Five Chicago Baseball Books I Really Like

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

By Donald G. Evans

I have not read nearly all of the Chicago books on baseball. In fact, I own several dozen more than I’ve read, always looking for an opening to move one or more of those onto my nightstand. The insincerity of any “best” list is the insinuation that the author’s opinion is definitive, when in fact it is most often a consensus based on some reading and some scouring of existing reviews. I did some of my own scouring, but limited my list  to the books I know first-hand. The trickiest part of deciding upon my top books revolved around the definition of “Chicago.” The city makes appearances in some truly extraordinary baseball books, like Jimmy Piersall’s and Al Hirshberg’s, Fear Strikes Out (1955), Mark Harris’s Bang the Drum Slowly (1956), and Nicholas Dawidoff’s The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg (1994). Ultimately, though, I decided Chicago’s role in any of those stories was too minor to qualify. Likewise, there are world class books written by Chicago authors, like Thomas Dyja’s Play for a Kingdom, that are not set in Chicago. A book like William Brashler’s The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, which I definitely love, is by a Chicago author and touches upon Chicago. Just not quite enough “Chicago” for my purposes. There are also lots of great Chicago baseball histories and biographies from Eddie Waitkus to Three-Finger Brown, and memoirs from literally hundreds of ex-Chicago stars. I love those, I do. I love the statistics and the voyeuristic peeks at the real people behind the legends, and the unusual, unknown stories. But my short list is the best literature—meaning the best-written of the best stories, books that have lasting value beyond a fan’s curiosity.

to the books I know first-hand. The trickiest part of deciding upon my top books revolved around the definition of “Chicago.” The city makes appearances in some truly extraordinary baseball books, like Jimmy Piersall’s and Al Hirshberg’s, Fear Strikes Out (1955), Mark Harris’s Bang the Drum Slowly (1956), and Nicholas Dawidoff’s The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg (1994). Ultimately, though, I decided Chicago’s role in any of those stories was too minor to qualify. Likewise, there are world class books written by Chicago authors, like Thomas Dyja’s Play for a Kingdom, that are not set in Chicago. A book like William Brashler’s The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, which I definitely love, is by a Chicago author and touches upon Chicago. Just not quite enough “Chicago” for my purposes. There are also lots of great Chicago baseball histories and biographies from Eddie Waitkus to Three-Finger Brown, and memoirs from literally hundreds of ex-Chicago stars. I love those, I do. I love the statistics and the voyeuristic peeks at the real people behind the legends, and the unusual, unknown stories. But my short list is the best literature—meaning the best-written of the best stories, books that have lasting value beyond a fan’s curiosity.

Here are my five, subject to change or expansion.

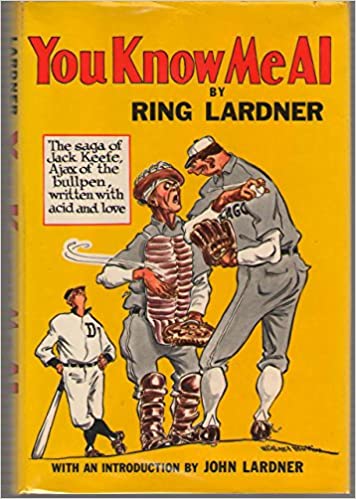

You Know Me, Al, Ring Lardner, Jr. (1914): This epistolary novel is framed as a series of letters from White Sox pitcher Jack Keefe to his friend Al Blanchard back in Bedford, Indiana. The Saturday Evening Post originally published six of these stories before Lardner reimagined them as a larger project. The book’s almost-always dropped subtitled, “A Busher’s Letters” clues you into the nature of the experience. Keefe toggles between the Big Leagues and the Minors, convinced of his star qualities but also desperate to succeed. Colin Fleming, writing in The Atlantic in 2013, called it, “The Greatest Baseball Novel Ever Written.” Lardner brings to bear all his talents in this novel. Lardner was born in 1885, when the first World Series was still 18 years in the future. He worked as a beat reporter when baseball was still young. In addition to his prolific outpouring of baseball coverage, Lardner established himself as a humorist, and eventually carved out a reputation as one of his generation’s best short story writers. For several decades, Lardner ranked as one of the most popular columnists in the country. You Know Me, Al was his only novel. Readers then and now often focus on the humorist bent of the novel, and give high praise to Lardner’s ability to replicate the vernacular of that particular milieu. Virginia Woof, in a contemporary review, highlighted that quality and called Lardner America’s best prose writer. But what distinguishes the novel is the subtle seriousness underpinning the comedy. The conceit of the novel lies both in its framework and its point of view. Keefe tells his story, his way, to his seemingly devoted back-home friend, who remains entirely off stage. The pacing, like a baseball game or perhaps season, is leisurely. It is over the course of many letters that Keefe’s oblivious, braggadocio character gains nuance, and his fatal flaws revealed. This game means everything to Keefe, and he pins all his hopes on it doing for him what it has done for its biggest stars. Money is a constant struggle. Keefe drinks to the point of alcoholism. He gains a lot of weight. He tussles with all of the naysayers, from owners to umpires to reporters to teammates to fans. He gets into fights. He blames his own poor performances on catchers signaling for the wrong pitch and managers using him with a sore arm. He courts women (failed engagements to Hazel and Violet) and eventually marries one (Florence). But his true trajectory does not align with his imagined trajectory and Keefe’s despondency, papered over with increasingly outlandish self-assessments, reaches a suicidal point. While Keefe is a fiction, Lardner uses many real-life players (as well as managers, owners and so forth) as characters throughout the novel, in the process creating a vivid portrait of baseball society. In so doing, Lardner dispels the commonly held notions that baseball players like Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth, much less Keefe himself, are the heroes portrayed in so much sports writing and literature of the time. And while the novel certainly centers on Keefe’s baseball life, it is equally concerned with just plain life. Domestic concerns like planning a honeymoon and finding a rental house, along with all the scuffling to make ends meet, bring into focus a much more complex portrait of Keefe than what seems, at first blush, a caricature. Lardner’s genius is in the way he uses the satirical form to create tension around these rather weighty themes without ever undercutting the wispy, off-hand tone that makes the book so entertaining. When Keefe tries to leverage a leap to the Federal League to renegotiate his contract with owner Charles Comiskey, he winds up essentially jobless and at his wit’s end. He writes to Al that, “I am worried to death…” and concludes that suicide would be the best solution “But I cannot do that Al because I have got no money to buy a gun with.”

Favorite Quote: “He says You been keeping in shape all this winter by trying to drink this town dry and besides that you tried to hold me up for more money when you already had signed a contract already and so I was going to send you to Milwaukee and learn you something and besides you tried to go with the Federal League but they would not take you because they was scared to. I don’t know where they found out all that stuff at Al and besides he was wrong when he says I was drinking to much because they is nobody that can drink more than me and not be effected.”

Three Strikes, You’re Dead, Robert Goldsborough (2005): This noirish crime novel, the first in a series featuring Chicago Tribune reporter Snap Malek, uses Chicago baseball as the major sub-plot. Snap, a recovering alcoholic who lives in a three-room apartment just south of Wrigley Field, investigates the assassination of Chicago mayoral candidate, Lloyd Martingdale. The Republican had promised, as his major platform, to eradicate organized crime from the city, making the Democratic Party and the Mob prime suspects.

Malek, uses Chicago baseball as the major sub-plot. Snap, a recovering alcoholic who lives in a three-room apartment just south of Wrigley Field, investigates the assassination of Chicago mayoral candidate, Lloyd Martingdale. The Republican had promised, as his major platform, to eradicate organized crime from the city, making the Democratic Party and the Mob prime suspects.

Steve Malek gets his nickname because of the signature snap-brimmed fedoras he wears, and right there you get an impression of his character. Snap is a street smart, savvy reporter cut from the same cloth as the classic gumshoes, but heavier on wit than muscle. Snap sniffs out clue after clue, and in defiance of editorial dictates, pursues leads that take him to the feet of a rough-and-tumble Chicago Outfit crowd. He is Chicago smart, able to leverage connections all over the city, but especially in the Homicide Bureau, to get him closer to the truth than anybody else.

The Cubs, just prior to the 1938 season, land Dizzy Dean, the all-star right-hander who’d pitched for the St. Louis Cardinals in his first seven seasons, including three 20 and one 30-win campaigns. The trade improves the Cubs’ chances to win the NL pennant and possibly the World Series, but more than that Dizzy factors in the mystery at hand. Dean develops the habit of dropping into a North Side bar for the occasional beer. The owner proudly displays a signed Dizzy Dean baseball behind his bar, a baseball that eventually becomes a weapon used to thwart the bad guys from snuffing out Snap and his investigation. Snap is a lifelong, die hard Cub fan, and the pace of his life, and thus the novel, parallels that of the baseball season.

Snap is in attendance at the famous Homer in the Gloamin’ game, as well as the second 1938 World Series game against the Yankees. Part of Goldsborough’s technique, of course, is to place his protagonist in proximity to these sorts of historic events and people as an occasion to explode their possibilities. Thus, readers get a street level view of Gabby Hartnett launching a two-out, 0-2 pitch into the center field bleachers at a dark Wrigley Field to overtake the Pirates for first place. The novel also roams into the Cubs’ locker room, and at one point Snap even gets a ride from outfielder Augie Galan.

Goldsborough is a consummate craftsman, especially adept at plot and character building. He cut his teeth during a long journalism career that included almost a quarter century each at the Chicago Tribune and Advertising Age. More so, Goldsborough established a literary career when he picked up the writing of the Nero Wolfe mysteries where creator Rex Stout had left off. Goldsborough is a giddy historical buff, especially as it pertains to Chicago. Goldsborough’s lived experience as a reporter combined with his joyful regard for Chicago history and true reverence for the genre result in a highly rewarding novel. In addition to the Cubs players that make cameos in the novel, historical characters like Helen Hayes and Al Capone zip in and out. News of the day informs the action. All of that is incredibly rewarding to the reader, but the pulse of this novel (and the subsequent titles in the series) is the protagonist.

Favorite Quote: “Now, for the last two years, I’d had a taste of what I felt was the real Chicago: North Clark Street. If any thoroughfare throbbed to the rhythms of the city, this was it. I hated living alone, but at the same time, I loved Clark Street.”

Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series, Eliot Asinof (1963): Asinof’s definitive book on the most storied baseball scandal of the 20th century is a reconstruction of events that takes liberty with available facts. The author’s novelistic approach adds suspense and intrigue impossible in a straight non-fiction telling. But Asinof’s gift is how seamlessly he blends all the disparate parts, sprinkling the history of baseball gambling with an anecdote about rowdy White Sox players on the road, with portraits of dozens of minor and major figures, with atmospheric detail about the cities and era in question.

Favorite Quote: “Chicagoans, like the rest of America, in September, 1919, wanted to be carefree. Hadn’t they earned that right? With the end of the war, they expected the end of all responsibility. They were fed up with humanitarianism, liberalism, do-goodism. The word was out: have fun!”

Bleacher Bums, Joe Mantegna (1977): Not a book, I know, but the script for this play is incredible. I first saw this play in the late 1980s at the  Organic Theatre on Clark Street, near Wrigley Field. By then, it had become one of Chicago’s most cherished local plays. The play is set in the summer of 1977, smack dab in the middle of the Wrigley Field bleachers. The ensemble cast includes a plethora of colorful fanatics—degenerative gamblers, every last one. There is the blind man who listens to his transistor radio and does his own play-by-play. The guy who always bets (and wins) against the Cubs. The guy who always bets (and loses) on the Cubs. The nagging but incredibly informed wife. The gorgeous sunbather. This script arose out of a Second City, improv mentality. In the original production, Dennis Franz played Zig, and along the way notables such as George Wendt have anchored the cast. Do not confuse this, though, with a David Mamet play. It is what the (also never used) subtitle suggests: “A Nine-Inning Comedy.” There is no plot worth mentioning. It is a day of drinking, cigar smoking, gambling, bickering, cheering, booing, and what you get is a fun two hours that ultimately doesn’t change your life. Like baseball itself.

Organic Theatre on Clark Street, near Wrigley Field. By then, it had become one of Chicago’s most cherished local plays. The play is set in the summer of 1977, smack dab in the middle of the Wrigley Field bleachers. The ensemble cast includes a plethora of colorful fanatics—degenerative gamblers, every last one. There is the blind man who listens to his transistor radio and does his own play-by-play. The guy who always bets (and wins) against the Cubs. The guy who always bets (and loses) on the Cubs. The nagging but incredibly informed wife. The gorgeous sunbather. This script arose out of a Second City, improv mentality. In the original production, Dennis Franz played Zig, and along the way notables such as George Wendt have anchored the cast. Do not confuse this, though, with a David Mamet play. It is what the (also never used) subtitle suggests: “A Nine-Inning Comedy.” There is no plot worth mentioning. It is a day of drinking, cigar smoking, gambling, bickering, cheering, booing, and what you get is a fun two hours that ultimately doesn’t change your life. Like baseball itself.

Favorite Quote: “Hey, you guys, I want a beer. You want a beer? Does somebody want a beer? How ‘bout a beer?”

My Baseball Diary, James T. Farrell (1957): The young James T. Farrell was a baseball nut, and those formative years cemented a lifelong attachment to the game. He would cover many baseball stories as a reporter and use the sport in a variety of short stories and novels. This memoir takes us through Farrell’s life, from experiences that begin around 1911, in his seventh year, and meander their way into the early 1950s. Farrell writes about eyewitness accounts of major stars and significant games, but his recollections do not bog down in Big League history.

As a youth, Farrell played the game religiously and fanatically, in his backyard, at South Side parks, against the wall, all the while obsessively attending not only Major League games but semi-pro and recreational contests in which older, more experienced players served as idols. In between reminiscences (often in the teens, twenties and thirties), Farrell includes short story and novel excerpts featuring his childhood alter ego Danny. In laying these memories side-by-side with his fiction, we get to see how one of the 20th century’s best writers converted his experiences into literature. This memoir is not for a general audience, but rather real baseball lovers and perhaps Farrell fans. It is nostalgic. At times graceless. The prose is certainly not on par with Farrell’s finest work, and in fact at times seems hurried. But the reminiscences are peppered with lively details from a forgotten era, captured as an eyewitness. There are the horse and wagons interrupting play, the term “swift pitching,” the megaphone used to announce player changes. Even when Farrell talks about historical realities of the game, such as a catcher for the first time wearing shin guards, it is as a first-hand observer, a fan who’d lived through the old ways and into the new. What arises from Farrell’s memories is a portrait of a baseball world that we will never again see, in part because though players might have been heros they were not celebrities. As a boy, Farrell recalls riding the streetcar with players. Some of the players remembered his name. Once, he wound up sitting in the visitor’s dugout at White Sox Park on a chilly August day with players watching over and doting on him, offering him a sweater and checking to make sure he was warm enough. For Farrell, it was a family affair that involved his uncles and his grandmother and his brother, and though a White Sox fan he hunted down games at West Side Park and all through the city. It was also a neighborhood affair, and Farrell writes about Washington Park players like Fred Lindstrom that rose through their ranks to Big League success. Farrell spends a lot of time going over his boyhood recollections of the game and the way those early memories shaped his adult passion for the game. Eventually, the book segues into a time in which Farrell, as a sports journalist and then major literary figure, had a different kind of access to the game and its players. What Farrell seems to understand is that the periphery of the game IS the game—without it, the pro product would be lifeless. My favorite parts of this memoir are when Farrell takes us through the experience of finally playing on a team with a uniform, and profiles the woman across from old Sox Park who through kindness and an open-door policy built a devoted community that included legends like Babe Ruth. All the bits and pieces, like his essay on scouts, add up to a much greater whole.

Favorite Quote: “This long wait was an adventure rather than a boring experience. These strange men standing in line, sitting on boxes, squatting by a fire, playing poker, chatting intermittently about the weather, shivering a bit as I did—they and I were bound by a common passion.”

Donald G. Evans is the Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. He is the author of a novel and short story collection, and editor of an anthology. His personal blog often explores Chicago literature, including a recent post about Thursday night’s Chicago (Baseball) Classics program.