A Lucky Gold Miner: Alex Kotlowitz Stakes His Claim

Tuesday, September 17, 2024

by Miles Harvey

What Alex Kotlowitz remembers about his first apartment in Chicago is lugging dozens of cinderblocks up three flights of stairs to build makeshift bookshelves for his growing library. He remembers the downstairs neighbor who ran an informal bike-repair shop out of his first-floor flat and the heroin addicts across the way who ended up breaking into the young writer’s apartment through the transom above his door, stealing his record albums. Those burglars might have been hoping for better loot, he jokes, but “I didn’t have any actual valuables.”

He remembers the excitement surrounding Chicago’s first black mayor, Harold Washington, who’d been elected a few months before Kotlowitz arrived in town in late 1983. He remembers the ragged beauty of Wicker Park in those pre- gentrification days, a “really diverse neighborhood,” where he spent hour after hour on an outdoor basketball court with other playground athletes of various races and ethnicities. He remembers his apartment’s ancient free-standing gas heating unit–the lone source of warmth in the whole place. “That first winter was really, really cold,” he recalls. “There was ice on the inside of my windows, and I had to move my mattress into the kitchen to sleep on the floor next to the space heater.”

Kotlowitz also remembers the building on the other side of Evergreen Avenue–a three-story, red-brick walk-up that sometimes attracted fans of a famous local figure who had resided there from 1958 to 1975. By coincidence, the young journalist found himself living right across the street from a former residence of one of Chicago’s most renowned authors, Nelson Algren.

Now, more than 40 years later, Alex Kotlowitz is himself being honored as one of the city’s most important and influential writers, the 2024 recipient of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s Fuller Award for lifetime achievement. But looking back on those early days in his adopted metropolis, the transplanted Manhattanite admits he was so unfamiliar with the local literary scene that “I didn’t even know who Algren was.”

He has since come to respect his iconic predecessor as “a guy who lived in this kind of dark undercurrent of the city and just captured it so beautifully.” Kotlowitz particularly admires Algren’s book-length essay Chicago: City on the Make but admits to finding the older writer’s fiction “kind of an acquired taste.” Nor, Kotlowitz concedes, has he managed to read The Cliff-Dwellers or any other novels of Henry Blake Fuller, the writer after whom the award he is receiving tonight is named. But while those two members of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame didn’t make much of an impact, another inductee played a pivotal role in Alex Kotlowitz’s career.

***

Kotlowitz met the Pulitzer Prize-winning oral historian Studs Terkel shortly after arriving in town. The 28-year-old newcomer had grown up in New York City, where his mother, Billie Kotlowitz, was a teacher and program director at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and his father, Robert Kotlowitz, was a public television executive who, among many other varied accomplishments, helped bring Monty Python’s Flying Circus to American audiences. The prolific Robert Kotlowitz also managed to write four novels, which was what gave his son an excuse to meet Terkel. “My dad had done an interview with Studs, and I never heard it because it was on WFMT,” Kotlowitz recalls, referring to the Chicago radio station that was home to Terkel’s long-running program. “And so I went down to FMT to listen to that interview.”

But while interested in the interview itself, Kotlowitz was perhaps even more excited to meet the man who had conducted it. During his undergraduate days at Wesleyan University, he’d read Terkel’s Working, a monumental oral-history in which more than 100 Americans describe the daily routine of their jobs and, in so doing, reveal their passions, hopes and anxieties. “I was just like, ‘Wow, this is poetry–the poetry of everyday people.’ I was just blown away by that book. And then I read Division Street: America, which is still so resonant it just feels like it could have been written today,” Kotlowitz says. “And so, one of the things I’ve done over the course of my life, if I find writers that I really admire, I make a point of trying to meet them.”

Although separated in age by more than 40 years, the two writers soon became good friends, with the older one taking on the informal role of a gravel- voiced, cigar-smoking mentor. “He had an enormous impact on me,” Kotlowitz says. “There are two things I learned from him. Everybody says, ‘We learned how to listen from Studs.’ But the truth is that he never shut up. He loved to talk. And I remember when I first met him I thought, ‘How is it that this is the guy who has gotten everybody to open up? Because how do they get a word in?’ But I came to realize that listening is a kind of active exercise. He just engaged with people. He laughed with them, cried with them, argued with them. And the other thing is, he was such a generous person. You’d go into his house, and he’d have all these manuscripts from other writers piled high. He read everything that came through that door. And whenever I get asked for a blurb, I always think of Studs because he didn’t turn anybody away.”

voiced, cigar-smoking mentor. “He had an enormous impact on me,” Kotlowitz says. “There are two things I learned from him. Everybody says, ‘We learned how to listen from Studs.’ But the truth is that he never shut up. He loved to talk. And I remember when I first met him I thought, ‘How is it that this is the guy who has gotten everybody to open up? Because how do they get a word in?’ But I came to realize that listening is a kind of active exercise. He just engaged with people. He laughed with them, cried with them, argued with them. And the other thing is, he was such a generous person. You’d go into his house, and he’d have all these manuscripts from other writers piled high. He read everything that came through that door. And whenever I get asked for a blurb, I always think of Studs because he didn’t turn anybody away.”

But Terkel also seems to have had a more subtle, perhaps unspoken influence– helping the younger writer to see that Chicago was a place where he could seek a new direction, a place where he could feel at home. “I found New York really competitive,” Kotlowitz says. “Growing up there, you’re kind of looking over your shoulder at everybody else, thinking, ‘I should be doing that, doing this.’ Everybody was so beautiful and stylish. They just seemed beyond reach. And it didn’t feel that way here. I just felt like Chicago was a place where I could fail and I’d be okay. I looked at somebody like Studs, who had just carved out this amazing life for himself here. And I don’t think he could have done that somewhere else. I mean, what’s remarkable about Studs is he was in his mid-50s when he wrote his first oral history. So he kind of reinvented himself.”

* * *

Kotlowitz’s own path to becoming an author was full of false starts. Like Terkel, he was always interested in writing about people on the margins, people locked out of political and economic power, people whose lives go mostly unnoticed by the mainstream media and the world at large. “I knew I wanted to tell stories about people who Studs called ‘the et ceteras of the world,’ people who had been shunted aside and misunderstood,” he recalls of those early days. “But I didn’t know what shape or form my career would take.”

Indeed, he came to Chicago without a solid job offer, having recently left a gig at an alternative newspaper in Michigan under less than happy circumstances. “But I was welcomed in by Chicago journalists and immediately found a community here,” he says. First, he found steady freelance work at National Public Radio’s Chicago bureau. Then, in 1984, he was hired as a staff writer for The Wall Street Journal’s Chicago bureau, a job he held for most of the next decade.

That book would have been set in Rockford, Illinois. “André wanted me to write about a Midwestern industrial town,” Kotlowitz explains. “I wanted to do Flint, Michigan, but I knew that wasn’t possible because I was here in Chicago. So I was going to do Rockford. It was a really good idea for a book, but I had just been hired at the paper. There was just no way I could pull it off. And so, after coming down from my coffee high and returning to Chicago, I realized, ‘What the hell was I thinking?’ And I had to call him up and just say, ‘André, I can’t do this.’”

A few years later, Kotlowitz nearly missed out on yet another chance to write a book. That opportunity arose from a front-page story he wrote for The Journal in 1987, documenting three months in the life of fifth-grader Lafeyette Walton who endured almost daily violence at the Henry Horner Homes public housing project on the West Side. “That story got more attention than anything I’ve ever written before or since for a newspaper or magazine,” he recalls.

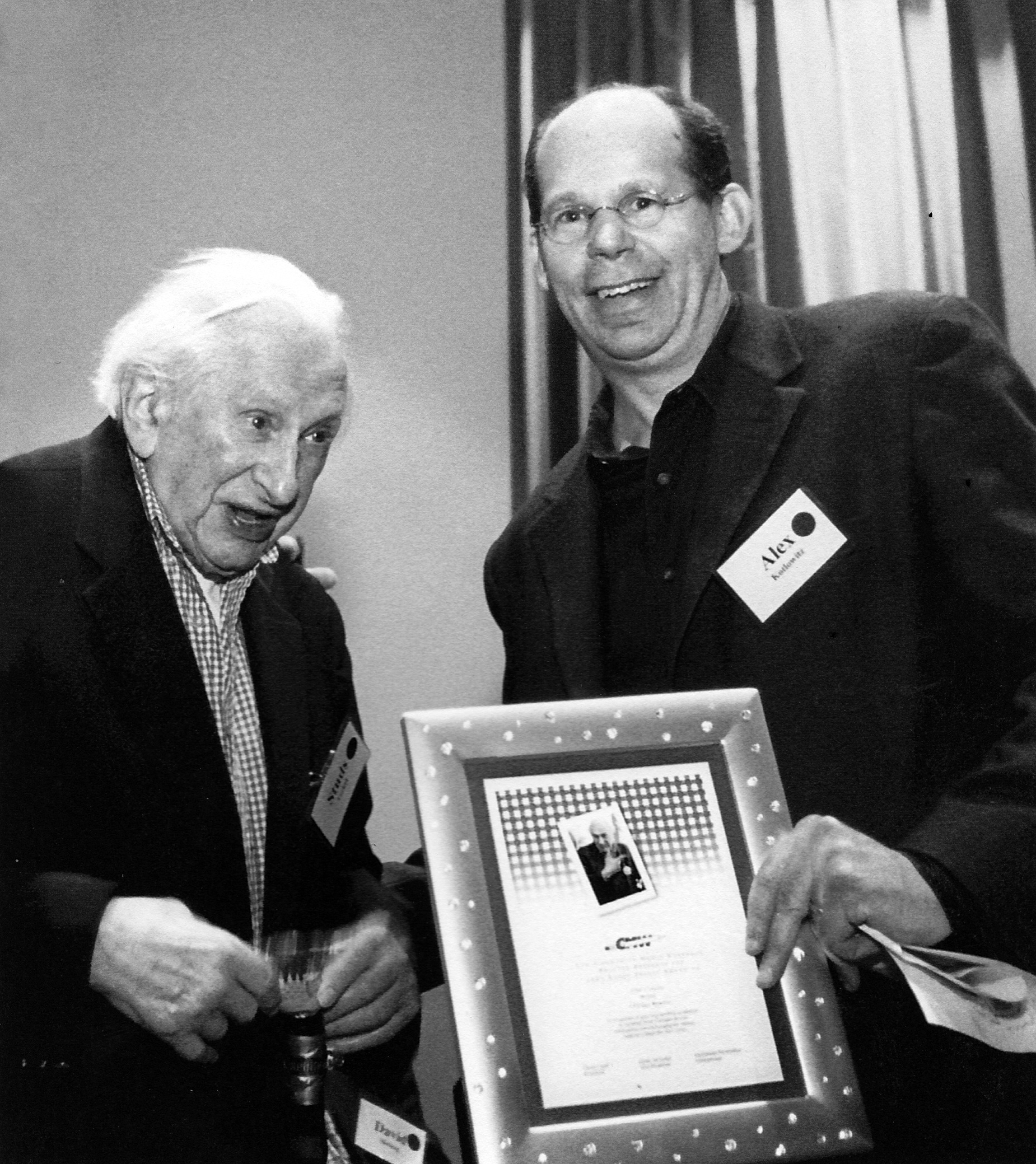

Kotlowitz was inundated with calls from editors about the possibility of a book. But he turned all of them down. “I just felt I’d said everything I wanted to say,” he explains. “And fortunately, a few months later, I got a call from David Black, who’s been my agent now for 40 years–just a real mensch. And he kind of talked me through things and convinced me there was a book there.”

The acclaimed author is well aware that were it not for that pivotal conversation, his career might have taken a very different path—one that would probably not have included There Are No Children Here, the career-changing masterpiece that the New York Public Library selected as one of the 150 most important books of the twentieth century. “There was a lot of luck involved,” he says with a contemplative smile. “It’s not dumb luck. It’s not like you just stumble into something. I think I have a really good eye for story, and I had to work really hard at becoming a good storyteller and a good reporter and good interviewer. But it’s kind of like you’re mining for gold and you have the tools and you know what you’re looking for and you know where to look–but nonetheless if you find it, you feel like you’re pretty goddamn lucky.”

***

When he contemplates his remarkable career, the 69-year-old Kotlowitz says, “I’m really hard on myself, but in the end, I don’t have any regrets about the path I’ve taken. Perhaps I have regrets about stories I didn’t pursue or moments when I probably wish I’d stood up to an editor. And I wish I’d written more books. You know, the idea when I left The Wall Street Journal back in 1993 was that I was just going to work my way from one book to another, and I quickly learned I could not do that. It was just too hard. So I found another way to pull together a writing life”--one that included numerous audio pieces for This American Life and articles for The New York Times Magazine and The New Yorker, as well as years of teaching at Northwestern University.

“Looking back at my 28-year-old self, I’d say, ‘You should feel better about yourself. You lack confidence,’” he adds. Even today, Kotlowitz claims to be in “a constant state of self-doubt. It’s what provides all my angst, and I also think it’s what drives me. And it’s why you have other friends who are writers, because hopefully you don’t all have self-doubts at the same time, and you can lift someone else up while you’re riding reasonably high and vice versa.”

He is quick to express gratitude to fellow members of the Chicago literary community, whom he finds remarkably supportive as a whole, as well as to several superb collaborators, including Nan Talese, the legendary book editor, and Julie Snyder, the pioneering producer for This American Life and the Serial podcast series. He’s also incredibly grateful for the friendships he’s made with many of the people he’s written about, who he says, “have given my life such richness and fullness.” But he saves his most effusive thanks for his wife of 31 years, the attorney and advocate for immigrant children’s rights, Maria Woltjen. “I’m the luckiest man in the world to have met and fallen in love with her, and to have her fall in love with me, which is more remarkable,” Koltowitz says. “Maria is my best friend. She’s also my first reader, and she is as straight and as blunt as they come, which I really appreciate. I don’t send anything off, even to my editor, without having Maria give it a read.”

Serial podcast series. He’s also incredibly grateful for the friendships he’s made with many of the people he’s written about, who he says, “have given my life such richness and fullness.” But he saves his most effusive thanks for his wife of 31 years, the attorney and advocate for immigrant children’s rights, Maria Woltjen. “I’m the luckiest man in the world to have met and fallen in love with her, and to have her fall in love with me, which is more remarkable,” Koltowitz says. “Maria is my best friend. She’s also my first reader, and she is as straight and as blunt as they come, which I really appreciate. I don’t send anything off, even to my editor, without having Maria give it a read.”

He’s in the early stages of a new book project that he’d prefer not to say much about, in part because he still finds long-form storytelling to be such a difficult endeavor. “Oh God, it’s so fucking painful,” he says. “Writing is really hard. And it can be so lonely. For me, it’s about making sense of what you’ve seen and what you’ve heard and what you’ve experienced. And that’s tough. It’s like being in therapy in some ways, except you’re doing it on your own. But there’s also something magical about it. I mean, you wake up one day and think, ‘Holy crap, I did this.’”

And he plans to keep right on doing it. Over the course of his long and extraordinary career, Kotlowitz has crafted nonfiction narrative by means of virtually every medium available to him–books, newspapers, magazines, radio shows, TV programs and podcasts, as well as documentary films, most notably the award-winning 2011 feature The Interrupters. And although he has no idea what the media landscape will look like in the years to come, “I can’t imagine that we don’t have platforms to tell stories,” the 2024 Fuller Award-winner concludes. “Stories are just so much a part of what it is to be human. They bring us places we otherwise wouldn’t go. And they also affirm our own experiences. They make us feel less alone.”

Miles Harvey is a professor at DePaul University of Chicago, where he is chair of the Department of English and director of the DePaul Publishing Institute. He has authored three works of nonfiction, The Island of Lost Maps, Painter in a Savage Land and The King of Confidence as well as a 2024 collection of short stories, The Registry of Forgotten Objects.