Director Rana Segal and Author Michelle Duster on the Ida B. Wells Monument and the Documentary of its Making

Monday, October 21, 2024

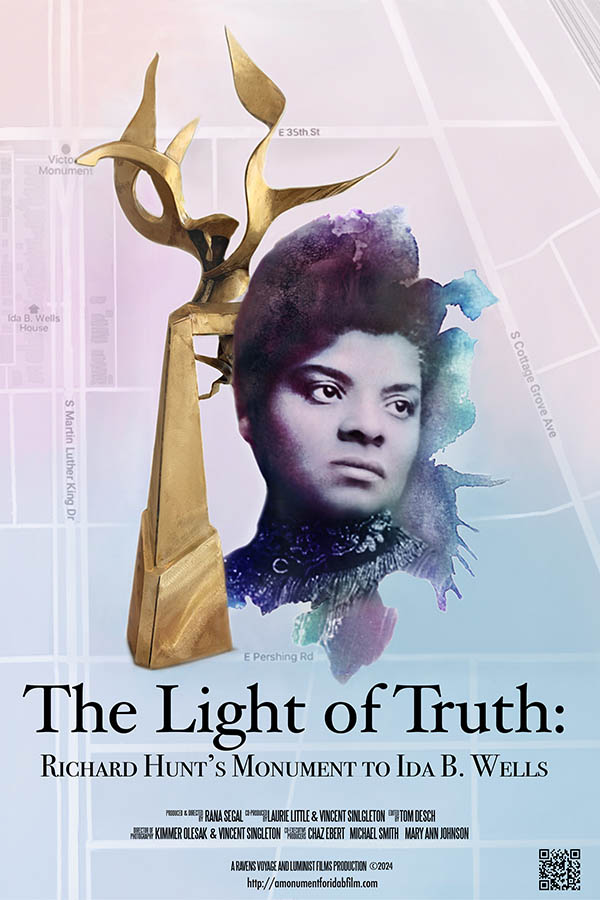

Director Rana Segal’s documentary The Light of Truth: Richard Hunt’s Monument to Ida B. Wells will be screened on Sunday, October 27 as part of the 60th Chicago International Film Festival. The 66-minute film will be shown at the Chicago History Museum, starting at noon. According to the festival’s notice, the film “weaves together Hunt’s story with the captivating history of his subject, Ida B. Wells. In connecting artist and activist through Hunt’s towering 35-foot-high Bronzeville-based sculpture, the film reveals their analogous missions to battle racism and forge new paths for Black Americans.” Michelle Duster was a significant force behind the sculpture commission and eventual installation at the site of the Ida B. Wells Homes, which were named after her foremother. For Segal, this is her second documentary treatment of a sculpture project honoring an iconic Chicago author; her 2019 film, Gwendolyn Brooks: The Oracle of Bronzeville, traces sculptor Margot McMahon’s creation of the poet’s portrait that was ultimately installed in Gwendolyn Brooks Park. In addition to many articles and public programs, Duster has written biographies of Ida B. Wells, a children’s picture book, Ida B. Wells, Voice Of Truth: Educator, Feminist, and Anti-Lynching Civil Rights Leader (2022) and an adult book, Ida B. the Queen (2021).

Director Rana Segal’s documentary The Light of Truth: Richard Hunt’s Monument to Ida B. Wells will be screened on Sunday, October 27 as part of the 60th Chicago International Film Festival. The 66-minute film will be shown at the Chicago History Museum, starting at noon. According to the festival’s notice, the film “weaves together Hunt’s story with the captivating history of his subject, Ida B. Wells. In connecting artist and activist through Hunt’s towering 35-foot-high Bronzeville-based sculpture, the film reveals their analogous missions to battle racism and forge new paths for Black Americans.” Michelle Duster was a significant force behind the sculpture commission and eventual installation at the site of the Ida B. Wells Homes, which were named after her foremother. For Segal, this is her second documentary treatment of a sculpture project honoring an iconic Chicago author; her 2019 film, Gwendolyn Brooks: The Oracle of Bronzeville, traces sculptor Margot McMahon’s creation of the poet’s portrait that was ultimately installed in Gwendolyn Brooks Park. In addition to many articles and public programs, Duster has written biographies of Ida B. Wells, a children’s picture book, Ida B. Wells, Voice Of Truth: Educator, Feminist, and Anti-Lynching Civil Rights Leader (2022) and an adult book, Ida B. the Queen (2021).

DGE: The Light of Truth: Richard Hunt’s Monument to Ida B. Wells is a documentary equal parts about Wells and the making of a sculpture dedicated to her legacy. The occasion of this sculpture creation acts as a portal into the life of Wells. How did you balance these two narratives?

RS: That was the tricky part; I didn’t know if it would work. I wanted the through line to be the making of the sculpture, from the very beginning to the dedication: the actual welding it together, the installation, then the dedication. I wanted to show all of that. I also wanted to tell Ida’s story, but of course she had an amazing life, so I had to pick out the most critical parts: her origin story, how she became a journalist, how she dealt with racism, why did she get involved in the anti-lynching movement, and then her migration to the Chicago area and her suffrage work. It took a while to see which sections of Richard’s life I would include. In order to keep it down to 56 minutes for television, we didn’t put in the part about Emmett Till. When we finally did put that in, you looked at Richard Hunt differently. When he attended the Emmett Till funeral, it changed his way of looking at his own work, because I believe it gave him more of a purpose. He was dealing with racism in his own way through his sculptures.

DGE: So you started with a framework and then looked for opportunities to weave the two stories together. Okay. Let’s go way back. Michelle, as Wells’s great-granddaughter, you’re uniquely qualified to protect and promote her legacy. You’ve worked tirelessly, even long before this sculpture project, to create awareness about Ida B. Wells’s contributions to American society. The completion and installation of the statue is a crowning achievement in your own efforts to recognize your great-grandmother. Take us back to the start of this process. What inspired the project?

MD: In the early 2000s my family was aware that the city was tearing down the Ida B. Wells Homes in their Plan for Transformation. The housing community had been a staple in the Bronzeville neighborhood for over 60 years, starting in 1941. We strongly felt that our ancestor’s name should not be forgotten with the disappearance of the buildings that were named after her. I had already started my quest to make her writings more available to the general public, and had edited and published two books with her original writings: Ida In Her Own Words (2008) and Ida From Abroad (2010). My father encouraged me to contact the mayor’s office to request that the city honor Ida as a significant historical woman, which was separate from the housing community that bore her name. Mayor Richard M. Daley responded informing us of a committee that had been formed regarding a project to honor her. Once we connected with the committee, in 2008 we were asked to join and represent the family.

DGE: When did you first start raising money? How did it come about that Richard Hunt was chosen and accepted the commission?

MD: Richard Hunt was the committee’s first choice for the artist to do the work once we made the decision to have an abstract monument created. We approached him about the idea and he agreed to do it. We felt he was the best choice because he was a native Chicagoan, was familiar with the neighborhood and its history, and his lived experience would add to the project in ways that could not be substituted through merely reading about it.

Once Hunt agreed to do the project, he provided a proposal and budget. After we knew the numbers we created a strategy to raise the money. We had a fundraising kick-off event in early 2011. Over the years we hosted several fundraising events for the arts community and neighborhood community. Due to various changes in the committee over time, after seven years we had raised about a third of the original budget. I started getting concerned about our ability to meet our goal in a timely fashion with the strategies used to that point. In 2018, The New York Times included Ida B. Wells in their Overlooked series, which raised national awareness of her legacy. I decided to leverage that attention and use an unconventional strategy of taking the project directly to a national public by way of Twitter. My efforts caught the attention of several people with large online platforms who uplifted the project. As a result, several thousand people contributed and all of the remaining money needed from the initial budget was raised in four months.

DGE: Rana, there is a relationship between Richard Hunt’s artistic choices as a sculptor and your artistic choices as a filmmaker. Can you share some insight into how the story told through this documentary took shape?

insight into how the story told through this documentary took shape?

RS: Many of Richard’s pieces have stairways; Jacob’s Ladder, for instance. Martin Luther King has a bit of a staircase. Another piece of John Jones was just discovered; the missing part that went with it was a stairway. The stairways and steps represent lifting as we climb, which is a phrase in African American culture. That was the reason Richard was putting in the stairway [in the Ida B. Wells monument]. The stairway is metaphorical for always bringing people with us as we rise. The thing about what I’m trying to do in this film is tell the story of these two amazing people. A lot of people don’t know their history. The film is trying to uncover their truth and tell the world. It’s important in these times that we lift these people up.

DGE: Michelle, you’re an accomplished author and historian in your own right. What role did you play in this documentary film project, in particular the story structure?

MD: I honestly did not have any direct input into the story structure of the film. I simply kept Rana informed of the various activities and events I was engaged in and she chose to film many of them in order to have a multi-dimensional perspective of who both Ida and Richard were.

DGE: Richard Hunt was born on Chicago’s South Side, studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and rose to prominence as one of America’s most important sculptors. In particular, Hunt made a reputation as a brilliant abstract artist and counted among his many accomplishments a series of celebrated public sculptures. The setting for his story, like that of Wells, is Chicago’s South Side. Both are internationally renowned figures, but I wonder what part Chicago plays in this film.

RS: Even though they lived in separate eras, both Ida and Richard decided that Chicago was important to their lives and careers. Ida met her husband at the Columbian Exposition. She ended up moving to Chicago, building her home with her husband here, as well as her business as a journalist and civil rights activist. Richard Hunt was well known in the art world, but chose to stay; he decided he didn’t want to be in New York or L.A. or London because he loved Chicago. Richard felt as if he could do whatever he wanted to in Chicago. The city also gave Ida opportunities she might not have gotten elsewhere, like working with white women during the suffrage movement.

MD: I think the role Chicago plays in the film is that of highlighting the neighborhood of Bronzeville, where many settled during the first wave of the Great Migration, which was also where the Ida B. Wells Homes were located. Several former residents of the Homes were interviewed and included in the film. Their experience living in the housing community tells a perspective on life in a section of the South Side of Chicago during a certain period of time.

DGE: Abstract. That’s what Hunt did. So you knew from the start that this would not be a portrait; it would not be like most such monuments. Why was this the right choice?

MD: As a committee we made a decision to allow people to bring themselves to the artwork and interpret Ida’s life from their own perspectives. We felt this was an important way to capture Ida B. Wells because as a pioneering journalist, suffragist and civil rights activist who founded several organizations, she was a very multi-faceted person. She was also a mother and wife. So when people look at the sculpture from different angles they can see representation of her life in different ways. The panels with her images, quotes, and short bio make it possible to see and learn about different periods of her life.

DGE: For me, the most powerful scene—so vividly captured and rendered on film—was the installation. This crane moves enormous pieces as the artist fusses over their exact placement. We get a sense of the size and scope of this sculpture—the weight alone is daunting. We also realize its permanence—once this hulking metal artwork is placed, there’s no going back. What scenes or shots were your favorites?

DGE: For me, the most powerful scene—so vividly captured and rendered on film—was the installation. This crane moves enormous pieces as the artist fusses over their exact placement. We get a sense of the size and scope of this sculpture—the weight alone is daunting. We also realize its permanence—once this hulking metal artwork is placed, there’s no going back. What scenes or shots were your favorites?

RS: I loved the train scene; it’s horrifying, but that really showed who Ida was. She wasn’t going to take any gruff. She was a fighter from the beginning to the end of her life; that really is why she is such a hero and a trailblazer. She was one of the first African American women to be fighting for such a cause, and she was so young when she was doing it. I really like that scene.

MD: For me, it was watching Richard Hunt as his work was installed. It was such a long journey to get the work done, and he had gotten sick in the later years of the project. The fact that he recovered and was able to finish and see his work completed was very touching.

DGE: Is the film another way in which this sculpture, and by proxy Ida B. Wells and Richard Hunt’s legacies, gains permanence?

RS: The sculpture will be around for a long, long time; hopefully the film will be around for a while, too. I would like it to be. I hope it’s an educational tool.

MD: Yes. I felt it was important to capture the process of getting this piece done as both a way to chronicle Richard Hunt as a premier sculptor, but also to show how countries can honor their leaders through public art tributes. Ida B. Wells was a woman who had a housing community named after her. After the buildings were torn down, the woman Ida B. Wells still needed to be remembered and honored. Having the first, and still only, monument to an African American woman in Chicago and one of the few in the country dedicated to Ida B. Wells is something very important to capture in our country’s history.

DGE: Richard Hunt passed away on December 16, 2023. Was he able to see the film before his death? What were his reactions?

MD: I was involved in organizing a 2nd Annual Ida B. Wells Festival in Bronzeville in June 2023. We decided to host a screening of the film [at Northeastern Illinois University] as part of the festival and luckily Richard Hunt was able to attend the event. It was beautiful because he not only saw the film, but he received love and appreciation from the audience who were very excited and happy to meet and take pictures with him after the post-screening panel.

festival and luckily Richard Hunt was able to attend the event. It was beautiful because he not only saw the film, but he received love and appreciation from the audience who were very excited and happy to meet and take pictures with him after the post-screening panel.

RS: It was amazing he could make it. He did say he liked the film; I was happy about that. We had a lot of cast and crew there. It was lovely to see him there for that.

DGE: In light of Hunt’s passing, how important is it that the film also documents his work process? Did his passing at all alter your approach to the final editing?

RS: I’m really happy we were able to document his process. It shows a master at work, involved with the passion of his life. Wouldn’t it be great if we had that for Leonardo da Vinci and some others? His passing did not change the way we were going to edit the film.

DGE: I was lucky to play a very tiny role in the filming of this documentary. Rana, you had gotten permission to film at the Monticello Railway Museum on a day it was closed. You needed a bunch of real actors, as well as an old white guy to play the train conductor—that was me. There were also a bunch of extras. It gave me a chance to see the enormous time and cost involved in capturing footage for a documentary like yours. Some twenty or thirty people traveled from Chicago, stayed a day or two at a local hotel, had to be fed, and so forth. We spent most of the day in Monticello. When I first saw the film screened at Dominican University, it surprised me that the entire effort produced a few minutes of actual film. Tell me about the challenges of being an independent filmmaker and how you overcome all the obstacles, financial and otherwise, to capturing such telling, beautiful scenes?

RS: I filmed in Pasadena during the Rose Bowl Parade. There was a float dedicated to the 100th anniversary celebrating suffrage. Michelle represented Ida B. Wells. They had the Statue of Liberty all made out of flowers. Michelle had a suffrage banner on her, and there were over 100 women dressed as suffragists following the float. That’s how we started. Then lockdown came a month later. It was really hard to figure out how to raise money. Basically, during covid, I was in a bubble with Richard and Eric Stephenson, his studio manager. David, his studio assistant, was there, and Gwen Yen Chiu. I would go almost every day into Richard’s studio on Lill [Avenue], Lill and Sheffield, and film what they were doing.

Ida B. Wells. They had the Statue of Liberty all made out of flowers. Michelle had a suffrage banner on her, and there were over 100 women dressed as suffragists following the float. That’s how we started. Then lockdown came a month later. It was really hard to figure out how to raise money. Basically, during covid, I was in a bubble with Richard and Eric Stephenson, his studio manager. David, his studio assistant, was there, and Gwen Yen Chiu. I would go almost every day into Richard’s studio on Lill [Avenue], Lill and Sheffield, and film what they were doing.

It was going to cost $10,000 just to do the train scene at the [Illinois] Railway Museum in Union, Illinois. That was just out of our ballpark; we could not afford it. We tried doing stills. We were going to do drawings, but that didn’t quite work. We knew that if we were going to do that scene, we had to do live action. Then we were able to find the perfect train [museum] that would let us film for a reasonable amount of money. Also, a donor came through to give us the money to finish that scene. We were able to get all the costumes, all the extras, the conductor, the actress who was playing Ida…I was shocked it all came together in such a short amount of time; we had it in the film just three weeks later.

DGE: “Rana Segal, Director” naturally and rightfully gets the main credit. But there were many others without whom this project doesn’t happen, I’m sure.

RS: There’s a billion people, I had a co-producer, Laurie Little, and then Vincent Singleton was a co-producer and also one of the camera people and one of the people that did the drone camera. Eric Stephenson did most of the drone work; he did a beautiful job. Kimmer Olesak was the main camera person, besides myself. Tom Desch was one of the editors. We had a lot of great actors. Cat Evans, when we found her we were blown away because she looked so much like Ida and she was perfect for the part. It was a passion project, that’s what we like to say. We put a lot of blood, sweat and tears into it. We also felt Ida was kind of on our shoulders helping guide us in a lot of our choices.

DGE: Michelle, the work you’ve done on behalf of your great-grandmother is ongoing. People forget, right? Or they don’t know in the first place. This documentary is another way that you’ve brought attention to Wells’s work. What is the importance of this in the overall fabric of what you’ve done and are doing?

documentary is another way that you’ve brought attention to Wells’s work. What is the importance of this in the overall fabric of what you’ve done and are doing?

MD: I realize that people learn in different ways, so having information about the work of my great-grandmother in the form of a film is important. It complements the various other projects which include a Barbie doll, the monument itself, historical markers, books, articles, street names, and a quarter which will be issued by the US Mint in 2025.

DGE: There is a certain amount of prestige that accompanies a screening at the Chicago International Film Festival. It validates, to many, the quality and importance of the documentary. It also means more viewers. What can we expect when we attend the October 27 screening? What does this mean for the film in the bigger picture?

RS: Hopefully, it will get wider viewership around the country, get it into the educational market, and maybe we’ll be able to get it on Channel 11. We have already gotten people interested from other PBS stations. We’re going to have a panel there at the Chicago History Museum with Dan Duster, great-grandson of Ida B. Wells; Jon Ott, Richard Hunt's official biographer; and Eric Stephenson.

MD: The more exposure people have to the lives of both my great-grandmother Ida B. Wells and Richard Hunt, the better. I strongly feel that the contributions African Americans have made to this country need more attention. Both Wells and Hunt were trailblazers, albeit in different professions and time periods. But their lives illustrate a continuum of the African American experience and are important testaments to how having convictions, vision, and tenacity can break barriers for others to follow and succeed.

DGE: Thanks and congratulations to you both. I look forward to seeing the film again at the Chicago History Museum.

Donald G. Evans is the author of a novel and story collection, as well as the editor of two anthologies of Chicago literature, most recently Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry. He is the Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.