Ana Castillo’s My Book of the Dead

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

Almost from the start of her education at Little Italy grade schools and then Jones College Prep, Ana Castillo refused to limit herself to one thing or another. Growing up in a politically-charged Chicago, Castillo witnessed the near-demolition of her family’s neighborhood, Martin Luther King, Jr. in Marquette Park, the Democratic Convention riots, and so much more that sparked her interest in social justice, especially as “a brown girl.”

Almost from the start of her education at Little Italy grade schools and then Jones College Prep, Ana Castillo refused to limit herself to one thing or another. Growing up in a politically-charged Chicago, Castillo witnessed the near-demolition of her family’s neighborhood, Martin Luther King, Jr. in Marquette Park, the Democratic Convention riots, and so much more that sparked her interest in social justice, especially as “a brown girl.”

She earned a BS in art with a minor in secondary education, then went on to complete an MA in Latin American Studies and a PHD in American Studies. She even thought seriously about going into international law because of her deep interest in participating in some sort of social change.

Likewise, her literary output has been wide-ranging, with publications that include distinguished poetry, novels, memoirs, essays, and criticism. Though Castillo did not fully appreciate the fact until she was a published author, writing came easily to her, and soon it became her number one pursuit. It became her preferred and most powerful mode of activism.

The Mixquiahuala Letters (1986), her first of five novels, won the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation. So Far from God (1993) earned widespread praise, including a New York Times Notable Book of the Year citation and a Barbara Kingsolver Los Angeles Times Book Review rave. Peel My Love Like an Onion (1999), a Chicago story about a disabled Chicana flamenco dancer at a crossroads far from her glorious youth as a famed artist, achieved critical and commercial acclaim.

Castillo has been labeled a feminist, scholar, Chicana, Indian, activist, even eroticist. Her work has been linked to a host of literary schools, including post-modernism and magical realism. For some, Castillo is considered a controversial figure, but she points out that “we’re all controversial.”

Labels, of course, are a way to pinpoint an audience, to reduce a writer to that which is easily understandable. Castillo’s success as an artist and educator defies such attempts at reductivism; in fact, her literary vagrancy keys that success.

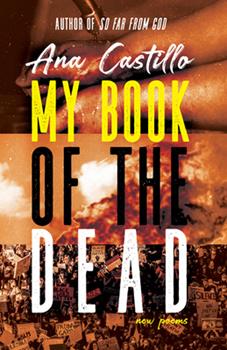

The Chicago native’s latest title, My Book of the Dead, is her fifth poetry collection, following well-received offerings such as My Father Was a Toltec 1995) and I Ask the Impossible (2001).

My Book of the Dead is, as the title suggests, a meditation on mortality, but not only the lifespan of human beings but of the Earth itself. Death looms over all life, a fact that manifests itself in these poems as a call to action. In Castillo’s poetic landscape, the storm is not on the horizon, we are standing in its eye, taking on wind and water.

Since the book’s official Sept. 1 launch, reviewers almost universally praised the work both for its artistry and its powerful messages.

Caitlin Archer-Helke, writing for Third Coast Review, said, “Castillo was born and raised in Chicago, and the city’s neighborhoods and people move across the pages of My Book of the Dead, sometimes with beauty, sometimes carrying rage colored by grief. It’s impossible to read several of the poems here, particularly the heartbreaking ‘Homage to Akilah,’ without thinking of Laquan McDonald or Adam Toledo, or of the ways in which disinvestment and inequity have been baked into Chicago’s funding models and policing strategies for generations.”

Dontaná McPherson-Joseph, in a review for Foreword Reviews, wrote, “With a sharp eye and even sharper wordplay, the poems radiate with emotion, from anger to heartbreak. Beginning with ‘A Storm Upon Us,’ a memorial poem for a friend, and continuing through ‘Drops Fell on the Roof,’ honoring the lost students and staff of the Parkland shooting, the spectre of death hovers over the collection.”

Jael Montellano, in an introductory passage to her Hypertext interview with the author, wrote, “There is something about Ana Castillo’s latest poetry collection, My Book of the Dead, that has the quality of being woven. I imagine this mythic feat as elemental, threads stretched over the heddles and beams of a loom as the artist methodically works tender fingers to entwine this complex masterwork like wall tapestries of old, luxurious in detail but just as impressive in span and width, in chronicling pasts that might be lost to the excess of the endless news cycle, colonialism, capitalism, and more.”

Castillo traveled to Chicago as part of the book’s promotional tour last fall, appearing at Dominican University in River Forest last Sept. 15 and Women & Children First in Andersonville two days later. She will be back in town on March 24 to receive the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement, in a ceremony at the American Writers Museum.

We exchanged questions and answers via email and also talked on the phone, me in Oak Park and she in southern New Mexico, a rural area between Las Cruces and El Paso that has been her permanent home since 2008 and before that her retreat. This is where for nearly a decade Castillo has hunkered down to her serious writing.

Cruces and El Paso that has been her permanent home since 2008 and before that her retreat. This is where for nearly a decade Castillo has hunkered down to her serious writing.

DGE: My Book of the Dead is both a beginning and end, the title of the collection but also the final poem.

You write,

“When the best, which is to say the worst

rose from the swamp,

elected to lead the nation—

I presumed my death was imminent.”

There is urgency in these 48 poems, sometimes offset with resign. The title poem has an almost Biblical feel. It’s not just politics, though that, too, but a condemnation of humanity, a shout that we must do better not just for ourselves but for the greater good. Tell me about this poem. Why did you draw the collection’s title from this, rather than, say, one of the other 47 poems?

AC: Historically, I believe, the poet has often been viewed (in retrospect) among the first to sound the horn. My Book of the Dead developed in times of a pandemic--riots in the streets, protests against the ongoing killings of black people, and a government in place which from the onset showed signs of Fascism, White supremacist ambitions, and global warming denial despite natural catastrophes becoming near commonplace as the numbers among the dead from these causes rose. As a title, it seemed appropriate and timely.

DGE: Three of your own illustrations are included in the book, fine tip, free form ink drawings, of an elegant, seated younger woman wearing a snake like a boa; a somber, standing, middle-aged, face-masked woman; and a joyous, dancing skeletal woman. The drawings teem with various expressions of life and culture. Tell me about this artwork and your desire to include some of it in this collection.

AC: I began to draw these line drawings around 2015 or 16. Pretty much whatever came to mind, I would draw it. I was teaching the summer program with Bread Loaf up in Santa Fe. I spent a lot of time alone. I am not a big TV watcher, I don’t go out and socialize a lot. I started doing them as a way to occupy myself. With the elections of 2016, I fell into this deep clinical depression; I actually believed I would just give up writing altogether. These drawings kept me afloat while I was very actively getting myself out of that depression. It was like a life raft. The female drawings are expressions of my spirit, to some extent self-portraits, and they also tell what I might have written if I was writing. I’m very modest about the drawings and reserved about them. They’re free hand. I left my ambitions to be an artist years ago, but I just felt like this kind of expresses a lot of these poems, what they represent.

DGE: The dead populate your poetic landscape, whether it be in dedications or fictional scenes or as spirits whose influence remains. How do you think about death, and in what ways were you able to explore your worldview through poetry?

AC: I imagine death with a question mark.

Years ago, I had a near-death experience which I wrote about. It’s in my essay collection, Black Dove. I’m grateful for it because I accept my mortality without apprehension.

My lifelong quest trying to understand something of the theology of the indigenous peoples in the Americas leads me to sources that provide their ideas and answers to questions about the meaning of life and the afterlife. These references appear in some of the new poems, especially “My Book of the Dead.”

Informally, I’ve researched other ancient world cultures, in particular with relation to the Cosmic Mother. It’s no secret that I am dedicated to Our Lady of Guadalupe. I’ve made fiction references to the subject and written about it in non-fiction books, the anniversary edition of Massacre of the Dreamers and The Goddess of the Americas anthology. I also put out a coming-of-age, illustrated book some time ago about my ancestor teachers, My Daughter, My Son,The Eagle, the Dove.

DGE: Why is poetry the right medium for this?

AC: Azade Seyhan, a Turkish scholar and critic who generously provided advanced praise for the book, may have put it succinctly when she wrote that I offer “the consolations of poetry in the face of current crises…”

That is the reply to the final product manifested in the midst of crises on so many fronts, a book of poems.

For me, a collection may take as long as a decade to complete. I made the decision in 2012 to work on new poetry. Over the following years, poems were added and others deleted. The opening poem, “A Storm Upon Us,” was written in 2015. Yes, poems with such ‘urgency’ may serve as the sound of the bugle, call to prayer from the minaret, sirens answering a nine-alarm fire, the deafening noise of an air raid siren—everyone get under your desks! Run for cover! Jump deck! In between, it may be quiet. We reflect on our lives and, yes, our mortality.

Poetry, at its best, may capture a moment but oh, what an image! Tic, tic, tic, the rain falls on the flat roof of an adobe on the Valentine’s night when seventeen youth have been massacred with no good explanation but that we allow military weapons in the hands of civilian predators. Click, click, scenes of a marriage between two aging individuals seeking companionship when most of living and life is behind them. A spider that methodically eats its prey alive is a metaphor for each of us systematically being consumed while we ourselves are wasteful consumers. But is it only a metaphor?

Moments as rosary beads, nothing else exists but the present, says a Buddhist monk. Poems invite you to look directly into the moment. Once in it, you’re not allowed to escape. You cannot un-see what you’ve seen except by willful ignorance.

DGE: Your long, successful career needs no embellishment. At this time in your life, how do you choose your projects? Why this? Why now?

AC: You asked above why poetry now and I have another answer for you in this respect, a personal one. I don’t mind admitting to the deep angst that led to clinical depression after the 2016 election. As a young woman in Chicago, at seventeen in high school, I was actively writing and protesting along with an entire generation throughout the city and world. Pushing toward a half century later, I took to heart the backlash to having had an African American president. Into 2017, I didn’t believe there was any purpose in my writing any longer. Corporate Fascism, fundamentally tied to the legacy of White European supremacy had won—or at least would eventually, I felt.

At the end of 2018, I made a resolution to complete the poems. Baby-steps, as people like to say. As a writer and public thinker, I wasn’t done, not by far. Over the next two years, I worked on the book, edited, translated and organized the manuscript.

Normally, I don’t like the word, “consolations,” because of how it is used in contemporary times. It falls hard on the ear. It sounds like Honorable Mention or a pat on the shoulder. But I understand how Professor Seyhan, meant its use. We derive of histories where consolation gave reprieve. We, who are surviving and trying to thrive, we, who have children to raise in this ambience, we, who are losing our parents or spouses, we, who have sons who’ll be called to wars or be brought down on the streets through drugs, gun violence or police brutality needa soothing voice. The use of “need” penetrated our lexicon one day about twenty-five years ago. Its misuse makes us messy about the difference between wants and needs. Comfort, in times of constant grave loss and ongoing mourning and fears, is a need.

DGE: This collection feels like a call to action—a shout to humanity to do better, before it’s too late. But it’s also highly personal. I’m thinking about “Cancer Poem” that surely arises from your own health battles. How, artistically, do you employ biography in this collection?

AC: I’ve not written about breast cancer except for one poem. However, breast cancer in this country is at near epidemic proportions. It kills. Contracting cancer in one form or another and new forms appearing yearly is due in large part to our abuse of the planet, what we consume and perhaps, even the air we breathe. The poet doesn’t live like a hermit in a cave but is fully integrated in society. We make decisions on where we live, what to eat, how to spend our money and the why is sometimes in the poem. It isn’t always an answer but a question.

DGE: Stylistically, there is no continuity in this collection. The poems draw upon various literary as well as oral story-telling traditions. Yet, all of the poems seem connected, or loosely bound to each other in service of a greater master. Can you speak a little about your technique? Was there a grand scheme that dictated your choices?

AC: My writing style and finding the famous “voice” a writer must discover for herself shifts from piece to piece, subject to subject. While getting a message out—a message from a member of society typically not heard and that is the very reason it must be written, documented—the creative in me must be challenged. Sometimes, the outcome may not be what I wanted or expected but at least, I wasn’t bored, playing it safe or redundant in the process.

DGE: One of the most beautiful lines in this collection, one that stayed with me among a myriad of great lines, is,

“I will have remained

the woman

who stayed behind to clean up.”

The line is melancholy, perhaps even a bit depressing, but also proud. Tell me about this line and how it resonates with other themes in the collection.

AC: Thank you. The poem was written in honor of the occasion of the inauguration ceremony of the current president of Northeastern Illinois University, my alma mater. By this, I’m not saying that I assumed she had a mess to clean up there. Again, it was in these times and I believe, many women of color like her, like myself will be the ones who’ll move our communities forward, picking up from the mess, if not the ravages or picking through the rubble of what is being left of Western Civilization, i.e. White patriarchy, today, corporatism.

Another item in the collection, about the disgraceful burning of the Amazon by orders of its current leadership, is a persona poem. It is told in the voice of an actual woman, an indigenous chief. She is learning Portuguese and to read and write to get the word out about the systematic extermination of her people and the Amazon—which is devastating to the planet.

DGE: Chicago makes brief appearances in this collection, but perhaps hovers over select poems in significant ways. “These Times” features such memories, in the lines, “tes de mi abuela/from herbs grown in coffee cans on a Chicago back porch,/tears of my mother on an assembly line in Lincolnwood, Illinois”

It seems to me that because of the nature of this book, which looks forward and backward, often from the perspective of an older woman, Chicago necessarily factored into its construction. What about Chicago helped you write these poems, make them better?

AC: My paternal grandmother arrived in Chicago with her family around the time of the Mexican Revolution, around 1910. My father was born in Chicago, as was I, my son and now my granddaughter. Everything about growing up, being educated and street schooled about Chicago has contributed to my writing. My Chicago friends over life will smile when I say, Chicago made me tough. But I’ll add, having lived in California and briefly in the Bronx, I’m glad it also gave me heart and humility. Does that make the poems better? You tell me.

DGE: The material world manifests itself as a kind of villain, or at least a red herring. “Everybody Wanted Everything” ends with the line, “No one would take her/from her.” You write poignantly and convincingly about how the desire to possess craters our ability to thrive on a more ethereal level. Did you consciously want to explore thoughts about materialism or is it more just baked into your sensibilities as a woman and artist?

AC: In that particular poem (which, like many in the collection, I don’t recall the exact impetus for writing) I’d say the latter. However, I do believe, as you’ve said here earlier, I’m addressing the gross consumerism of all, exploitation of natural resources and the greed of the one percent.

DGE: Finally, as you embark on the publicity stage of this project—the writing now fairly well behind you—what about this book inspires you to find readers?

AC: I was pleased and honored to hear that the press would put the book out as soon as it did while this country and the world are still in crises I address. Again, we go back to the quote about the “consolations of poetry.” Honestly, there are so many “poets” in this country, in the world now, one does feel an urgency to scramble to ‘find’ readers,’ mostly through social media. Because of the pandemic the stage is now virtual. Some kind reader might say my poems are medicine. We’ll see if the book can wade through the mire of so many publications in the midst of so much distress and uncertainty in the world.

DGE: Thanks for taking the time to do this, Ana. I very much enjoyed this collection. I’m just a bit younger than you, but I found myself, like the narrators, reflecting on the past and taking inventory of the present and wondering what comes next. Congratulations on this; it’s a real accomplishment.

AC: It’s been an honor, thank you.

Donald G. Evans is the author of three books, most recently the story collection An Off-White Christmas, and Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. He is the co-editor, along with Robin Metz, of a Chicago poetry anthology that will be released on June 13 of this year.