, the pain is still there, although of course cushioned by his sense of fulfillment and success as a writer in which his pain has been very much part of what for him was and is “cultural capital.”

Certainly we were close enough in time and place to have experienced the spirit of the time. Maybe we attended a rally or meeting without knowing it, saw Cesar Chávez or Teatro Campesino, boycotted lettuce and grapes, picketed (as I certainly did) the barrio supermarket. But it’s true I wasn’t born in Tijuana and I didn’t live and write about the people working and living on and off the garbage dumps near the border. It would take an angel named Luis Alberto to do that.

4.

Of course, I was several years older than him when I arrived at the border age 26, to teach lit classes and creative writing at San Diego State U. I was married to an Italian-American woman people saw as Chicana. Seen as “a mixed couple,” we were often treated badly and decided to learn the culture and language as we identified with Chicanos more and more. True, we divorced less than two years after we arrived, and at that point, I became ever more fascinated with the border and Latin world I was already learning to know. I took trip after trip across that border, several trips down to Ensenada, but also east to Tecate, the Rumorosa and then on to Mexicali, San Luis Río Colorado, to Sonoita and points south all the way to Oaxaca. And at the same time, I was exploring the Chicano world north of the border. As a lecturer, I did my best to help develop African American and Chicano studies, and I coordinated faculty counseling for minority students. In 1967, I got involved in a Logan Heights African American theater group; and then with some Spanish, I got myself placed in charge of our theater group’s first outreach workshop for barrio young Chicanos.

to an Italian-American woman people saw as Chicana. Seen as “a mixed couple,” we were often treated badly and decided to learn the culture and language as we identified with Chicanos more and more. True, we divorced less than two years after we arrived, and at that point, I became ever more fascinated with the border and Latin world I was already learning to know. I took trip after trip across that border, several trips down to Ensenada, but also east to Tecate, the Rumorosa and then on to Mexicali, San Luis Río Colorado, to Sonoita and points south all the way to Oaxaca. And at the same time, I was exploring the Chicano world north of the border. As a lecturer, I did my best to help develop African American and Chicano studies, and I coordinated faculty counseling for minority students. In 1967, I got involved in a Logan Heights African American theater group; and then with some Spanish, I got myself placed in charge of our theater group’s first outreach workshop for barrio young Chicanos.

After the Bobby Kennedy assassination, I traveled more and more to Mexico and got more and more involved in the barrio. I often went to meetings at Neighborhood house and joined those picketing the local super market urging people to boycott lettuce and grapes and to resist the draft. I met Alurista there, I met Cesar Chavez, I saw the Teatro Campesino for my first time. Of course that was in the late 60s and early 70s, when Luis Alberto was still a kid, but he may have been a barrio boy living there. I certainly was not a barrio boy, but a barrio and border fellow traveler. At 12, Luis Alberto could’ve been a member of my theater workshop. He probably wasn’t, but by the 70s he was stage-struck, wanting a future in theater. I guess we were both waiting and caught up in theater… whether we met or not.

It’s also true that I was also waiting for or maybe madly seeking love in those years, and, crazy and crazed as I was, I tried to date mainly mexicanas and chicanas, failing with almost all of them, but ending up by finally marrying a Nicaraguan woman who’d lived and taught high school several years in Ensenada and who, like Luis Alberto only some eight years later, was taking undergrad classes but who had the bad luck to run into me as a graduate T.A. And while it’s true that I was (and am) 16 years older than him, it is also true that he only had five years on the boy who became my adopted son Carlos. In a way I was to meet Luis Alberto a bit by meeting Carlos.

My marriage to the Nicaraguan Ensenada mother led to much time in Tijuana and Ensenada, but also Mexico City and Nicaragua. Fellowships to do research in Spain, followed by our job offers drove us from the border area to the Midwest and the start of lives that completed my drift from creative writing even as I wrote on literature and began to make a small academic name for myself. But I never gave up my San Diego latinization, worked with Tomás Rivera-style tejano farmworkers and long-settled out mexicanos living in the West Saint Paul barrio right near the Mississippi and did the things that finally led me to a job at UIC in Chicago.

Still, if anything has enabled me to experience some of Luis Alberto’s pain deeply if vicariously, it was the experience of my son Carlos, who, born in Mexico City and spending his first years not in Tijuana but Ensenada, came with his mom to live in San Diego’s Hillcrest area as she went about getting her B.A. and Ph.D. at UCSD.

The stepson of an Ensenada doctor and thus a favored child, Carlos experienced the shock of suddenly being a San Diego chicanito, his brother kidnapped by the doctor and ending up in Nicaragua, with him taking classes in a language he didn’t understand, sitting in the back of the class, and considered backward by his San Diego school students. The situation may have gotten worse when we left Hillcrest in 1969 and moved to the La Jolla married student apartments so close to Claremont, where I believe Luis Alberto, now 14, lived his San Diego life, while Carlos, Mexican by birth, but also Central American, suffered because of his differences from the whites and also the Mexican children of La Jolla house servants that he knew in the town’s junior high.

After we moved to Minnesota, I always dreamed of going back to California, but Carlos told me he was happy to have left, never wanted to return to the discrimination and racism he felt there, and wanted to finish his high school and maybe live the rest of his life in that supposed city of racial harmony, as Minneapolis was seen in those days. (How perceptions have changed!) I stayed there to see him through school, hating much of it, not finding work as a professor even with my Ph.D., but yes building on my San Diego experiences by working with Mexican and tejano migrant farmworkers. So, in the mid-70s, just as Luis Alberto was starting his time at UCSD, I did my daily Chicano-related work in Minnesota, and yes, over time, came to see many of the Chicano performers who were to mark both our worlds — Alurista among them, but also Santana, los Lobos, also Rolando Hinojosa Smith, the novelist. Even Carlos Cumpián, a very young Chicago Chicano poet came to a Flor y canto poetry celebration in Saint Paul and got scared by the gangs, just before my then-wife, Carlos and I left for Nicaragua and the Revolution. A story not to be told here.

5.

I wonder now what professors Luis Alberto had in La Jolla. Had he studied with Rosaura or Marta Sánchez, with Carlos Blanco or others so important to my UCSD graduate years? Rosaura had a writers’ group, mainly Latinas, but maybe Luis had some contact there? I’ve never asked. I guess I’m still waiting to know.

I do know this — that after our Nicaragua time, my son graduated from high school and attending the U. of Minnesota, I left my family to take a job in Chicago, where I joined Cumpián, Carlos Cortez, Beatriz Badikian, Reggie Young, Sandra Cisneros and others to form friendships and participate in Mexican and Latino cultural projects and events throughout the city. Over the years, Ana Castillo left, Sandra left, Luis Rodríguez came and left, Achy Obejas eventually left, but Cortez, Cumpián and others, including Beatriz and yes, David Hernández stayed on.

For many years, I was virtually the only regular faculty member on the UIC campus teaching Chicano and Latino literature — this as a member of the Latin American and Latino studies program (now called LALS). And over those years, UIC’s English department, finally seeing the light, joined with LALS in an effort to hire a Chicano or Latino writer. As the lit guy in LALS, I was the one who had to court Sandra, and failed. I then tried to lure Ana and failed. Success came in spite of me when English rallied behind Ray González, who, spoiled goods boycotted by las girlfriends for an article in The Nation attacking Ana’s So Far From God, came to UIC but was unhappy and eventually took a job at the U. of Minnesota. Only then did English set aside the pesos to go it alone and court Luis Alberto. One day Cumpián called me raving about Luis Alberto’s arrival, not too long after Luis Rodríguez completed Always Running and soon after ran back to L.A. “This will bring new life to the local Latino Lit scene," Cumpian told me.

Of course it was to be and not to be. He was certainly going to grow his writerly gift, his sense of story and style, and make a big national splash felt throughout Chicago’s writerly world, but he really chose a different path, soon moving away from the city into Naperville, deciding maybe to keep the distance that would enable him to develop his writing career and co-raise his three kids — which meant limited exposure to Chicago and its overwhelming local Mexican and Latino concerns. From Naperville, Luis Alberto has used his years well to launch book after book, with the border world and Mexican connections as central to his work. Only his wonderful Into the Beautiful North gets his characters to Kankakee — maybe there’ll be a Chicago or at least a Naperville novel in the future. Who knows?

All I do know is that we never came close to meeting face to face, our lives criss-crossing but never leading to an encounter.

6.

Finishing my border trilogy gave me a pretext for getting in touch with the man who’d also done a well-known border trilogy of his own. First I wrote him a letter along with copies of my books; after not hearing from him, I wrote him through the messaging function of his Facebook page. “Hola,” I told him, “just a word to congratulate you on your many books, and especially Into the Beautiful North, which I enjoyed even as my teeth rattled. Just so you know, I lived many years in the San Diego-TJ area and when I finished the third vol. of my border trilogy I sent all three volumes to you at your UIC address.”

Back he wrote right away. “Estimado Marcos” he wrote me, as if he’d known me for years, “I’ve checked with the office but I haven’t received the trilogy.” “Hmm,” I answered. “Can you give me a different address?” “Sure,” he wrote, sending his Naperville p.o. box number. “But let me warn you, I receive lots of books, and I’m not sure when I’ll have time to read yours.” “I understand,” I wrote. “It was probably stupid of me to send your three tomes. Well, I don’t expect you to read all the stuff,” I answered, “just that you should have them and there may be a few stories you might want to read. Maybe ‘Maria de la frontera,’ or ‘The Poet and the Professor,’ about my relationship with a poet you probably know.” “Thanks,” he wrote some days later, “I’ve got them on my bedstand.” A long break occurred in communication and, following him on Facebook, I saw he was traveling all over even as he was teaching and working on The House of Broken Angels.

“I know you’re working hard on a new San Diego book,” I wrote. “So I guess I don’t expect you to read mine. But,” and here I committed a classic error, suggesting the subject of a new novel he could and should write, “do you know about Ted Williams?” I asked. “Half Mexican/half anglo like you, a fantastic hitter just as you’re a fine writer — but unlike you, he never told anyone he was half-Mexican, I guess out of fear of racism and labelling. The greatest Mexican player ever,” I added. “And a real San Diego Mexican story only you could write.”

“Thanks for the idea,” he wrote back with a certain dryness (my god, didn’t he want a baseball novel?). But I sensed I’d done something stupid. And I sensed my stories would forever sit on his table. But why should he read any part of them? I thought. And just to let him know, I wrote, “Well I’ve just finished a new book that goes beyond my border days.” “Would you like a blurb?” he asked. “Yes, of course,” I wrote, giving in. “Send me the pdf,” he answered. I did, and some days later he sent me a note saying he’d enjoyed the text, and he didn’t want to go into detail, but here was the blurb: “Every time Marc Zimmerman publishes a new book, I celebrate. He’s a wonderful writer, and this time out, he doesn’t disappoint.” I thanked him, and indeed used his blurb. But I sensed that, after I’d waited so long, this virtual contact and blurb was going to be the closest I’d come to meeting him.

7.

Yes, there still were a few twists and turns in our roads — all having to do with his wonderful House of Broken Angels.

Yes, there still were a few twists and turns in our roads — all having to do with his wonderful House of Broken Angels. First in this book, Big Angel’s family is from La Paz. But that is pure invento. Still, one day not so long ago, on a San Juan de los Cabos to La Paz roundtrip ride, my wife and I stopped in at the Tecolote Bookstore in Todos Santos (it’s just down the street from the Hotel California).

First in this book, Big Angel’s family is from La Paz. But that is pure invento. Still, one day not so long ago, on a San Juan de los Cabos to La Paz roundtrip ride, my wife and I stopped in at the Tecolote Bookstore in Todos Santos (it’s just down the street from the Hotel California).

As we talked with the owner Kate, she revealed that Luis Alberto (probably on a swing related to his then book in progress) had recently done a reading in this very place. Realizing that I’d also some pretensions of being a writer, she quickly googled my name and found that I’d done a border trilogy and suggested I should plan to do a reading the next time Lower Baja was on my itinerary. “Of course, you’re not as well-known as Luis Alberto,” she somehow felt compelled to mention (not by a long shot, she probably thought) “but I’m sure we can find a few of our regulars willing to attend.” So here without even waiting for him, I’d almost found him, only to miss him again. Damn, I thought, maybe next time he’d just happen to be here. But really, when was I planning to go back in the few years that remained me on this particular planet? At least, I took the trouble to buy The Hummingbird’s Daughter in Spanish for my Spanish-dominant Puerto Rican wife. Another meeting with Luis Alberto — at least of a sort.

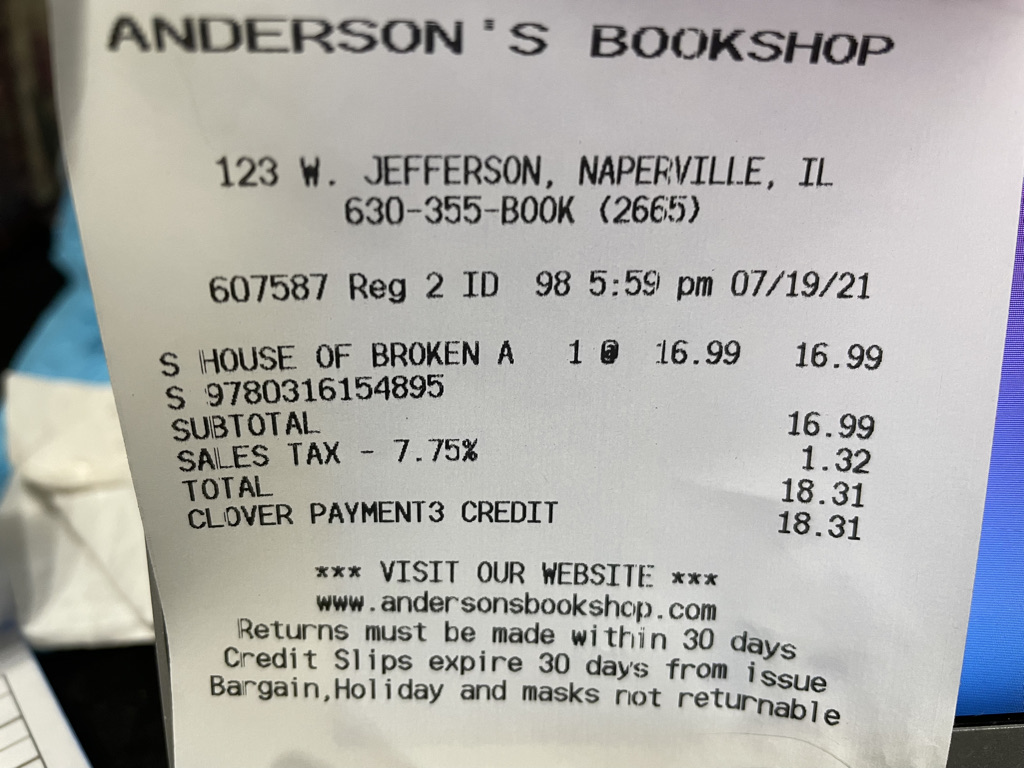

Second, his Angels book out, our granddaughter bought us tickets for the Frida Kahlo show at DuPage College, and, realizing how close we were to a certain town of interest to me, I suggested we should take the ride to Naperville; and there, as resident of Chicago for so many years, I took my first walk on the downtown streets where Luis Alberto inevitably walked from time to time. In the course of that tour on West Jefferson, I spied the Anderson bookstore, which was just getting ready to close.

I went in, looked around and then asked the saleswoman if she had any books by my favorite writers, Luis Alberto Urrea and Marc Zimmerman (always good to establish a demand). She said she couldn’t remember off hand, but went to her computer and said just what I expected to hear in my case and what I guess I wasn’t completely surprised to hear in the Luis Alberto case: “Zimmerman nothing, and who was that other writer?” “Urrea,” I told her, and spelled it out. “Ah! Here it is. We’ve one copy of The House of Broken Angels.”

I went in, looked around and then asked the saleswoman if she had any books by my favorite writers, Luis Alberto Urrea and Marc Zimmerman (always good to establish a demand). She said she couldn’t remember off hand, but went to her computer and said just what I expected to hear in my case and what I guess I wasn’t completely surprised to hear in the Luis Alberto case: “Zimmerman nothing, and who was that other writer?” “Urrea,” I told her, and spelled it out. “Ah! Here it is. We’ve one copy of The House of Broken Angels.”

I quickly went to the fiction section and found that one copy sitting on the shelf like a tortilla abandoned at a drunken fiesta. An adopter of orphans, I picked up that sad tortilla and brought it back to the saleswoman. “Here,” I said, “I’ll take it.” “Oh, very good,” she said, taking my credit card. “Don’t you know who he is?” “No,” she admitted. “But he’s a famous writer and he lives here in Naperville.” “Really!” she said. “Maybe you should get in touch with him and have him do a reading. Might be good for business.” “Not a bad idea,” she said, “although maybe he‘s done one already, and I just wasn’t around.” “Could be,” I said. “Or maybe,” she suggested, “he’s one of those writers who just wants to be anonymous so he can write his books while he lives a normal life.” “Yeah,” I said. “And maybe I’ve just blown his cover,” I said, grabbing my purchase and making for the door. “Goodbye, Mr. Zimmerman,” said that impertinent clerk, clearly blowing my little cover, with me leaving while wondering if I’d helped or hurt just a bit the elusive Naperville writer who maybe best lived remembering and reimagining his borderlands world with as little interference as possible from the likes of interlopers like me.

that sad tortilla and brought it back to the saleswoman. “Here,” I said, “I’ll take it.” “Oh, very good,” she said, taking my credit card. “Don’t you know who he is?” “No,” she admitted. “But he’s a famous writer and he lives here in Naperville.” “Really!” she said. “Maybe you should get in touch with him and have him do a reading. Might be good for business.” “Not a bad idea,” she said, “although maybe he‘s done one already, and I just wasn’t around.” “Could be,” I said. “Or maybe,” she suggested, “he’s one of those writers who just wants to be anonymous so he can write his books while he lives a normal life.” “Yeah,” I said. “And maybe I’ve just blown his cover,” I said, grabbing my purchase and making for the door. “Goodbye, Mr. Zimmerman,” said that impertinent clerk, clearly blowing my little cover, with me leaving while wondering if I’d helped or hurt just a bit the elusive Naperville writer who maybe best lived remembering and reimagining his borderlands world with as little interference as possible from the likes of interlopers like me.

8.

Now with book in hand, I sat down to read and savor a story taking place in the heart of my San Diego memory bank. So many things struck me, so many descriptions, characters, events — so many trips down to the border, so many mad landings at the airport on a plane ready to hit the buildings on our way down. Of course the central narrative of Big Angel’s party and his times with Little Angel grabbed me most as they should — Luis Alberto’s Mexican Finnegan’s Wake, his Mexican Godfather I. Beautiful in the beginning, even more so at the end, with its backyard confrontation and the final meetings with La Gloriosa and the half-brother angels.

But in the midst of it all, I found myself drawn to one passage which points to his own sense of relationship and marginality to the Mexican world, but also his grasp of the deep tragedies he reveals behind the apparent superficiality in the people he portrays — all in the space of four pages, which also point to connections deep within me and my complicated relationship to things Mexican and Latino in my own life:

They thought he had it made, growing up with English and Spanish together. And was probably rich. Everything had come so easily to him. Anything he wanted. Including their father. … They imagined his Christmas morning as orgies of bright toys and radios and bicycles. … They had seen his class lectures on YouTube.Talking about Chicano authors they’d never heard of. … He believed he was celebrating them when he shared some of their foibles. He felt the burden of being their living witness. Somehow the silliest details of their days were, to him, sacred. And he believed that if only the dominant culture could see these small moments, they would see their own human lives reflected in the other. (169)

Immediately after this revealing passage, he presents an example of something small but sacred, seemingly superficial but ultimately profound — in his remarkable description of Gloriosa preparing her appearance for the day, her effort to remain alluring and certainly more attractive than her sisters, ending with the revelation of her deep life pain, as she remembers the horrendous murder of her beloved son, which stays with her day after day in her difficult life.

And so Luis Alberto ends with this final flourish, opening to us the full weight of what he has described:

La Gloriosa covered her face with her hands and knelt as if in prayer, letting the sobs come. (171)

Of course, Luis Alberto is both inside and outside of the world he evokes. And so am I in my border stories. He in his way, me in mine. But he more in than me, whose Romanian Jewish ashkenazi side does not count as Latino after all and give me a passport to enter anywhere as fully as he. It is his position, talent and dedication that make him a “living witness” or “participant observer” but also creator of his border world. And I believe that in my own small way, that has been my own position with things Latino, as the non-Puerto Rican member of a Puerto Rican family of broken angels (one indeed named Ángel), inevitably more outside than he, who has lived through and yes witnessed the joys and deep sorrows and yes even the tragic street murders of family members seemingly so like the murder of Gloriosa’s son.

In this way, we have somehow met, though I keep on waiting to meet him in person however briefly even if for only just one time.

Marc Jay Zimmerman is Professor Emeritus of Latin American and Latin Studies (LALS) at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and of Hispanic and World Cultures and Literatures (WCL) in the Department of Modern and Classical Languages (MCL) at the University of .Houston. He has written and edited over forty books, including several on Socio-literary and Cultural Studies theory, world, Latin American, Caribbean and U.S. Latino literatures and recently, nine books of "memoir fiction""—works rooted in memory but veering toward fiction. Several of his books deal with Central American, Caribbean and U.S and Chicago Latino literature and art, with an emphasis on world systems theory, globalization, transnational processes, post-colonialism and subaltern studies. Since 1998, he has been the director of LACASA Chicago Books (www.lacasachicago.org)