Hamlin Garland’s Chicago

Monday, April 8, 2024

For a bright moment, a decade or so around the turn of the twentieth century, the city of Chicago was the capital city of modernity, a place to which observers from around the world looked for a glimpse of the future. This had something to do with Chicago’s position at the hub of America’s continent-spanning railway system and its status as hog butcher to the world. It had something to do with the fact that Chicago’s slaughter-house and factory owners managed to pull off an event that astonished the world, transforming a swampy patch of the South Side into a neo-classical fantasia with a World’s Columbian Exposition that signaled the city’s boundless capacity for Faustian self-creation. And it had, this essay will argue, at least a little to do with Hamlin Garland.

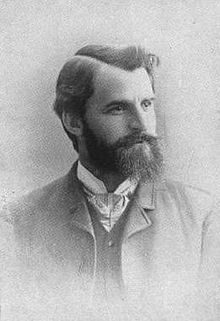

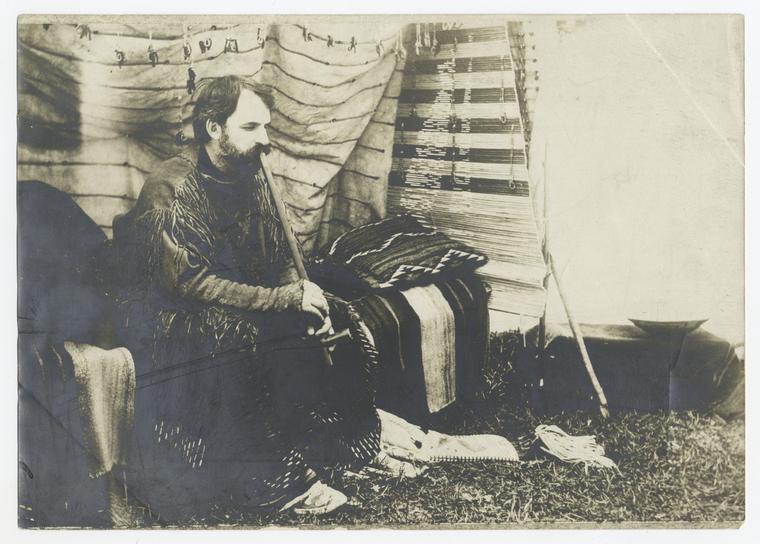

Garland, to be sure, was not a lifelong Chicago writer along the lines of James T. Farrell, Henry Blake Fuller, or Gwendolyn Brooks. He fell more in a broader category of writers whose work addressed Chicago as an engine and symbol of the national social upheaval in the industrial decades from the Civil War to the Second World War—writers like Richard Wright, Theodore Dreiser, or Upton Sinclair, who sojourned in Chicago for varying periods of time, and yet whose work is indelibly associated with Chicago’s place in the broader American story. Though he endured Chicago’s winters for roughly a quarter century (and in the logic of the boast, deserves credit as a Chicago writer on that basis alone), he was also, at various points in his life, a Boston writer, a New York writer, a Wisconsin writer, a Klondike writer, a Dakota territory writer, an Indian territory writer, and an early film writer whose screen plays on Native American subjects were filmed in California. But although he was all over the map, his imagination made the map as a writer who shaped an emerging Western literature around the imaginary geography of what he called the “Middle Border.” This came from Garland’s understanding of himself as a writer who traveled to many places, but who viewed Chicago as an integrative touchstone for his experience and that of the century. When he moved to Chicago in the early 1890s, he brought with him an agenda that still defines some of the key terms of twentieth century literary cartographies, and it was his years in Chicago that allowed him to refine and articulate these points in a way that would ultimately shape modern American literature.

Garland’s life before Chicago divides into two periods. Born in Wisconsin in 1860, the son of a farmer possessed by the idea of “westering,” Garland spent his childhood under the sign of the Homestead Act, moving from one farm to another as his father searched for the land that would make him rich. It never happened; each farm—first in Wisconsin, then Iowa, culminating in a stint on a Dakota homestead— was as unprofitable as the last. The experience raised more existential questions than it did marketable crops. In the 1880s, during his young life’s second act, Garland abandoned his father’s path and made his way to Boston, paying his way in part by work as a carpenter, attracted to political movements and theories that could help him make sense of his experience, and seeking a career that did not involve manual labor. Oratory was his first ambition; it combined his political ambitions with a very typically nineteenth century way of thinking about becoming a wordsmith. But Garland soon became interested not only in literature but in theorizing literature. Already during his Dakota period he was reading the latest in French literary theory and drawing up maps and histories of literature that would include and speak to America as he experienced it.

By the early 1890s, Garland had found a voice and the approach for which he would be most remembered, becoming a writer of what the twenty-first century calls “place-based” fiction, the twentieth century called “regionalism” and the nineteenth century called “local color.” In an era that celebrated local particularity—and which cultivated nostalgia and sentimentality as the appropriate modes for experiencing and expressing that particularity--Garland’s short story model intervened to define a distinctly more modern sense of “local color.” The landscapes of his stories were beautiful, but his farmhouses were grim; his farmers struggled against the elements and the grip of the mortgage payment. His plots turned—in a way that anticipated twentieth century regionalisms—on the love-hate relationship the children of marginal and rural communities have to the spaces they have only partly escaped. Can the successful son ever return? Does he still speak for those who stayed? And, when his stories were collected and interconnected in his first volume of stories, the 1891 Main-Travelled Roads, that concern for how the local person connects to the space and culture that formed her translated into a larger effort to evoke local worlds as spaces of historical transformation. Under the sway of Mark Twain and other Reconstruction-era writers, Garland first referred to the territory of his imagination as the Mississippi River Valley. Later he would come to call it the “Middle Border.” Not a fixed region that could be located in geography books but a culture connected to a changing economy, his ever-shifting internal and imaginative frontier was, for Garland and his readers, a projection of the experience of settlement. As he later put it, the “middle border ... does not exist and never did. It was but a vaguely defined region even in my boyhood. It was the line drawn by the plow and, broadly speaking, ran parallel to the upper Mississippi when I was a lad. It lay between the land of the hunter and the harvester.” [1]

particularity—and which cultivated nostalgia and sentimentality as the appropriate modes for experiencing and expressing that particularity--Garland’s short story model intervened to define a distinctly more modern sense of “local color.” The landscapes of his stories were beautiful, but his farmhouses were grim; his farmers struggled against the elements and the grip of the mortgage payment. His plots turned—in a way that anticipated twentieth century regionalisms—on the love-hate relationship the children of marginal and rural communities have to the spaces they have only partly escaped. Can the successful son ever return? Does he still speak for those who stayed? And, when his stories were collected and interconnected in his first volume of stories, the 1891 Main-Travelled Roads, that concern for how the local person connects to the space and culture that formed her translated into a larger effort to evoke local worlds as spaces of historical transformation. Under the sway of Mark Twain and other Reconstruction-era writers, Garland first referred to the territory of his imagination as the Mississippi River Valley. Later he would come to call it the “Middle Border.” Not a fixed region that could be located in geography books but a culture connected to a changing economy, his ever-shifting internal and imaginative frontier was, for Garland and his readers, a projection of the experience of settlement. As he later put it, the “middle border ... does not exist and never did. It was but a vaguely defined region even in my boyhood. It was the line drawn by the plow and, broadly speaking, ran parallel to the upper Mississippi when I was a lad. It lay between the land of the hunter and the harvester.” [1]

Garland’s fictions jolted his contemporaries and began to win him a national reputation. Chicago, however, would provide the stage on which these fictions, and the ideas behind them, could become nationally and even internationally prominent. In May of 1893 Garland attended the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and managed to invite himself onto the “Modern Fiction” panel at the Fair’s Congresses, where he provoked Mary Hartwell Catherwood (herself a Midwest writer) into a debate on modernity and literary tradition. Eugene Fields, the Chicago Daily News writer whose “Sharps and Flats” column served as a kind of comedic contemporary history of the city, was delighted by the controversy and roasted Garland in a column that doubled as an invitation for Garland to settle permanently in Chicago. Garland appreciated the publicity, despite its sting, and he saw it as of a piece with a larger trend of literary westering. Francis J. Schulte, a Chicago publisher, had taken one of Garland’s books and was planning to start a “Western” magazine; meanwhile, Garland was in contact with a pair of Harvard undergraduates with family connections in the Chicago newspaper world who were hoping to found a new publishing company, and were signaling that they would like to build a relationship with an experimental writer like Garland. Around the time that company, Stone and Kimball, moved their operations from Cambridge to Chicago, Garland himself moved to Chicago, clearly expecting that Chicago, nature’s metropolis, embodied the nation’s future, and that he might himself become the first great Chicago writer.

For a few years, these relationships worked out brilliantly. Stone and Kimball’s magazine, The Chap-Book, became the most important of the little magazines of the American 1890s, publishing Garland alongside Henry James and H.G. Wells and reaching readers as far away as Paris. Crucially for Garland, they also published a collection of his essays as the 1894 volume Crumbling Idols. Though the essays were not all written in Chicago, the collection was constructed, as it were, toward Chicago, and Garland’s thinking on literature accelerated as he imagined himself as a Chicago writer. A lecture delivered in Chicago became an essay on impressionism, one of the first theorizations of that movement in American art and literary history; an essay on “literary centers” threw down the gauntlet to New York and Boston. In these and other essays in the volume, Garland framed two key ideas that would be foundational for twentieth century writing. The first, a distillation of the problems underlying his short stories, involved a reinterpretation of the meaning of “local color.” Asserting that place was one of the fundamental categories of literary expression, he argued for an overturning of the literary hierarchies that, dating back to such classical modes as the pastoral and the georgic, located provincial and rural writings at the bottom tiers of aesthetic value. He claimed, instead, that because local literatures involved unique forms of local knowledge, they constituted, not hinterlands, but avant-gardes; and he contended that it was through this local writing that American literature connected to the most advanced global writing. Connected to this claim was a second innovation: Garland became the first writer in America to attach the label of “modernism” to the literature he was advocating, and to argue that newness itself was a criterion of literary value. [2]

Brilliant futures require institutions to support them, and as Garland made his way to Chicago he set about the work of building Chicago’s literary public sphere. Even before settling in Chicago, he joined the group of writers and artists who called themselves “The Little Room;” not long thereafter, he teamed up with Chicago sculptor Lorado Taft to found the Central Art Association; and the pair tried again when they worked to found the artists’ retreat at the Eagle’s Nest Art Camp. Later years brought ever-renewed efforts: The Cliff Dwellers Club, the Chicago Theater Society, and the Society of Midland Authors all owed their existence, at least in part, to Garland’s indefatigable enthusiasm. Garland’s longtime friend, the writer Henry Blake Fuller, observed all this activity with amusement, labeling the one-time homesteader a “club carpenter and joiner.” [3] Like Fields’s invitation, Fuller’s characterization had more than a little mockery in it, along with some friendly worry; Fuller was concerned that, with all this organization-building, Garland was squandering energies better directed toward his own creative writing.

Not all the futures imagined in early 1890s Chicago came to pass. The Exposition ran its course; a year later much of the fairgrounds burned; The Chap-Book folded; Stone and Kimball parted ways. By the time the nineteenth century was coming to its end, it was becoming clear that the routes of modernity passed through but did not terminate in Chicago. Garland himself left Chicago in 1916, complaining of how much, in retrospect, he “resented its journalistic trend, its second-rate literary and art criticism, and its insistence on bigness rather than fineness.” [4] At that moment, he probably agreed with Fuller that his efforts on behalf of Chicago had been misspent. But though no one, for at least a decade, took up Garland on his idea of “modernism,” many ideas Garland had brashly labeled “literary prophecies” did, in fact, come true. To a large degree, American modernism would take modernity itself as a measure of literary value; and to a large degree, the most prominent works of American modernism took regional forms. (One thinks, of course, of Faulkner’s “Yoknapatawpha County” or Leon Forrest’s Chicagoan “Forest County,” but also of the submerged and alienated Midwest backgrounds of novels like The Great Gatsby.) And Garland’s Chicago boosterism was probably ingredient to the emergence of these literary futures. All jesting aside, some of the organizations he sponsored still exist today; others, as Garland hoped, played important roles in supporting artists and building readerships and audiences at a formative moment in the early twentieth century.

A case in point: when, in 1912, Harriet Monroe started Poetry magazine, the semi-official journal of American modernism, Garland sent her congratulations and contributed some poems, which she published. But the more significant contribution was in the relationship and the shared background in a civic approach to literature. A friend of Garland’s from Eagle’s Nest circles, she had cultivated alongside other Chicagoan literature lovers a set of assumptions with which Garland agreed entirely: a faith in nature as a source of authenticity, an orientation toward the new, an emphasis on regional particularity, a belief that literature was for everyone but must be advanced by an avant-garde. Though Garland was preparing to leave Chicago around the time Monroe was finally hitting her stride with Poetry—he would become, in his last decades, best known as a gifted memoirist of the Middle Border—her success in building one of the greatest institutions of modernism in the slaughter-house capital of the world owed something to Garland’s contribution of ideas and public efforts. Chicago’s literary club carpenter and joiner had built well.

Christine Holbo is Associate Professor of English at Arizona State University. She is the author of Legal Realisms: The American Novel under Reconstruction.

- Hamlin Garland, My Friendly Contemporaries: A Literary Log (New York: Macmillan, 1932)

- Hamlin Garland, Crumbling Idols: Twelve Essays on Art, Dealing Chiefly with Literature, Painting and the Drama (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960), 81.

- Garland, Companions on the Trail: A Literary Chronicle (New York: Macmillan, 1931), 324.

- Garland, Companions on the Trail, 493.