An Interview with Marianne Boruch

Wednesday, September 7, 2022

Chicago is a city tied with identity, its eight million residents hailing from all different backgrounds, cultures, and countries. Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry is the cross-section of that city-wide identity, exposing slices of life from a variety of angles.

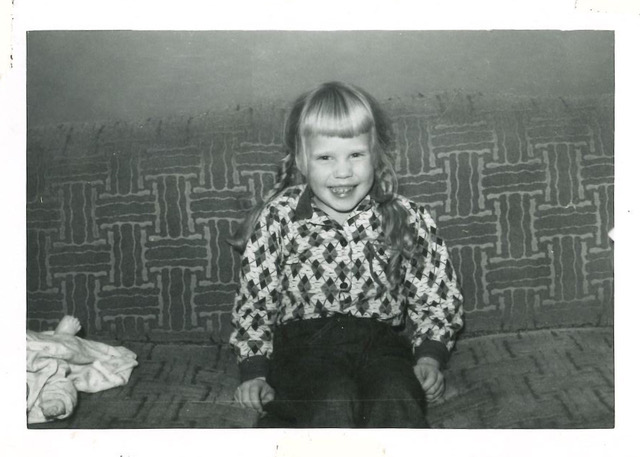

I reached out to Marianne Boruch, who contributed her poem Once at Berghoff’s (115) to the anthology. Boruch was born and raised in Chicago, the child of Catholic parents. While she spent most of her early life in Illinois, she currently serves as Professor Emeritus of the MFA program in creative writing at Purdue University.

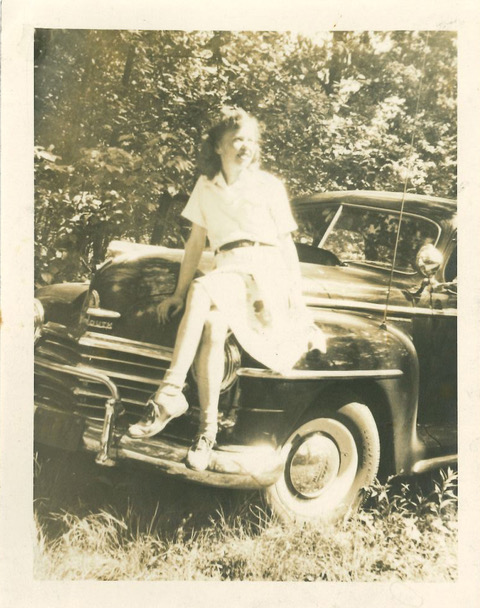

Boruch has written numerous collections of poetry, the most recent of which include The Anti-Grief (2019), Cadaver, Speak (2014), and The Book of Hours (2011), which won the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. Throughout her career, she has acquired honors such as fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, residencies at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center, and has served a Fulbright/Visiting Professorship at the University of Edinburgh. Her writing runs the gamut from childhood memories, to explications of age and mortality, to the recounting of a particularly memorable hitchhiking trip. All of it, however, is marked by a distinct authenticity and a powerful sense of identity. As David Young observes, “[her poems] build toward blazing insights with the utmost honesty and care.”

What city is better, then, to parallel Boruch’s undaunting perception of self, than Chicago? In our conversation, Boruch gave me insight into the process of writing her poems, the identity she feels is intertwined with her poetry, and how her poetry fits into the broader identity of Chicago as a whole.

BC: What was the inspiration for this poem? What made you decide to write on this subject?

MB: Well, childhood is always a rich source of imagery and strangeness for any poet, and this was a memory I couldn’t shake. Having lunch in a fancy restaurant is something my family never did really … but for some reason my mother got it into her head that she and I should dress up and have lunch in the Loop and she knew and apparently loved Berghoff’s … I was 12 or so. I remember it was fall—time of beauty and grief and dismemberment. Piles of burning leaves in the neighborhoods. All this flooded into me and the poem just churned it around. It suddenly got so mysterious—my bratty reluctance, my mother’s surprising wish for elegance, the iconic leaves burning into ash mid-century, the rhythmic raking that makes that season feel ancient—I could hear it again too.

MB: Well, childhood is always a rich source of imagery and strangeness for any poet, and this was a memory I couldn’t shake. Having lunch in a fancy restaurant is something my family never did really … but for some reason my mother got it into her head that she and I should dress up and have lunch in the Loop and she knew and apparently loved Berghoff’s … I was 12 or so. I remember it was fall—time of beauty and grief and dismemberment. Piles of burning leaves in the neighborhoods. All this flooded into me and the poem just churned it around. It suddenly got so mysterious—my bratty reluctance, my mother’s surprising wish for elegance, the iconic leaves burning into ash mid-century, the rhythmic raking that makes that season feel ancient—I could hear it again too.

BC: What was the process in writing this poem? Was it different or similar to your usual one?

MB: My habit has long been what I call my “begging bowl” method. I go blank and put out the bowl and images drop in and I go from there. I don’t have an agenda, really. One thing leads to another if I am quiet and attentive enough. And I revise like hell—a practice I call my “hospital rounds.”

BC: Your poem is a very unique experience in Chicago. Do you feel writing about Chicago is different from other subjects in poetry?

MB: The fact is Chicago is big and I am little. One is surrounded, flooded, really, with other lives and worlds. It was never just a poem about me, God forbid. The place has always been a source of wonder though I left for good in 1976 when I was 26. It haunts me.

BC: What does identity mean to you? Are there aspects of your identity you feel are important?

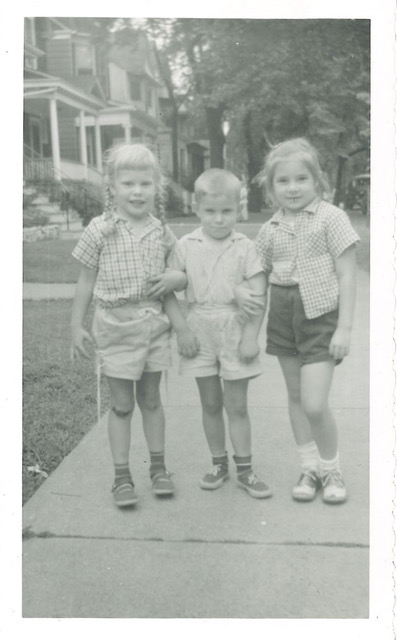

MB: People laugh when I say that the only “group” with which I fully identify is “lapsed Catholic”—but it’s true. Other than that, I guess I’m your standard middle-class American mutt, meaning I’m a crazy mix of DNA. I recall from childhood that when someone moved into the neighborhood, we kids got curious, asking first “what are you?” And whoever it was would rattle off a list of nationalities. We just took it in with a shrug though the more countries you could name, the cooler it was.

We were that close to a universal notion of immigration. My son’s generation didn’t do that and I can’t decide if that’s a good thing or not. But it seemed like a lot of kids in the 50s and 60s had a non-English-speaking grandmother in a babushka in a back room lamenting something. Which made us aware of the great world out there, and difficult life passages.

BC: Are there aspects of your identity you feel have an important impact on your poetry?

MB: Yes, of course—on my poems and my life. The marginal aspects in one’s sense of self are the most vital for a writer, and to be cherished. Growing up Catholic, for one, and going to parish schools was definitely a marginal experience in the last century at least, in a mostly Protestant culture. Being female is, by definition, always marginal. Being from the Midwest, for sure—the “cross-over” part of the country that both east and west coasters stare down at from airplane windows and shudder—or simply sleep through! No matter where we Midwesterners end up living, that sticks with us. But whatever out-of-the-main feel, that’s crucial for a writer, I think. We’re outsiders, loners, and mostly glad to go solo. A poem is, after all, the work of an individual, a totally DIY literary form. And thank Zeus for that!

BC: How does your identity intersect with Chicago? Do you feel you have a unique place in the city?

MB: I don’t really—have “a unique place,” I mean. I think of poet Paul Carroll coining the term “big table,” by which he meant the way poetry should be and putting that into action by way of his lovely The Young American Poets, published in 1968, an anthology I still dearly love. Paul was one of the great Chicagoans who generously, like Bill Knott, let me sit in on his workshop for free in the early 70s. Whatever they passed on, was that Chicago-esque? I don’t know, but I am still grateful.

BC: Do you feel your identity is impacted by having lived in Chicago? Would it be different if you had lived in any other city?

MB: Surely I’d be a different person growing up in London, New Orleans, Melbourne, Delhi, Johannesburg, Seattle … or anywhere else. But I suppose Chicago, which always has felt both new and old to me, both step-by-step/street-by-street and vast, has nicely messed with my ability to define anything accurately and therefore go for odd instead.

BC: How does your poem fit among the others in Wherever I’m At?

MB: Maybe it doesn’t fit at all. As a boomer, I’m no doubt one of the oldest poets in the book; certainly the poem the editors kindly included was one of the earliest I wrote … As for why I am in the anthology at all--I was asked long ago by the late and beloved Robin Metz to send in some work for the anthology, and I was happy to do that, though I fear I’m a bit of an imposter, given that most of my adult life has been spent elsewhere and continues to be. But just now it occurs to me that perhaps that could be a key meaning of the book’s title: Wherever I’m At! So I guess it doesn’t matter that I’ve taught and lived in Indiana for 30+ years. As Flannery O’Connor wrote (paraphrasing here): if you’ve managed to live through your childhood, you have enough material for a lifetime.

BC: Is there anything in particular you want readers to take away from your poetry?

BC: Is there anything in particular you want readers to take away from your poetry?

MB: Emily Dickinson famously wrote in a letter to Thomas Higginson, editor of The Atlantic, that she wanted her poems “to breathe.” I’ve always felt that made sense though I’m not sure what that means exactly. Poems as C-Pap machines? The kind that go all night, companions to the deepest dreaming, in and out of many worlds? Maybe that’s my aim, that kind of discovery sleep brings, ancient and only half-human.

BC: Is there anything else you would like readers to know?

MB: I do think poetry, our oldest way to access the interior, is the closest literary form we have to silence. But that doesn’t seem to stop our talking about it so much! Weird, isn’t it? That poets love to talk about poetry: what it is or was or will be. Our curious obsession and reverence for the form feels somehow inevitable. I never hear fiction writers hold forth about fiction this way. Go figure … we’re crazy.

Brian Clancy is a senior in English at DePaul University. He just completed a summer internship with the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.