Losing Dorothy: Reminiscences and Impact of Dorothy Allison

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

by Randall Albers

“An honest woman is a provocation to the meanness of the world.”—Dorothy Allison, “Spirit Healing,” Chicago Literary Hall of Fame Fuller Award Tribute to Sandra Cisneros

Gut punch.

Word came in a text from writer and longtime friend Megan Stielstra. “Do you know Sapphire?” she asked. “Yes,” I texted back. We had brought Sapphire to our Story Week Festival of Writers in 2013, a couple of years after the film of her book, Push, came out under the title Precious. ”Why do you ask?”

Because, she said, Sapphire has just posted that Dorothy Allison died.

Gut punch.

I’ve known at least ten people who exited this world in the past year or so. Warned several times that friends and acquaintances would start dying at an alarming rate once I reached a certain age, I read each of these deaths as confirmation that I had indeed reached that certain age. I knew some better than others, but nonetheless each death brought a jolt. Hearing this news about Dorothy left me hoping, of course, that it wasn’t true, that this powerful woman might still walk the earth, might continue writing and teaching and challenging us. So, for the next few hours, I paused every now and then in my day to go online in search of firm news one way or the other. Often such confirmation hangs on one word in a Wiki entry: Is becomes was. Dorothy Allison is a writer turns to Dorothy Allison was. But nothing of the sort was coming across the wire, and my hopes grew. After all, we’d just been in touch.

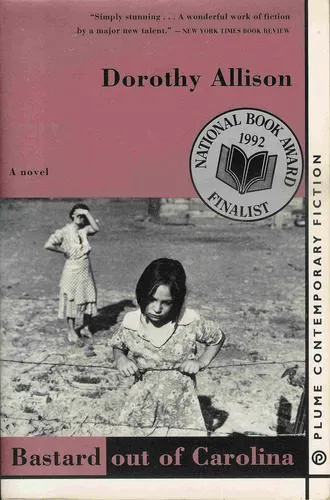

My direct experience with Dorothy went back to year 2000, though I had already felt connected to her for years, ever since I read and then began regularly teaching Bastard Out of Carolina, a book I consider one of the greatest of our generation. Though she was from South Carolina, she wrote with the hard edge of a Chicagoan, leavened with a good deal of heart. Bastard was brilliant technically, especially in the permission she deftly carved out for a first-person telling that saw and told much more than a first-person narrator was allegedly allowed to employ. And of course, she plunged into permission-carving for the material, too, about the meager wages, the sexual abuse, poverty, violence, too much alcohol, too many guns, and too little good sense.

The establishment of voice and subject matter permission had been hallmarks of writing programs at Columbia College Chicago, where I taught. Dorothy was right in our wheelhouse. Students (and not just gay students but yes, gay students especially) loved her work, and when I succeeded John Schultz as chair of what had become a Fiction Writing Department, I wanted desperately to bring her in. By 2000, we had done our first two Story Week Festival of Writers. Though we had already entertained some excellent writers at the festival, Story Week maven Sheryl Johnston and I had already seen the possibility of making a real mark in the Midwest.

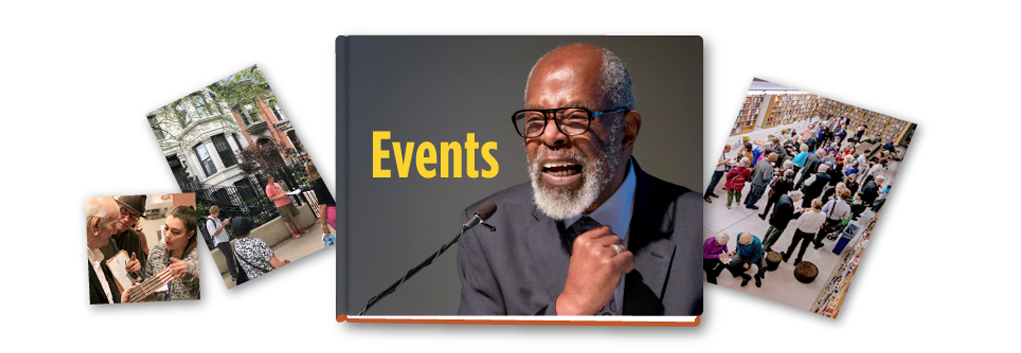

We tapped Patty McNair to explore the possibility, thinking that Dorothy would take well to a request from a young, rising woman writer. When Dorothy did indeed respond positively to Patty’s proposal, I opened my first correspondence with her, and while I didn’t know what to expect—a woman damaged and hard as nails? someone who would not trust a straight white guy, no matter what?—she could not have been nicer, and we hit if off immediately. She arrived in spring 2001 for a Story Week whose theme perfectly suited her work: “Crossing Borders, Pushing Boundaries.” Patty hosted an event featuring Dorothy and Sherman Alexie in the Winter Garden on the top floor of the Harold Washington Library. The room was packed, and CAN TV was set to tape the session, which would feature readings by both authors and a Q & A. I was proud of our Chicago audience, huge, welcoming, very diverse, and eager, buzzing excitedly.

Sherman and Dorothy were at ease immediately, noting that while their books were next to each other on the bookstore shelf, they had never met. They bantered, smiling, then laughing outright to the delight of the audience. Soon, their play turned, of all things, to blowjobs—at which point CAN TV cameras clicked off. After the event ended, the TV people told Sheryl and me that they had run into a technical problem. I wondered how many times Dorothy and Sherman had run into similar technical problems that resulted in their voices being silenced. One of the worst outcomes of that failed taping became apparent shortly after the event. Dorothy had read from a new novel-in-progress and told me that she had been struggling mightily with the scene she read that night but had misplaced the manuscript. She knew we were taping and asked if we could give her a dub because she heard in her reading that she had finally managed to get it right. My heart sank, and I had to admit what the TV people had told us. “But I’m sure we can find someone who recorded it,” I said, then began seeking out a bootleg among audience members, especially those of the substantial lesbian contingent in our program whose admiration bordered on idolatry. But to my surprise, no one had taped it on the sly, and I had to tell Dorothy that I’d come up empty. She was kind about it. “I’ll just write it again,” she said and, amazingly, waved it off.

bantered, smiling, then laughing outright to the delight of the audience. Soon, their play turned, of all things, to blowjobs—at which point CAN TV cameras clicked off. After the event ended, the TV people told Sheryl and me that they had run into a technical problem. I wondered how many times Dorothy and Sherman had run into similar technical problems that resulted in their voices being silenced. One of the worst outcomes of that failed taping became apparent shortly after the event. Dorothy had read from a new novel-in-progress and told me that she had been struggling mightily with the scene she read that night but had misplaced the manuscript. She knew we were taping and asked if we could give her a dub because she heard in her reading that she had finally managed to get it right. My heart sank, and I had to admit what the TV people had told us. “But I’m sure we can find someone who recorded it,” I said, then began seeking out a bootleg among audience members, especially those of the substantial lesbian contingent in our program whose admiration bordered on idolatry. But to my surprise, no one had taped it on the sly, and I had to tell Dorothy that I’d come up empty. She was kind about it. “I’ll just write it again,” she said and, amazingly, waved it off.

Over the years, we managed to get enough money in the department to invite visiting writers for a semester, and Dorothy was a logical choice. In addition to Story Week, she had by then done many readings around the city, including at Women and Children First. Linda Bubon, one of the founders of that illustrious bookstore, describes those early encounters: “She was an irrepressible and endearing flirt and made everyone she came in contact with feel special, me included.” Dorothy had a disarming way about her. She would look you in the eye when she talked, and while many writers love to go on about themselves and don’t ask questions, she did not seem to have that compulsion. She had clearly won our Fiction Writing faculty over, just like everyone else in the city, so when I broached the idea of bringing her in as a visiting writer the following spring, they gave their full support.

That 2006 Story Week turned out to be one of the best. For five years, we had been running a major event at Joe Shanahan’s Metro, the long-running indie music venue, where our goal was to present a lively mix of readings and music, with a dance party thrown in for good measure. Sheryl had dubbed the event “Literary Rock and Roll,” and the crowds had grown larger and more enthusiastic each year. Booklist editor Donna Seaman had joined the brain trust, bringing her extensive knowledge of the best writers and best books to the task of putting together great lineups and great shows. That year, flying under the banner of “Fighting Words: Stories of Rock and Rebellion,” the Metro show featured Tom Perotta and Alexis Pride, with music by Jon Langford of the Mekons—and Dorothy.

She came onstage that night, charged by the energy of the crowd and ready to add her own boost. She read a story from Skin, which was entitled “Her Body, Mine, and His”—but which everyone thereafter would call “Frog Fucking.” That was the first line, and Dorothy gave it with obvious relish, repeating it at full volume after it set the audience to howling, stomping, cheering. “FROOOOOOG FUUUUUCKING!” The audience howled again, rocking along, shouting the refrain. A glorious call-and-response moment. And a hell of a lot of fun, for the audience and for Dorothy, who came off the stage at the end grinning that impish grin of hers, knowing exactly what she had provoked.

Two years later, the poet Rane Arroyo asked me to co-chair the Associated Writing Programs convention set to come to Chicago in 2009. I was honored, and along with a lot of work, it bought me an opportunity to put together a major evening event. We wanted to get away from the staid and silent performance that often characterized convention readings. We would call it “Story Week Goes to AWP: Writing on the Edge.”

Naturally, I called Dorothy. The reading, I told her, would be in a large ballroom, but we were going to bring in lights, music, and readers who would amp the energy, trying as much as possible to replicate the ambience of our Metro shows. Would she do it? She was hesitant at first, until I said, “And Dorothy, I want you to read that frog fucking piece.” She laughed. “C’mon, it’ll be fun to blow the socks off those conventioneers.” She laughed that Dorothy laugh again—and agreed.

The event that night in front of 2,000-plus people was, according to AWP brass, like no event ever at any of their conventions, bordering on legendary. The lights dimmed, changed to reds and blues. A spotlight came up as Mucca Pazza, a wild group of talented musicians dressed in mismatched high school band uniforms, marched up the aisles playing at full volume. That boisterous beginning gave way to readings by ZZ Packer and Joe Meno, which were terrific and paved the way for Dorothy. She came onstage and proceeded to tell how I had called and asked her to read a particular story, then launched in.

“FROOOOG FUUUCKING!”

Standing near the back, I saw people walking by the open doors to the halls jerk to a halt, look into the room, then at each other, listening—“FROOOOG FUCKING!”—and march right in to sit down. By the middle of the reading, entranced by Dorothy’s performance, people had nearly filled the cavernous room.

Bonnie Jo Campbell was there that night and wrote recently, “I will confess that I didn't spend much time with her in the midwest. My full experience with her was in an event in Chicago that was organized by Columbia College. She read a story that I thought was called Frog Sex, but now that I look it up, I can't find it! I remember that I'd known her as a voice for those living in poverty and for women suffering sexual abuse, but when I heard her read that story (Maybe that's not the name), I was amazed at how sexy and fun and full of life she was and how she was a master of exuberant language. The audience was enthralled and rowdy and laughing and full of joy. What a wonder she was, and what a wonder her voice continues to be.”

Don Evans, Literary Hall of Fame founder and prime mover, asked me to tell something of Dorothy’s impact on the Midwest. Bonnie Jo’s statement captures something of that impact compressed into one amazing event, a power offered to an audience in the Midwest but which performed the same incantation that riveted audiences wherever she went. Her honesty, lack of pretense, liveliness, and basic humanity drew people to her.

Those qualities certainly drew me, and we forged a friendship that included talk of writing, of course, but also talk of the world, of politics, of our working-class backgrounds, of teaching, of wonderful students, of music, of revolutionary struggle, of hope for the future. And we had fun. One night, Annie and I invited her to hear music at our favorite club, Fitzgerald’s, in Berwyn. We went with Lott and Ryan, among others, a gay couple who had gone to Canada to get married when it wasn’t legal here. They had become good friends with Dorothy who, after many years with her partner, Alix, had been married in the small window where same-sex marriage had been legal in California before Prop 8 wiped it out again.

We were all having a great time listening to the blues music. I forget the band, but I was finally moved to tap Dorothy on the shoulder. “Come on, Dorothy, let’s dance!” She hesitated, “Oh, I don’t know.” Then, seeing me get up, she rose from her chair, smiling, and together we made our way to a spot on the crowded dance floor. I took her in my arms, led her into some dance that soon disintegrated. We stopped. “Sorry, Randy,” she said above the music, “but for 16 years, I’ve been leading.”

I laughed, she laughed, and I switched to a follow. “Go ahead,” I said. “I’ve never followed, but I’ll do my best. Lead on.”

We struggled through another song or two, stumbling and often stopping to laugh before starting again. Finally, the band took a break, and we made our way back to the table to cheers and clapping from Annie and our friends.

“Thank you, Randy,” she said when we were seated again.

“For not breaking any of your toes?”

“No, for bringing me here. To this club and to Chicago. This is fun, and I needed it. When I tell Alix about tonight, maybe she’ll throw caution to the wind and come out to join us.”

Though she hated flying, Alix did come out to Chicago one time, and we did indeed have some fun, hitting a club, having dim sum in Chinatown, and sightseeing. I was impressed with the bond between them, a bond characterized by ease, with serious and funny moments layered on top of each other.

I got to see Alix only once after that. Some years later, I stopped in Guerneville on a trip west, and Dorothy ushered me into their cozy living room, which was lined with jam-packed bookcases. Their son Wolf, a teenager at that time, came in and said a quick hi, answered a few questions, and then scurried out of reach of adults. Dorothy and I sat down and talked people and books and teaching and politics while all the while a fury of pops and pings and whooshes and booms rolled out the door from the next room. At last, I asked Dorothy what the heck was going on in there. She told me that Alix was fighting a computer space battle of some kind. “She may or may not come out. She’s a squadron leader and can’t leave her troops leaderless in space.” She said this not without a hint of pride amidst the headshaking irony of it all. Alix had developed a strong career as a computer consultant after getting out of the military. She had brought her electronic and strategic military training to space games.

Eventually, Alix did emerge, headphones draped around her neck. “Sorry I can’t stay and visit,” she said. I waved off any minor hint of concern on her part. “I’ve already told him why,” Dorothy put in. Alix nodded gratefully, then swung back to me. “Glad to see you,” she said—and was gone. Shortly, the pops and pings and explosions began again, which set me to laughing. The decibels of the battle finally rose to such a level that Dorothy got up and jerked her head toward the back door. “Go out to the backyard,” she said. “I’ll fix us some tea.”

I wrote to Dorothy this past summer to tell her of the death of Ryan in a car accident, and she replied that she knew “all too well” how Lott felt. Alix had died of cancer in 2022. “I am now alone with my big dog and my stubborn attitude and good neighbors,” she said. I offered a message of sympathy, and she wrote back, “Thank you, darling. It’s been a hard year. I hunker down on this hill with my big old dog and try to accept what I can’t change. Only starting to recover from losing Alix and Wolf moving down to Oakland. It’s just me and all the other widows up here. Thinking about writing again but it’s slow coming.”

Trying to accept what I can’t change. Dorothy had unpacked the relationship between lesbianism and feminism, and very early on had committed herself to revolution, to doing everything she could to change the world—working on small press magazines, doing editing for others, teaching writing seminars that paid little or nothing, building bookshelves in lesbian bookstores, taking classes from other writers with revolutionary approaches, and so on. Seeking acceptance of what she came to recognize she couldn’t change must have been incredibly difficult for her.

Above all, Dorothy loved conversations, and while she would certainly share her writerly and personal wisdom if asked, she was genuinely interested in the stories of others, especially those of the many young women who hung on her every word. I saw it in the students in our program. I saw it in my daughter, Alex, who moved to California after college and a stint in Australia. She and I drove to Guerneville from the East Bay one day and picked Dorothy up to head to a small restaurant. There, we ate lunch at metal tables in a small garden out back. Initially, Alex seemed somewhat uncharacteristically quiet, shy perhaps at meeting this woman whose work she had read as an undergraduate a few years earlier at Sarah Lawrence. I felt compelled to intervene in order to smooth the transition, but Dorothy took over, waving off my clumsy attempts and just talking right to Alex while I drifted into irrelevancy.

“What do you hope to do here, Alex?”

“Make films and videos. I am an editor.”

“And where do you live?”

“In Emeryville. But I hope to move to the Mission and find a place there soon.”

“Well, that’s great. But I have to tell you that I wouldn’t count on the Mission. That’s what I did when I first got to the Bay Area. I was broke, got a cheap place in the Mission, and just wrote. But you can’t do that anymore. Too pricey now.”

place in the Mission, and just wrote. But you can’t do that anymore. Too pricey now.”

Alex warmed, and they kept on like two old friends, Dorothy shooting me a smile now and then to let me know that it was just fine, what I was doing, listening instead of trying to be Dad. Afterward, we drove to her place across the river and got out of the car to say our good-byes. Dorothy hugged us both. “You all come back now, OK?” She stood on the low porch and waved as we pulled away.

Within a few months, Alex did move to the Mission, hooked up with Frameline, the largest gay cinema festival, and started making films and friends. When I told all of that to Dorothy over the phone, she was very pleased to have been proven wrong.

“That girl’s got gumption. Good sign.”

This past September, Dorothy and I had a chirpy exchange as I laid out plans for Annie and me to visit her on our way to stay with friends in Bodega Bay. “Sounds good,” she said. “I should be home and happy to see you.” And then, “At 75, I am more or less a fixture in a neighborhood of aging widows, dogs, and wandering deer. I will serve you iced tea or Coke and catch up a bit.”

That was September 16. I wrote back, “We can’t wait to see you.” It had in fact been too long. Annie and I set about making plans for the visit. We would fly to Sacramento, rent a car, and be in Guerneville in the early afternoon of Friday, November 1.

Then, a week later, on September 23, Dorothy wrote again. “Well, life changes abound. I am in the hospital and will be for at least another week. Surgery tomorrow. Little tumor in my abdomen. Hopeful but working on acceptance.” What must she have been thinking of? Alix, no doubt, and hopes that she had once carried for her longtime partner’s recovery. “Looks like I won’t be able to see you. Really will miss you.”

I wrote wishing her a good doctor, a good attitude, and a speedy recovery. I still imagined that we would see her—after all, it was just a little tumor—and after a week and a half passed without word from her, I ventured a note of hope that the surgery had gone well.

She wrote back, “I am resting and recovering and barely keeping up with the absurdity of life.” The surgery was over, and Wolf had insisted that she get a home health nurse to take care of her in Guerneville. “I am home,” she said, “in the house that Alix and I prepared. I still find life extraordinary and read, passionately. Still hope to finish another book and encourage my son.

“Much love, Dorothy”

In another message of the same day, she complained about being “driven crazy” by the home health nurse’s “letting me do very little. It is maddening to be treated like an invalid, but I know I am sick and exhausted and not able to answer all the questions about the WI-FI system…. Meanwhile my son is keeping track of things. I am working out my grief at losing Alix and trying to pay bills and take care of myself and the dog. Really don’t care about those pushy ladies who want to play games online.” She goes on, “I will be rid of them as soon as I can. I don’t know what things will be like by November, but I am hopeful.”

Her feistiness, her anger, always present when faced with the injustices of life but here mixed with that assertion of hope, helped reassure me that she was on the mend; and a day later, I told her, “I haven’t figured out how I can be helpful to you. If the nurses are not out of your house by November, I will come and drive them out with a stick, as witches deserve to be driven.”

Ten days later, Annie wrote to her, saying that she had been at a conference on cultural humility where “they are recommending your books, Dorothy. I am proud to know you. Your books continue to make a difference in people’s lives.” To which Dorothy replied simply, “Thank you, Anne.”

That was the last we heard from her. We did our trip to California, stopping at Jack London’s farm to see what he and his wife had constructed instead of at the house that Dorothy and Alix “had prepared.” (Prepared for what? I wondered.) I decided not to badger her further about a visit, trusting that she knew the dates of our Bodega Bay excursion. I figured that she would drop a line if she felt up to having us stop by. I was also trusting that she would be getting well and that we would see her on the next trip to California.

I carried that hope all through our time with our friends Jule and Barbara at their Bodega Bay house, all through our time up in Mt. Shasta with the grandchildren and their parents where we read books about Bigfoot and did puzzles and carried on loud Taylor Swift dance parties, all through the godawful long day of the Orange Man’s election, all through the mournful, equally long post-election day as we prepared to head back home—and finally on to the moment back home when Meg wrote to ask me about Sapphire’s post and I started my search to find out if that horrible news could possibly be true. In the end, it was Meg again who wrote later to say that present had in fact morphed to past tense in a line added to the Wiki page: “On November 6, 2024, Dorothy Allison succumbed to illness and died in her home surrounded by her friends and her dog.”

Gut punch.

I was overwhelmed with sadness. The woman who had faced so many battles with grace, focused anger, courage, and wit—and who had helped so many others learn to fight their own armed with the power of story, had fought her final battle. We had lost Dorothy.

The compression of time in these instances may leave the impression that Dorothy and I wrote and spoke often. This impression would be wrong. We communicated and saw each other more sporadically than either of us would have wished. We had developed a mutual admiration, respect, and love, but we allowed our lives’ many distractions and opportunities to interrupt our talk, if not our bond. Mostly, we enjoyed each other, whether in the halls at Columbia or in Chicago bookstore readings, before or after Story Week appearances, on brief visits in her quiet backyard with the dog and deer or down the road for the week she lent me her writing house, in a Chinatown restaurant or the garden of a small Guerneville café or at dinner in Duncan Mills in a place with a name that we would never otherwise associate with this woman, Cape Fear. I can say that whenever I was with her, I always learned something new of her intelligence, her deep feeling for people who had struggled, her commitment to her own writing and the writing of her students, her generosity, her love of life, her flirtatious and fun ways, her righteous anger, her easy laughter, her simple humanity.

I learned those things as so many others whose lives she touched learned from her over the years. My longtime colleague, Ann Hemenway, said, “She was courageous. She changed things for so many.” Another colleague in the Fiction Writing Department when Dorothy was a visiting writer, Chris Rice, asserted, “What a fearless artist. We are blessed to have met her, to have heard her singular voice, to have read her work.” Chicago writer Deb Lewis echoed Chris: “A crushing loss. She was fierce and funny. It was a true gift to spend time with her.” And Meg Stielstra, who had long ago been my student: “Oh, Randy. She was my favorite writer. Thank you for putting her in my hands when I was so young and new. Thank you for giving me her as a foundation and a guide.”

Midwest writers all.

Finally, Sheryl Johnston: “She was amazing. I’ll never forget how brilliant, funny, and kind she was at Story Week and everywhere else. She really shared what it means to be a writer. She loved mentoring students, was generous and funny with them, and celebrated their successes. She was a real mentor.”

We have lost Dorothy, yes, but not her lessons of fearlessness, fierceness, and commitment to writing, conversation, politics, sex, love, friends, and laughter. Her influence in the Midwest, as nationally and internationally, was considerable because of her extraordinarily honest storytelling and the fights she undertook against gender discrimination, poverty, racism, publication redlining, and a host of other injustices that will be remembered as her legacy. In one essay from many years ago, she says that she fully expected to die of cancer before she was sixty. We were fortunate to have 15 more years of her presence in the world than she had predicted, 15 more years in which to learn lessons offered by her living and dying. If life is a preparation for the experience of loss—“to love that well which thou must lose ere long”—Dorothy Allison taught us well that living and loving fully are at the heart of that preparation.

Randall Albers is a former Chicago Literary Hall of Fame president. He is Professor/Chair Emeritus of Fiction at Columbia College Chicago and former Founding Producer of the Story Week Festival of Writers.