Don De Grazia (January 3, 1968-June 13, 2024)

Friday, June 21, 2024

by Donald G. Evans

Chicago means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. It’s personal, how you think about it. We mentally form a composite sketch that includes iconic buildings, beloved restaurants and bars, L stops, historical events, places where we grew up or grew old, memories. We populate our own Chicago with people that make it home—sports stars and celebrities, sure, but mostly family and friends, colleagues, acquaintances, even strangers we’ve encountered. These are not places and people we necessarily visit on a regular basis—in some cases, it’s been years. But Chicago is Chicago because they are here.

Don, Siera & Daisy at The Beat Kitchen last December.

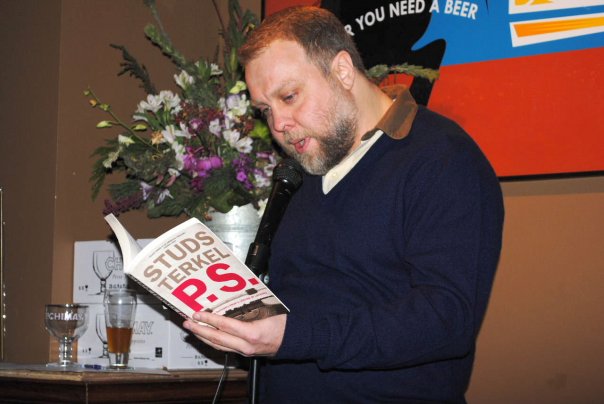

Also pictured: Don Evans, Toya Wolfe, Billy Lombardo, Anna

Jung, and Donna Montgomery. (Photo by Amy Danzer).

Don De Grazia is no longer here. Our city is smaller and more ordinary without him. Don died last Thursday night playing for his beloved Lee Elia Experience softball team. They were going for the championship—they GOT the championship. And then, just after the game, at age 56, he died, like a strange twist in one of his own stories. I say twist, because it’s not an ending. Like Marshall Fields or Mike Royko, Don made such giant contributions to Chicago’s life and culture that we’ll always think of him as still a part of us.

By virtue of his debut novel, American Skin, Don De Grazia claimed immortality. The word “masterpiece” is often abused—those of us who respect the word use it sparingly. There are many, many great books, but very few of those ascend to this rare class of literature. A masterpiece, in my definition, is transcendent. A masterpiece compels its reader to examine and reexamine their life, take inventory of their values, and look at the world just a bit differently. A masterpiece makes you feel. A masterpiece, from beginning to end, vibrates with a tension that insists you see this story through. A masterpiece changes you, maybe for an instant, maybe forever. A masterpiece has unlimited shelf life—read it on its launch date or twenty years later, and it will resurrect your senses.

American Skin is a masterpiece. Told from the point of view of Alex Verdi, the novel takes on the large, unwieldy issue of race relations in America. But to reduce it to that does the novel injustice. It’s a coming-of-age story that breaks the mold. Orphaned at 17 when his parents get jailed for drug possession, Alex flees his manufactured rural existence for the big city. He believes, based on a newspaper article, that his own freedom is in jeopardy. At his core, Alex desires family and purpose. He wants friendship and love. He relishes safety. Like notable Chicago novels from the early 20th century, such as Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, this migration from the hinterlands to Chicago represents a dramatic life change. Unlike those novels, American Skin’s protagonist makes this shift almost entirely without deliberation. Alex would gladly return to his old life if it hadn’t literally and figuratively burned to the ground. Young and naïve, Alex’s choices—though they hardly seem conscious—are predicated on survival. His dreams, when they come, gravitate toward the ridiculous.

Before Alex encounters a group of skinheads, most notably the charismatic and legendary leader Tim Penn, he is alone. He goes from his factory job back to his YMCA room, his YMCA room back to his factory job, a life devoid of satisfaction or intimacy and fraught with danger. Again, survival is the best he can hope for, though he drifts into thoughts of more. He wants to return to his family a great man. The skinheads in essence adopt Alex—they protect him--and in the process expose him to a community on perpetual high tilt, a landscape of violence, lust, decadence, sweat, and youth. These young people, though, already operate as adults, or as though they’ve achieved a certain wisdom that defies the stupid conventions put in place without their consent. Unlike his solitary YMCA room, Alex finds himself crowded with life—at one point, at the club where he works and stays, he dives into a pile of bodies before being lifted and passed around.

The novel is divided into four parts. From The Gorgon and his skinhead cronies, Alex goes—by court order—into basic training for a reserve military appointment. Then onto Evanston, and an attempt to be admitted into Northwestern University and gain acceptance among this presumably higher class of people. Finally, prison. Race is a through line, as is class. So is the idea of justice. The narrative arc—skinhead to military to university campus to prison—makes perfect sense, almost an inevitability, within the context of this fictional universe. This is a story in which the protagonist searches everywhere for answers—libertarian novelists, Buddhist priestesses, yuppie women, mobsters, extremist cults, literature, gangs…somebody must know something that will lift him into a higher plain of existence. It is in large part Alex’s searching that makes him a compassionate and likeable character. Alex’s stark flaws and grievous mistakes, in Don’s hands, do not make him despicable. They make him human. Don’s major accomplishment with Alex Verdi is that we readers, no matter what our station, identify with such an aggressively unheroic character,

onto Evanston, and an attempt to be admitted into Northwestern University and gain acceptance among this presumably higher class of people. Finally, prison. Race is a through line, as is class. So is the idea of justice. The narrative arc—skinhead to military to university campus to prison—makes perfect sense, almost an inevitability, within the context of this fictional universe. This is a story in which the protagonist searches everywhere for answers—libertarian novelists, Buddhist priestesses, yuppie women, mobsters, extremist cults, literature, gangs…somebody must know something that will lift him into a higher plain of existence. It is in large part Alex’s searching that makes him a compassionate and likeable character. Alex’s stark flaws and grievous mistakes, in Don’s hands, do not make him despicable. They make him human. Don’s major accomplishment with Alex Verdi is that we readers, no matter what our station, identify with such an aggressively unheroic character,

This is a story that Don alone was qualified to tell. Don leveraged his considerable gifts and unique access to bring readers to places no other writer could or would go. Don was keenly intelligent in the way of a lot of writers—incredibly well read and informed—and also super smart on a street level—he knew, from experience, how things were. I once told Don about a conflict I was having with a mutual acquaintance—nothing serious, but something that bothered me. Don paused only a second before declaring, “Fuck that guy. He’s not only an asshole but a shitty writer.” I knew instantly Don was right and I stopped caring.

In American Skin, through his narrator, Don writes, “It occurred to me that people have a hard time expressing themselves, so they slap together bits and pieces of advertising slogans and soap-opera dialogue and Ann Landers advice columns and whatever, and, armed with that, they try and get as close as they can.” Not Don De Grazia. Not in American Skin, or in any of his other brilliant writing. Don found his way, through words, to the essence of experience. He captured key moments. He discovered the truth hidden among all the lies.

In Chicago, you’ll hear people say, “Great guy.” It’s an example of people having a hard time expressing themselves. It’s a kind of shorthand, but when you hear it you know what it means. Don was the embodiment of a “great guy.” You had to earn Don’s loyalty. He admired talent and respected hard work. He noticed selflessness. He believed in kindness, as well as bluntness. Once you had his loyalty, Don took it upon himself to help in every way possible.

Don was a long-time professor at Columbia College, and during the course of his teaching career mentored hundreds of creative writing students. Many, no doubt, came to Columbia College after reading American Skin. Sydney Richardson summarizes his academic career for The Columbia Chronicle. Over the years, Don recommended his students for several publications to which I was attached. He spoke with great respect and admiration for so many deserving young artists. He freely contributed his talents to countless upstart journals (such as The Great Lakes Review), live lit initiatives like Windy City Story Slam, and other creative projects. He was an instrumental part of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame family—from the very start and until his very end, Don volunteered for or agreed to speak, write, promote, and generally pitch in. “Whatever you need,” he told me all the time. He also started a bunch of his own enterprises, as well, incredible literary series like Ex Libris at Soho House and Come Home Chicago at Underground Wunderbar. In all of these endeavors, Don was driven to explore and celebrate great literature--especially Chicago literature--and to give other writers a platform. In short, Chicago (and beyond) benefitted from Don’s enormous talent, energy, and generosity. We were lucky to have Don for as long as we did and lucky to have all he leaves behind.

Alex, under the influence of Ayn Rand, told his Lake Forest College girlfriend, “Our brains are too small to understand that it’s no big deal to die—that dying is just like growing up. Nothing ever ends.”

Services for Don are this Saturday, June 22, 1-3 p.m. at Simkins Funeral Home, 6251 Dempster, Morton Grove, IL. A memorial visitation for family and friends will be held from one p.m. until time of service at three p.m. with a Celebration of Life to be held at a later date. In lieu of flowers, donations to a Go Fund Me account for Daisy would be appreciated. Cremation held privately.

will be held from one p.m. until time of service at three p.m. with a Celebration of Life to be held at a later date. In lieu of flowers, donations to a Go Fund Me account for Daisy would be appreciated. Cremation held privately.

Donald G. Evans is the Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.