Spoon River House Festival Gets Inside Edgar Lee Masters’ Old Home

Monday, September 16, 2024

by Michael Antman

“Where are Elmer, Herman, Bert, Tom and Charley,

The weak of will, the strong of arm, the clown, the boozer, the fighter?

All, all are sleeping on the hill.

“One passed in a fever,

One was burned in a mine,

One was killed in a brawl,

One died in a jail,

One fell from a bridge toiling for children and wife —

All, all are sleeping, sleeping, sleeping on the hill.”

These are the opening lines of one of the most well-regarded American poems of the first part of the 20th Century, Edgar Lee Masters’ 1915 collection, Spoon River Anthology. In free verse — at that time still a novel form of versification — the recently departed residents of the fictional Illinois town of Spoon River tell of their lives. The predominant focus, in their separate, brief vignettes, is on their unresolved life frustrations, for few of Masters’ subjects are sleeping peacefully on that hill — and fewer still talk of any kind of afterlife, nor of its comforts or torments.

Indeed, the only comfort that the 212 deceased citizens of Spoon River and environs actually experience is the freedom to finally speak their minds, though this, too, is highly equivocal given that they are, after all, dead. The overall effect of reading or watching a performance of Spoon River Anthology, then, is a distinctly autumnal one — hearing the sometimes regretful, sometimes embittered voices of those who could not, or would not, speak so truthfully of their own lives while they were still alive and capable of making a difference for themselves and those they loved. Masters’ point, it would seem, was that small-town life not long after the turn of the century enforced a kind of emotional conformity and repression that warped their lives — as one of the departed says, he’d become “one of life’s fools” — and resulted in missed opportunities, unhappiness, and unresolvable regrets.

Indeed, the only comfort that the 212 deceased citizens of Spoon River and environs actually experience is the freedom to finally speak their minds, though this, too, is highly equivocal given that they are, after all, dead. The overall effect of reading or watching a performance of Spoon River Anthology, then, is a distinctly autumnal one — hearing the sometimes regretful, sometimes embittered voices of those who could not, or would not, speak so truthfully of their own lives while they were still alive and capable of making a difference for themselves and those they loved. Masters’ point, it would seem, was that small-town life not long after the turn of the century enforced a kind of emotional conformity and repression that warped their lives — as one of the departed says, he’d become “one of life’s fools” — and resulted in missed opportunities, unhappiness, and unresolvable regrets.

There is a sort of continuing existence for Masters’ poetic subjects, however. That afterlife began soon after the initial publication of the poems in a literary journal, in 1914, for many of Masters’ poetic subjects were based on real people he’d known in the small Illinois town in which he was raised. Not all of the townspeople, however, were pleased to see the parallels with the neighbors and family members they’d known, nor with their own straitened lives.

Spoon River Anthology and its murmuring denizens have experienced another kind of immortality as well, for it is still in print and the subject, over the years, of a great many musicals, plays, documentaries and songs.

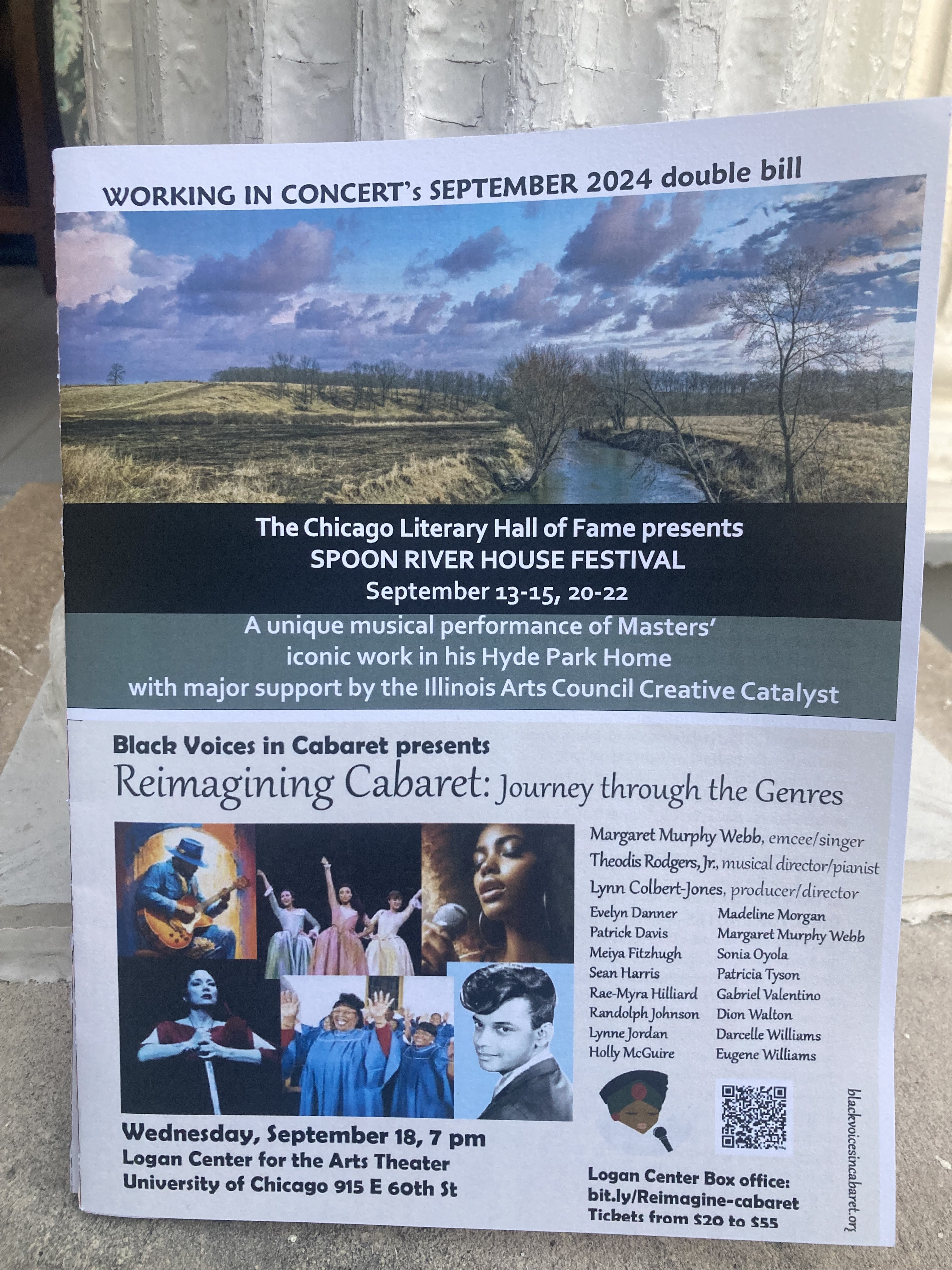

Now, Working in Concert, along with the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, is producing the Spoon River House Festival, a series of dramatic and musical performances based on Spoon River Anthology presented in the beautifully preserved home where Masters lived and wrote from 1909 to 1923.

Masters lived and wrote from 1909 to 1923.

The festival consists of three separate performances — a staged reading of selected characters from the poem on September 13 and 20, directed by Iris Lieberman; a classical concert featuring art songs that complement Spoon River, directed by Carl Ratner with musical direction by Dana Brown, and featuring compositions by luminaries of the American poetic and classical tradition including Aaron Copland, Charles Ives, Dana Gioia and Ricky Ian Gordon, on September 14 and 21; and a cabaret performance, directed by Jonathan Lewis with musical direction by Howie Pfeifer, of songs suggestive of Spoon River and its themes by Alan Jay Lerner, Kurt Weill, Harold Arlen and Roger Miller, on September 15 and 22. The entire festival was made possible with major support by an Illinois Arts Council’s Creative Catalyst grant.

Seeing the staged reading in the home Masters once inhabited — owned since 1986 by the festival’s hosts, Jim Block and Ruth Fuerst — is a holistic experience. In addition to the reading itself, attendees can gaze out the very same windows Masters looked out of as he composed his masterpiece and — for those lucky enough to arrive early — enjoy a walk around the neighborhood, where the beautiful homes (unsullied by a single modern construction or hideous McMansion) will make you think you’re back in 1914 yourself. There’s music, too, performed by John S. Green and sung by all of the characters.

The musical performances are a modest but refreshing counterpoint to the complex symphony of voices that Masters composed. John S. Green’s and Sharon Carlson’s “Drunk As I Can Be” is as entertaining as its title, and Green’s “Fiddler’s Song” is a delight. Green’s “Freedom” is powerfully performed by Adjora Stevens, who also animates some of the evening’s most memorable characters. Joanie Winter and Gerald H. Bailey offer a luminous rendering of the traditional Scottish folk song, “The River is Wide,” and the entire cast brings the production to a stirring finish with a reprise of Green’s “There’s a River.”

Just as illuminating was the post-performance Q&A, where Block made the seemingly obvious but very cogent point that Masters’ characters weren’t merely speaking from the dead — they were speaking precisely because they were dead, with a freedom they’d never enjoyed when they were alive.

The performance itself could have benefited from more of this kind of context-setting. I had the sense throughout that audience members not previously familiar with Spoon River Anthology might not have fully appreciated the fact that Masters had a larger theme at work; the individual performances were a little too individual, mere monologues, and didn’t connect as well as they could have with the other characters (the awkward blocking necessitated by the house’s small living-room performing area didn’t help) or with that larger theme. It was distracting, as well, that the performers seemed under-rehearsed and, as a result, rarely seemed to fully inhabit the characters they were portraying.

Masters himself may have attended to his own theme a bit too well. Instead of living a life of quiet desperation like his poetic subjects, Masters broke free, abandoning his family and Hyde Park home in 1923, though his wife and three children continued to live there for another 25 years. He had extramarital affairs, quarreled with his business partners (he was a lawyer as well as a poet), suffered a notable critical and commercial failure with his sequel to Spoon River, and died in poverty — the point being, I suppose, that whatever we do or say, we all end up sleeping on the hill.

Or, as one of Masters’ characters, Jonathan Houghton, puts it:

“And a boy lies in the grass

Near the feet of the old man,

And looks up at the sailing clouds,

And longs, and longs, and longs

For what, he knows not:

For manhood, for life, for the unknown world!

Then thirty years passed,

And the boy returned worn out by life

And found the orchard vanished,

And the forest gone,

And the house made over,

And the roadway filled with dust from automobiles—

And himself desiring The Hill!”

But Masters, and those who revive his work, remind us that there are also pleasures and solace along the way, including poetry, music, and cabaret. The festival, which runs only until September 22, is a wonderful opportunity to relive the work of an icon of American poetry at the height of his powers. Tickets remain for the final weekend.

Michael Antman is the author of the novels Cherry Whip and Everything Solid Has a Shadow. He is a longtime book and theatre critic and was a two-time finalist for the National Book Critics Circle’s Nona Balakian Award for Excellence in Reviewing.