Jotham Burrello to Discuss Debut Novel on Saturday, Sept. 12, 6 p.m.

Thursday, September 10, 2020

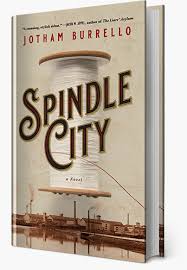

In the course of his tireless advocacy of literature and writers—a frenzied, decades-long career in which he has taught young writers, published great books, run literary festivals, and so much more—Jotham Burrello stole some hours to create his own novel. For the past ten years, as Jotham kept all his  appointments, accepted still more projects, became a flower farmer, raised three children, and enhanced his stature as an expert at the craft of writing, he…wrote. Finally, Jotham carved out time not to articulate the finer points of writing, nor edit the work of other authors, nor evaluate nascent student stories, but to lose himself in a fictional world of his own creation. Spindle City. The historical novel set in Fall River, Massachusetts, in the first decades of the twentieth century, is the project Jotham chose to implement his deep understanding of story and story craft, to turn theory into practice.

appointments, accepted still more projects, became a flower farmer, raised three children, and enhanced his stature as an expert at the craft of writing, he…wrote. Finally, Jotham carved out time not to articulate the finer points of writing, nor edit the work of other authors, nor evaluate nascent student stories, but to lose himself in a fictional world of his own creation. Spindle City. The historical novel set in Fall River, Massachusetts, in the first decades of the twentieth century, is the project Jotham chose to implement his deep understanding of story and story craft, to turn theory into practice.

“I’ve always realized, in the world of publishing about one to two percent of folks can make a living,” Jotham said. “I’ve written what I could while I pursued other things. The book is a personal story. I’ve always been fascinated by this beautiful city on the hill. My great grandfather died in a mill accident. I’ve always been motivated by class distinction in Fall River.”

Jotham was born in Fall River and now, on top of being the field manager of his family flower farm in rural Connecticut, is a tenured professor at Central Connecticut State University, Director of the Yale Writers’ Workshop, Director of the Connecticut Literary Festival, and, oh yeah, publisher of Elephant Rock Books. The Fall River area bookends Jotham’s prolific life.

The mills in the time of Spindle City dominated life in Fall River—generations of hopes and dreams were stitched to the success of the businesses and their patriarchal owners. In his travels around those parts, Jotham sees the bones of the once prosperous, bubbling town, and though it might be a graveyard of sorts he imagines those spirits rising again.

“In New England, you can’t drive to a town where the river doesn’t have a mill above it,” Jotham says. “It’s the story of the globalization of America. What did it mean to be in a mill town around then?”

In Spindle City, we join the town right at a precarious moment in the industry’s life, when prosperity is high but underlying conditions whisper doom. The novel’s kaleidoscopic opening, a June day in 1911 amidst the town’s riotous Cotton Centennial festival, sets into motion a breathless array of characters and plotlines while also establishing the fascinating historical setting. In the dense crowd, laborers, anarchists, mill managers, union organizers, society ladies, servants, peasants, prostitutes, and immigrants—representatives from the hoity Highlands down to the decrepit Cogsworth slums—jockey to see President William Howard Taft deliver his remarks. The opening mirrors, in form, that of Don DeLillo’s The Underworld, in which a baseball game and its announcer frame the complicated, intertwined pieces of the author’s elaborate puzzle.

“I knew in the opening chapter there would be a lot of moving pieces,” Jotham said. “I really mimic DeLillo’s opening. He uses a baseball announcer, I use Taft. When I found that literary model, that propelled me forward in the writing.”

At its essence, Spindle City is about yearning, but aspirations in this setting must necessarily pass through unholy gatekeepers. Justice is not a question of right and wrong, but power. The mill owners have it. The workers do not. Conscience, as much as self-interest, becomes an important element in balancing scales.

Joseph Bartlett, perhaps the town’s most influential person, takes a reluctant center stage in this story. A small mill owner whose sympathies lie at least in part with the population that makes Fall River run, Bartlett is uncomfortable with his own moral compass. Secrets of his part in a deadly fire, an illegitimate child, and the coverup of a Portuguese employee’s rape and battery at his son’s hands remain buried, but in shallow graves. Marketplace and class realities temper his instinct to support strong worker coalitions and their efforts to command just terms. He goes through life nursing a painful bad tooth, a metaphor for all that is wrong in a world that seems right.

But Bartlett serves mostly as the sun around which an ensemble of characters orbit. His children, extended family, his maid, his employees and business partners, all seek their own way in a world often unreceptive to their dreams. Sarah Strong, leader of a workers’ rebellion movement, persuades Bartlett to tour the town’s most impoverished neighborhood. Helen leads a progressive and often reckless lifestyle while aggressively courting Bartlett’s shy son Will. Maria overrules her husband’s desire for revenge in offering a kind of forgiveness to her rapist.

“The women characters are the moral center of the book,” Jotham says. “They push the men.”

In fact, Bartlett possesses a well of compassion, even empathy, but is often paralyzed at the prospect of change, or uncertainty. The female characters make sure that he confronts these tough moments. “Joseph stopped and took out his handkerchief and patted down his neck and brow. He’d hit a trifecta of crazy: Evelyn, Hannah, and now this Sarah character. But the first two were benign. This one could exile him from every decent circle in town, even the few he actually enjoyed.”

If Fall River is the bookend to Jotham’s life story, Chicago stands in the center. Jotham enrolled at Columbia College’s MFA graduate program in 1993 and for the next 18 years made Chicago his home. Jotham earned his degree and subsequently taught at Columbia, and also started his publishing company there. He lived at first around Southport and Waveland, across from the Music Box, and met his future wife Kristin at the café below. The two shared a bungalow for more than ten years in West Rogers Park off Devon Avenue, the place in which the first two of their two boys were born.

It was during his Chicago years that Jotham developed the literary discipline and instincts that decades later helped populate his own novel with richness in detail, color, intrigue, and historical precision. He learned John Schultz’s Story Workshop Method, which he describes as fundamentally derived from oral story telling. “I was fragile at that age,” says Jotham. “When I started the MFA program, they put me through boot camp. It was what I needed for sure.”

Around then, Jotham started the Story Week Reader, a journal of student short stories and nonfiction distributed in conjunction with Columbia College’s weeklong literary festival. Already, Jotham was establishing himself as a writer, editor, publisher, and all-around literary guru.

That training—all those years of intense assessment, breaking down the parts to understand the whole, his deepening appreciation for process—ultimately made Jotham into a connoisseur capable of his own literary virtuosity. This shows up over and over in Spindle City, like in the sentence, “There was so much of this business Stanton had never stopped to understand, and Joseph couldn’t help but admire the man’s total lack of concern for anyone but himself.” Each line is sculpted in a manner that would satisfy a great editor like himself. Descriptive pieces, like those of hands and clothes, work hard to place characters in context, the kind of careful, nuanced writing somebody in book acquisitions, like himself, would find attractive. The creation of particular rather than derivative storylines and moments pops off the page, at least to a trained eye, like his own.

“People look down upon people,” Jotham says. “When you read the history of Fall River, it’s all these stories of these great guys that built these great mills. There are people down shoveling coal whose voices don’t get heard. That was something we did at Columbia all the time: diversity and getting points of view.”

For sure, Jotham carried much of Chicago with him to Connecticut. Kristin drew from her time as producer and director at Redmoon Theater (she once helped plant bulbs as part of a Halloween installation), as well as classes at Chicago Botanic Garden, when launching the four-and-a-half acre Muddy Feet Flower Farm. (Lovely descriptive passages of gardens and nature also appear in Spindle City).

The literary festival Jotham now directs certainly draws from his experience with Story Week, just as the coronavirus digest he started with his students draws from the simple journal he produced back then. His workshop methods, editorial savvy, and so much more took root while he was studying and then teaching at Columbia College.

“I just love producing and making things with people, and always enjoyed mentoring people,” Jotham says. “If you don’t get into trouble and don’t spend all the money, the university is behind you. Randy Albers at Columbia taught me that. When you’re in Chicago, there is so much happening—you could go to a reading every night. When I first moved here, it was pretty sleepy. I wanted some of what I had in Chicago. My colleagues at CCSU have encouraged me to create literary programming in Connecticut.”

Jotham will be reading this Saturday, Sept. 12, from his debut novel in a virtual event sponsored by The Book Cellar. It was supposed to be a homecoming of sorts, but the health pandemic has moved Jotham’s scheduled live appearance online. He’ll converse with Patricia Ann McNair, author of And These Are the Good Times. Patty and Elephant Rock Books got their starts together when Jotham invested money he’d made selling videos into the publication of her first story collection. The event, which starts at 6 p.m., is free, but pre-registration is required.

Jotham will be reading this Saturday, Sept. 12, from his debut novel in a virtual event sponsored by The Book Cellar. It was supposed to be a homecoming of sorts, but the health pandemic has moved Jotham’s scheduled live appearance online. He’ll converse with Patricia Ann McNair, author of And These Are the Good Times. Patty and Elephant Rock Books got their starts together when Jotham invested money he’d made selling videos into the publication of her first story collection. The event, which starts at 6 p.m., is free, but pre-registration is required.

Please RSVP at words@bookcellarinc.com.

Donald G. Evans is the Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. He is the author of a novel and short story collection, and editor of an anthology. His personal blog often explores Chicago literature.