Interview with Linda Robinet

Wednesday, February 22, 2023

Sitting in the Oak Park family home that she has known her entire life, Linda Robinet projects and embodies a certain dignity, warmth, humility and generosity that radiate as she patiently listens to the conversation around her. She never interrupts. She always responds thoughtfully. Her intelligence is effortless. She grew up in this house and stayed through young adulthood, dropping out of Oak Park-River Forest High School, then, after her son Conrad was born, going back to earn her GED, as well as undergraduate and master’s degrees. Linda’s mother helped her raised Conrad as she grinded her way through university coursework and a series of jobs. Long on her own, Linda still lives just a short distance away. All the values instilled in her growing up reflect like a mirror in the two people facing her across the living room, her parents McLouis and Harriette Gillem Robinet. She even reflects the beauty and grace of her nonagenarian parents; it shows in her eyes and posture and her smil Linda served as an elementary school teacher for nearly a quarter century and now works as an executive assistant for a local recruitment marketing agency in Oak Park. She holds a certificate in elementary education, a BS in psychology (Rosary College, now Dominican University) and a master’s in Elementary Mathematics (Walden University). Summers, Linda taught swimming and managed pools, and still works in that capacity at River Forest Tennis Club. Linda, now a middle-aged, highly accomplished woman in her own right, is Harriette and Mac’s youngest child. She bears witness to her mother’s impressive and important literary career, as an intimate observer and as an educator whose scholarship encompasses her mom’s oeuvre of 11 young adult historical novels.

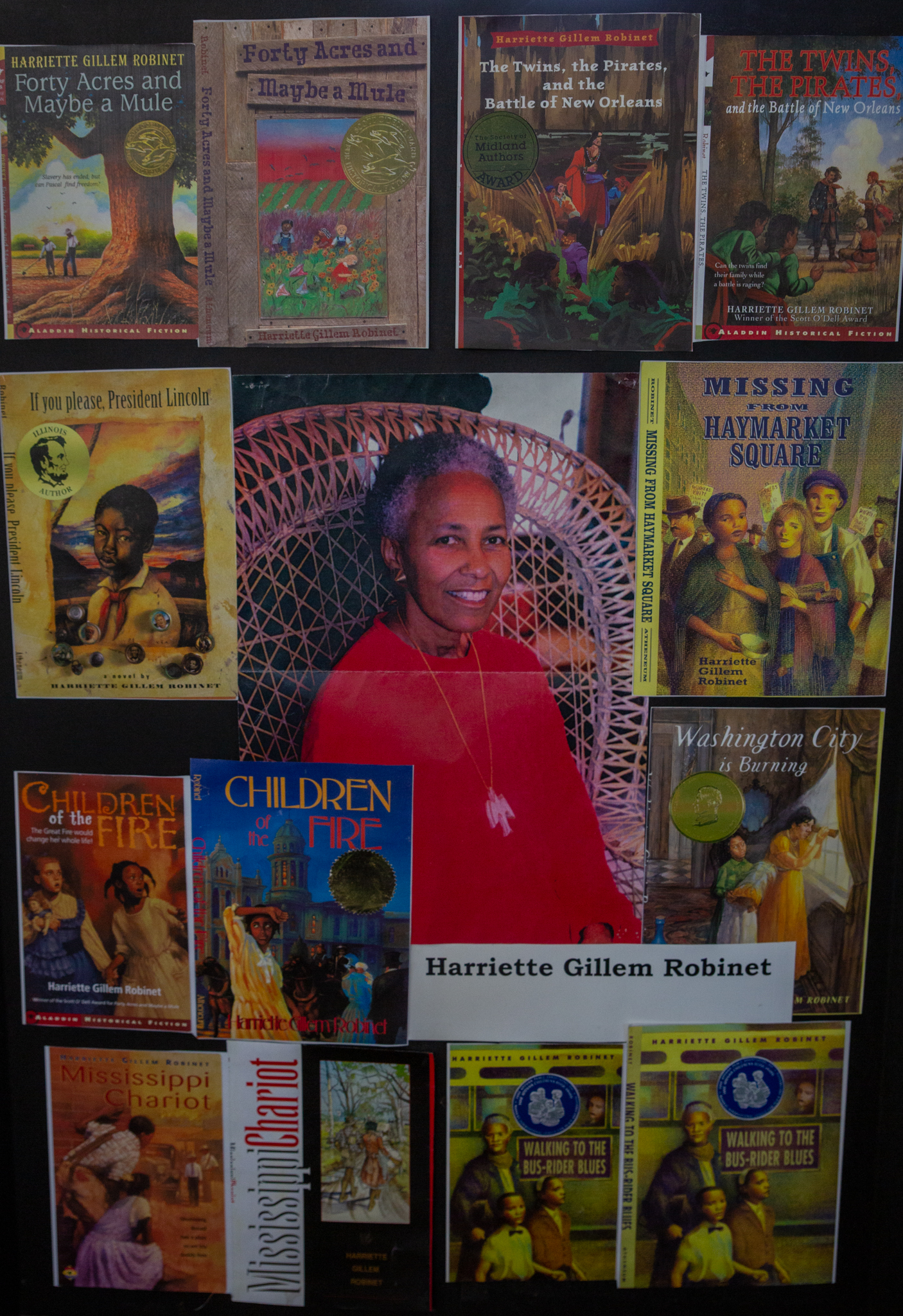

Linda served as an elementary school teacher for nearly a quarter century and now works as an executive assistant for a local recruitment marketing agency in Oak Park. She holds a certificate in elementary education, a BS in psychology (Rosary College, now Dominican University) and a master’s in Elementary Mathematics (Walden University). Summers, Linda taught swimming and managed pools, and still works in that capacity at River Forest Tennis Club. Linda, now a middle-aged, highly accomplished woman in her own right, is Harriette and Mac’s youngest child. She bears witness to her mother’s impressive and important literary career, as an intimate observer and as an educator whose scholarship encompasses her mom’s oeuvre of 11 young adult historical novels.

It is through Linda that we’re able to access memories and deeper insights into Harriette’s work. Harriette, at 91, suffers from Alzheimer’s. The first signs of memory loss began in 2016 and her symptoms accelerated to the point that she gave up writing. She’d stopped doing public appearances a decade and a half early, mostly due to her advanced age. Harriette’s condition, now severe, prevents Harriette from any real recollection of her life as a writer, even the fact that she has written the books she has written.

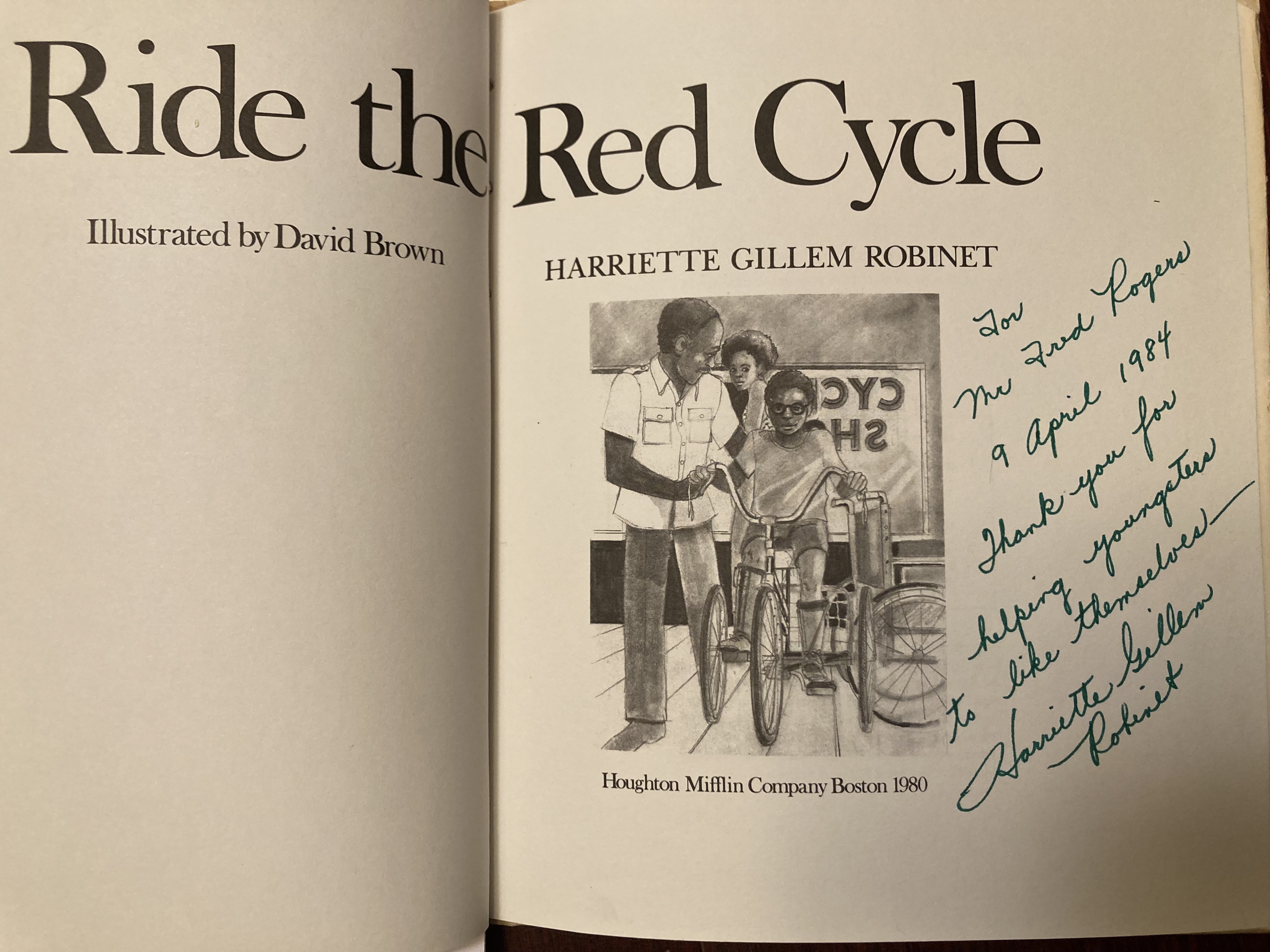

In this comfortable, casual setting, Harriette reacts to conversation with joyful smiles and playful expressions of “Oh, wow!” She is able to process and understand much of the surface conversation, even to answer—accurately, it seems—basic questions. She signs my personal copies of her novels in pretty, legible cursive. But as with all Alzheimer’s sufferers, Harriette’s memory is shallow and unreliable, a curse which does not cause any of the Robinets, including herself, to outwardly alter their treatment of each other. The love and respect and pride the family has in each other remains steadfast.

Linda, though, is able to fill in some of the inevitable blanks.

DGE: You're the youngest of six children. When you were six years old, your mom published her first novel, Jay and the Marigold, about a young boy with cerebral palsy watching a flower grow. For this novel, did your mom draw from her experience raising your brother, Jonathan?

LR: My mother definitely drew on her experiences raising my brother Jonathan for her first two picture books. When Jonathan (and my sister Marsha- both were adopted at the same time) was adopted from Catholic Charities, my parents did not know that he had cerebral palsy, nor did they have any details about his birth parents. As Jonathan and Marsha grew and developed very differently, both of my parents did everything in their power and means to help Jonathan. They went to doctors, specialists, therapists, opthalmologists, speech therapists, physical therapists, the list is too long to include everyone.

From my understanding, my mother was at the library in Oak Park one day. One of the librarians had just returned from a conference of librarians. She had a conversation with my mother regarding the needs of the literary world. The librarian told my mother that there was a great need for books for children that included characters with a variety of disabilities. My mother said, "I could do that," and she proceeded to write Jay and the Marigold.

I have also heard that my mother was inspired by a moment when Jonathan was watching an episode of Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood on Channel 11 WTTW  Chicago. Jonathan was sitting on the floor wearing his long-legged braces, already having had a few of the operations on his legs. Mr. Rogers said, "I like you just the way you are," in his gentle, conversational way, looking directly at his television audience.

Chicago. Jonathan was sitting on the floor wearing his long-legged braces, already having had a few of the operations on his legs. Mr. Rogers said, "I like you just the way you are," in his gentle, conversational way, looking directly at his television audience.

My brother responded, "But, my legs no go-go."

Mr. Rogers replied, "I do like you just the way you are." My parents eventually shared this story with Mr. Rogers who years later came to visit our family. My mother was watching this conversation between Jonathan and Mr. Rogers, very emotional. She wanted him and other children with disabilities to see themselves in stories and to like themselves just the way they were.

DGE: Reading the novel as an adult, what aspects of your family history did you recognize in the story, and what techniques did your mother employ to transform biography into literature?

LR: Any time I read any of my mother's books, I hear her voice. She always articulated with precision and a slow tempo. My mother made a concerted effort to NOT include our personal family history in her books, out of respect for our family's privacy. With the exception of Ride the Red Cycle, none of the characters or situations had connection to instances or traits of us children. Ride the Red Cycle was written soon after my father had created a hand-crank, quad-cycle for Jonathan. There is a lovely article in the Wednesday Journal about my father's invention back then and mentioned in this article.

The family history aspects that I recognize in all of my mother's books is the concept of always learning and striving to understand. I know this quote is overused but it is poignant as a message of my mother's writing and our family history: Of her books, Harriette says (on her website), “Unless we know our history, we have no perspective on life today. How can we know where we’re going, or appreciate where we are today, if we don’t know where we’re coming from?”

My mother, my parents, wanted us to strive for learning and understanding of our own history and the history of many cultures. My mother's father was a junior high school teacher of history and geography. My grandfather instilled in my mother a desire to learn about everywhere in the world and the history of those places. A magazine that I fondly remember always being the centerpiece at our house and the starting point of many dinner conversations was National Geographic, which was also something she read with her parents.

I think a technique my mother used to transform biography into literature was to tap into empathy. I remember often talking "on the stairs" (my siblings and I were sent to sit on the stairs to think if we had made a mistake) about "How do you think they might feel?". If I were to have to speculate about how she wove her own biography into her stories, it was to come from a place of understanding.

My mother did not write fantasy, she wrote multicultural historical fiction. She loved to research, always learning more and more, as her father had taught her. It was a challenge for her to integrate historical facts with fiction to bring history to life. My mother is a natural writer but her writing is not fanciful. She writes with rigor and with a purpose...to bring history to life.

DGE: By the time you were born, your mother was 40 years old and there were six children in the house. As you were growing up, did you observe the ways in which your mom managed to steal some writing time amidst her duties raising a large family and maintaining the household?

LR: Reading, writing and homework were always being done in our home. Someone of my siblings were always reading for a book report; going to the library to get books or study; making flashcards for test review; editing a paper or essay that had been written; etc. My mother often wrote as we were doing homework. She'd be writing at her desk in the dining room while a few of us would be working at the dining room table. She'd be writing with her laptop turquoise desk on her lap in the den, where our television is, to monitor our comings-and-goings. My mother kept a rather strict cleaning, cooking, shopping, laundry schedule that involved getting her tasks done efficiently so that she had time to write. My siblings and I were raised with chores. The duties of the house were divided up between us kids, and my mother monitored like a hawk. The rule was that we had to get our chores done before we could play. She taught us the duties of the house very well, including cooking dinner once a week when we were old enough (so even the meals were divided up, including the shopping for ingredients, preparing the meal and cleaning the dishes). She is a phenomenal mother whose full-time job was preparing her children to be independent, self-sufficient adults. My father also taught us to change oil in our cars, rotate tires, cut the lawn grass, shovel snow, wash the storm windows (taking them down and putting them back up was an entire family project) and endless science experiments in the basement. From my days at home from elementary school, when my older siblings were in junior high or high school or off at college, my mother's days at home were spent cleaning, meal preparation, then she'd write like it was her job.

LR: Reading, writing and homework were always being done in our home. Someone of my siblings were always reading for a book report; going to the library to get books or study; making flashcards for test review; editing a paper or essay that had been written; etc. My mother often wrote as we were doing homework. She'd be writing at her desk in the dining room while a few of us would be working at the dining room table. She'd be writing with her laptop turquoise desk on her lap in the den, where our television is, to monitor our comings-and-goings. My mother kept a rather strict cleaning, cooking, shopping, laundry schedule that involved getting her tasks done efficiently so that she had time to write. My siblings and I were raised with chores. The duties of the house were divided up between us kids, and my mother monitored like a hawk. The rule was that we had to get our chores done before we could play. She taught us the duties of the house very well, including cooking dinner once a week when we were old enough (so even the meals were divided up, including the shopping for ingredients, preparing the meal and cleaning the dishes). She is a phenomenal mother whose full-time job was preparing her children to be independent, self-sufficient adults. My father also taught us to change oil in our cars, rotate tires, cut the lawn grass, shovel snow, wash the storm windows (taking them down and putting them back up was an entire family project) and endless science experiments in the basement. From my days at home from elementary school, when my older siblings were in junior high or high school or off at college, my mother's days at home were spent cleaning, meal preparation, then she'd write like it was her job.

DGE: Where did your mom write?

LR: To the best of my memory, my mother wrote in four different places:

1. She wrote at the desk my father set up in the corner of the dining room. She'd have her piles of notebooks and books that she used for researching in neat piles.

2. She wrote in the den/tv room or on the front porch, if the weather was nice, using her turquoise laptop desk. If we kids were playing outside during the late spring, summer or early fall, my mother was often sitting on the front porch, keeping watch while writing.

3. My mother had a writing desk in the room my two older sisters shared, once they had completed college and moved away from home. After I moved away. She had a computer by then, though she started with the typewriter then moved onto a word processor and eventually a computer.

4. My mother had a writing desk in the room that was my room when I was a child that my father built for her. She worked back and forth between the two bedrooms. When I would come to visit with my son, I would often hear the clack-clack-clack of the keys from upstairs.

DGE: Tell me about the house on 214 S. Elmwood. It's been in your family nearly six decades. What was that house like when you were growing up? What was Oak Park like?

LR: 214 South Elmwood was more than a home, it was a sanctuary. Not many adult children can say that their parents still live in their childhood home or that they can always go "home." The house was where my parents taught me how to cook; clean; do well in school; become responsible; love and lose pets; have every "first" that typical childhoods are filled with; and it also was the home that I brought my newborn infant son to for the four weeks of my maternity leave. The 200 South block of Elmwood was extraordinary: at one time its claim to fame was having over 70 children under the age of 18. My best friends since birth grew up there, we stood up in each other's weddings, welcomed each other's babies, and grieved when their parents passed away. It was a block that was filled with summer memories of playing Jail Break, catching fireflies or walking to Ridgeland Commons pool or hill together. The house was never quiet; it was filled with music (we all took an instrument, all of us took the piano); we had a record player that played many different types of music, from folk, to metal, to alternative, to rock and roll; we often played elaborate make believe games, usually led by our eldest brother, Stephen, that involved building forts and wearing costumes. The house had routines like chores before playtime; dinner together, all around the table in the dining room, and every meal started with prayer; taking turns watching television shows especially Saturday morning cartoons; making lunches the night before school; and going to church weekly at St. Edmunds. We camped every summer at the Indiana Dunes and frequented local museums, constantly learning.

By the time I went off to elementary school, Oak Park was a different Oak Park from the one my siblings grew up in. I knew what my brothers and sisters had experienced, but I did not experience anything racially motivated (oddly enough not until I went to college as a single mother). Oak Park was a community that I would consider to be perfect to grow up in. I loved my schools, so much so that I taught at the elementary school for 24 years that I had attended and my son attended. I loved climbing trees, playing outside with friends, walking to the mall to shop at Woolworths, catch a movie at the Lake Theater, eat a hot dog from Tasty Dog, read books at the library, or get some candy from Katie's Country Candy Store. Oak Park was full of park district activities like fishing during the summer, swim lessons at Oak Park-River Forest High School, sledding on Ridgeland Commons hill during the winters, or building a sledding hill down our front porch stairs (often zooming out into the street).

DGE: Your parents bought the house and began living there in 1965, when discrimination in the housing market all but prevented a Black family from ownership. Your parents still live there today, in an Oak Park that has grown from a white, entitled, bigoted community to one that prides itself on diversity and inclusivity. Were you aware of the house as a symbol of progress, or in other ways cognizant of your place in a movement toward social justice?

LR: My mother and father are storytellers. I grew up understanding that our "home" was very symbolic of the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement. I listened when Bob and Lynn Bell would visit or Don and Joyce Beisswenger stopped by about their efforts to help my family find their forever home to raise their children in a safe community. I do not believe that I had a place in the movement toward social justice, but I reaped the benefits of the peaceful efforts of my parents and siblings.

DGE: Your mother carried on the duty of raising six children while finding success as an author. Tell me a little bit about how this changed her life, if at all.

LR: My mother LOVED being a mother, I do not doubt that or question whether she'd have led her life a different way. And, I know that she enjoyed the work she did before children (BC as we kids would joke) and had been known to say that writing helped her keep her sanity while raising children. After I became a mother, I developed a new respect for my mother. She made the enormous sacrifice to help raise my son, starting when he was four weeks old while I went to start college, then started teaching and while I got my master's degree. When we would talk about parenting, my mother shared that she lost herself in diapers (cloth diapers back then that had to be washed), nursing or bottles, nap times, bedtimes, snacks, breakfast, lunch, dinners, shopping (there was a time that she went grocery shopping every day...we'd go through a gallon of milk every day), laundry, laundry and more laundry. I would speculate that writing absolutely changed her life, it gave her an adult purpose beyond children; it challenged her mind; it woke up her creative spirit; it fulfilled her spirit for learning.

DGE: You're a teacher. Tell me a bit about your career in education.

LR: Just this year, I have taken a leave from teaching.

For 24 years I taught elementary education, 18 of those years at the 4th grade level. Twenty-one of those years at Beye Elementary, where I went to school and my son went to school. A huge reason why I went into education was because of my parents. My mother shared books with me, read to me at bedtime, helped me with my schoolwork every step of the way and I became an avid reader. My early dream was to become a ballerina, but reality set in and I debated between a teacher and a librarian. My mother and father were my first teachers. They were patient and encouraging. They were loving and joyful. They were passionate and enthusiastic. I wanted to give children what my parents and siblings had given me.

Since I started teaching in my own homeroom, I have always used my mother's books. I used Ride the Red Cycle and Jay and the Marigold to teach about empathy and diversity. I used all of her books for reading, writing, social studies and history. When I taught Chicago History, I would read Children of the Fire and my children identified with Hallelujah. When I taught Missing from Haymarket Square, my class would go to Haymarket Square for a field trip and delighted that Hallelujah had become so successful and helpful as an adult working at the soup kitchen. In social studies, when we learned about government and our presidents, we'd read If You Please, President Lincoln and were shocked to learn about different policies when all they knew was about the Emancipation Proclamation. When we'd learn about the Civil Rights Movement, we'd read Walking to the Bus Rider Blues and we'd talk about the elements of a mystery. My mother has been woven in every year of my teaching and generations of students were exposed to her writing.

DGE: At the heart of your mother's books are themes of social justice, acceptance, compassion, and empathy. Some of those themes arise organically, others are more insistently placed within the context of the story. As a teacher, what about these stories and the characters within strike you as useful for classroom instruction? Why is it important for young people to learn about differences in circumstance and race and the ways in which prejudice might be unraveled?

LR: My mother's stories are relatable. Students hear that inner voice that my mother writes so well. And, something my students have shared over and over again over the years, is that my mother's characters were never perfect, just like them. Her characters were scared and brave. Her characters were angry and loving. Her characters were disabled and differently abled. Her books are so powerful for children because they get to experience the historical events through the eyes of the characters. My students would often fumble to find the words to explain what they learned about prejudice and if I were to summarize the gist of their sharings, it is that prejudice became humanized. Prejudice was about fear and differences and blame and bottom line, it was about not understanding and being willing to learn. My students often felt so empowered because they felt like they were more likely to be open minded than adults. My mother's books gave them hope that children have power through understanding our history, understanding biases, stereotypes, preferences and that there is no shame, but there must be awareness.

LR: My mother's stories are relatable. Students hear that inner voice that my mother writes so well. And, something my students have shared over and over again over the years, is that my mother's characters were never perfect, just like them. Her characters were scared and brave. Her characters were angry and loving. Her characters were disabled and differently abled. Her books are so powerful for children because they get to experience the historical events through the eyes of the characters. My students would often fumble to find the words to explain what they learned about prejudice and if I were to summarize the gist of their sharings, it is that prejudice became humanized. Prejudice was about fear and differences and blame and bottom line, it was about not understanding and being willing to learn. My students often felt so empowered because they felt like they were more likely to be open minded than adults. My mother's books gave them hope that children have power through understanding our history, understanding biases, stereotypes, preferences and that there is no shame, but there must be awareness.

DGE: Describe your mother's personality and temperament. What inspired her to be a writer?

LR: My mother is classic. She is always professional and reserved. She is well-spoken and eloquent. I would speculate that my mother felt constant pressure to represent the African-American race well. She was a representative of what her ancestors had fought so valiantly for. Her temperament was calm, in control, and polite. She is soft spoken and gentle though incredibly strong. If any of my siblings or myself had made a mistake, my mother would lower her voice, that's when we knew we were really in trouble. She is value driven and her faith is her guide. She was always reading and learning something. She was almost militaristic in how consistent her habits were like praying, exercise, healthy eating, always learning, writing. Even now, she writes down what happens in her day and rereads, though she does not remember the events she writes about.

What inspired my mother to be a writer? I wish my mother could answer this question herself, it is one I have never asked. I have lost my mother to Alzheimer’s, she doesn't even remember that she wrote any books.

I think my mother has always been a writer. I do know that her father made her write during the summers when she was a child just like she did with me. I do know that she had lived such a full life and had stories to tell, but not her own. She was incredibly humble. I did ask her why she never wrote a book about what it was like growing up during segregation or marching during the Civil Rights Movement or the stories of our ancestors who were slaves or what it was like growing up during World War II when her brother was in the Army, so many amazing stories. She never felt that it was her place to write those stories and she was deeply respectful of never offending or misrepresenting my siblings and me.

DGE: Your mother's accomplishments are wide and varied. How much pride did she take in her accomplishments as an author? What kind of importance did she place on creating these meaningful stories and finding an audience for them?

LR: My mother (and father) were incredibly humble. She was never prideful about anything in my memories. Even when she received awards for her writing, she always spoke about her gratitude for the support of friends, family, editors, her writing group and the bigger message of learning about history. My mother did not necessarily write to find an audience, she did not write for fame, she did not write for recognition. I remember that my mother, when she wrote an article for Red Book Magazine, she said something like I am a mother, not a pioneer. I think she would also say the same about writing, she just jotted a few words down in a notebook, loved the process and was pleased that people enjoyed her stories. She was never boastful or a braggart; humility to the extreme.

Donald G. Evans is the author of a novel and story collection, as well as the editor of two anthologies of Chicago literature, most recently Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry. He is the Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.