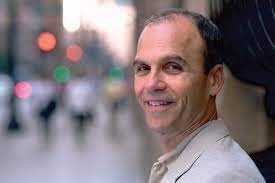

A Conversation with Fuller Award Recipient Scott Turow

Sunday, September 24, 2023

Scott Turow speaks in fully formed, piercing sentences, so much so that if his off-the-cuff remarks were transcribed, they would read like polished prose.

I’ve seen him deliver truly delightful and smart lectures, pitch perfect down to deliberate pauses, with nary a notecard in sight. He is a writer and attorney—a sentence that, while true, does a grave injustice to the heights he has ascended in both fields.

Turow was born on April 12, 1949 in Chicago. After graduation with high honors from Amherst College in 1970, he received an Edith Mirrielees Fellowship and attended the Stanford University Creative Writing Center. He taught Creative Writing at Stanford as E.H. Jones Lecturer from 1972-75. He then enrolled at Harvard Law School, graduating with honors, and from 1978 until 1986 he worked as Assistant United States Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois. Starting in 1986, as a partner in the Chicago law firm of Dentons LLC, Turow devoted a substantial part of his time to pro bono matters. In the late 90s and early aughts, he served on various commissions and advisory boards addressing such matters as the appointment of federal judges, capital punishment reform, Illinois State Police personnel matters, and the representation of indigent criminal defendants.

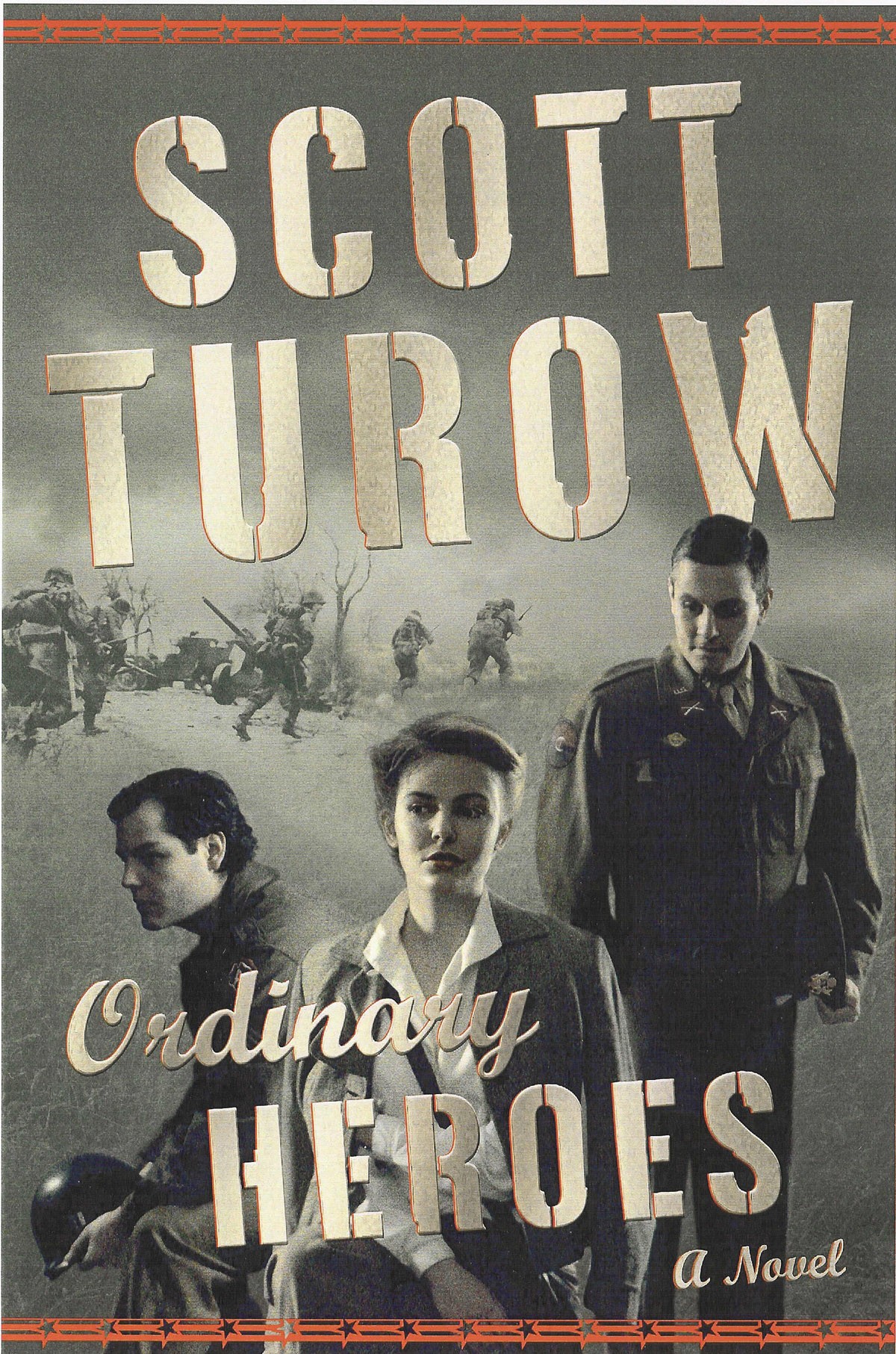

Turow has authored 13 best-selling novels, including his latest, Suspect, which was published in September, 2022. He has also written three non-fiction books. These books have been translated into more than 25 languages and have sold more than 40 million copies worldwide. His essays and opinion pieces appear in all the best periodicals, like The New York Times, Playboy and The Atlantic.

Turow’s extraordinary legal career has served as the underpinnings to so much of his literary work—creatively, intellectually, and practically. Though Turow retired from commercial practice in 2020, the stories he heard and characters he knew remain grist for his literary mill.

He breathes that rarefied air only a handful of authors even whiff: a bestseller and a respected literary figure. He is a celebrity, in as much as writers can be. He counts among his close friends other bestselling authors such as Dave Barry, Stephen King, and Amy Tan. Turow’s novels have been adapted into a number of films, as well as two TV mini-series and a TV movie. Turow seems to neither relish his celebrity, nor downplay it, just accepts it for what it is. Fame and fortune might have factored into Turow’s ambition to be a writer, but that desire never seemed to dominate his process. All along, Turow has said that nothing matters in the end but the work itself. He ascribes his success, at least in part, to luck—he seems to really believe that his status as a worldwide literary phenomenon, given a different set of circumstances, might have gone to somebody else, or at least not to him. He cites as proof the fact that it took him five tries to even get his first novel published.

But the evidence in favor of luck also provides evidence of determination. Turow’s work ethic is off the charts. In the beginning, he wrote beautifully and prodigiously in the precious off-the-clock moments his legal career allowed. Even as he recalibrated the balance between literary and legal pursuits, he was raising a family, trying important cases, maintaining the aggressive touring schedule demanded of a popular author, answering calls for involvement in various cultural and political causes, throwing off brilliant essays even as he toiled away at the next big book, helping guide younger authors, and so on.

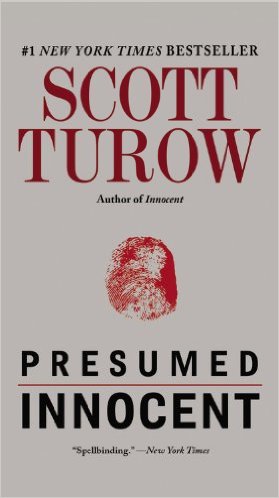

Even after Turow hit it big with his first novel, Presumed Innocent, he refrained from the publishing industry’s siren call to write more books at a faster clip. Turow needed time to explore the human condition and psyche that makes his stories so much greater than their compelling plots. He strives, always, to create the best book of which he’s capable. It’s never been worth it for him to sacrifice the pride that comes with that.

Even after Turow hit it big with his first novel, Presumed Innocent, he refrained from the publishing industry’s siren call to write more books at a faster clip. Turow needed time to explore the human condition and psyche that makes his stories so much greater than their compelling plots. He strives, always, to create the best book of which he’s capable. It’s never been worth it for him to sacrifice the pride that comes with that.

The following interview took place over a series of email exchanges in August and September of this year, 2023, just before the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame’s ceremony to honor Turow for his lifetime achievements. The CLHOF’s Fuller Award selection committee, in deliberating its candidates, considered nothing but the work itself.

DGE: Chicago is your birthplace. Where exactly?

ST: My parents were living at Arthur and Leavitt on the North Side when I was born. The actual birth was at Edgewater Hospital, now the Bethany Home, on Ashland.

DGE: Tell me about your family. What kind of environment did you grow up in?

ST: My dad was an OB-GYN on staff at Edgewater, with an office at Devon and Sheridan. My mom was a would-be writer. I have one sib, my sister, Vicki, whose twin died in childbirth and who is almost three years younger. She is a retired clinical psychologist. Both my sister and I had a difficult relationship with my father. His mother had died when he was about four years old and he really needed my mother to himself. My mom, who had taught at Prescott School before I was born, was a very bright person and a very good reader. She wrote a psychological autobiography of herself while she was doing her Master’s degree at Roosevelt. I read it after she died and wondered what happened to the honest, perceptive 23 year-old who saw much more of herself than I had realized.

DGE: You’ve written about your dad, and used him as a model (at least somewhat) in your fiction. You’ve said in other interviews that he was a spectacular liar. What did you make of him then, and later, as you became your own sort of spectacular liar, in the form of a fiction writer?

ST: It will tell you something about my relationship with my dad that your unintended comparison of the two of us raises my hackles. My dad was what the psychologists would call an incomplete personality, who used many inventions about himself (some of which I discovered in writing about him) to allay his own questions about who he was. But he was often angry and belittling to my mother, and particularly, to my sister and me. I think my own obsession with the misuse of power, which has been both a literary theme and a dominating concern in my law practice, emanated from being Dave Turow’s son. As my mother would have it, he was “a good provider,” and I benefited in countless ways from growing up in an affluent household. To the many people around Chicago who know or knew my dad as a caring physician, these descriptions of him are probably shocking. He was often a far better person outside the house, who did great good for many patients.

DGE: You attended Rogers Elementary School in West Rogers Park. Tell me about your childhood. What kind of kid were you?

ST: Dreamy with little inner discipline. I didn’t like school generally, the whole business of staying in my seat and not talking to friends and having to learn at a prescribed pace. I contrived illnesses to avoid going, which my mom, as a former teacher, tolerated, as long as I was reading something worthwhile at home. I watched a lot of TV, but also read a good deal. But I loved the closeness of West Rogers Park, sometimes called the Gilded Ghetto. I roamed all over the neighborhood with friends. I should also mention that I was obsessed with sports, especially the Cubs and the Bears. Ernie Banks was, of course, my hero. As a younger child, living at Sherwin and Albany in the city, I played a lot of 16” softball, where the pitcher stood on the sewer cap in the middle of the intersection and the curbs of the four corners were the bases. But I was never as good an athlete as I would have loved to be.

prescribed pace. I contrived illnesses to avoid going, which my mom, as a former teacher, tolerated, as long as I was reading something worthwhile at home. I watched a lot of TV, but also read a good deal. But I loved the closeness of West Rogers Park, sometimes called the Gilded Ghetto. I roamed all over the neighborhood with friends. I should also mention that I was obsessed with sports, especially the Cubs and the Bears. Ernie Banks was, of course, my hero. As a younger child, living at Sherwin and Albany in the city, I played a lot of 16” softball, where the pitcher stood on the sewer cap in the middle of the intersection and the curbs of the four corners were the bases. But I was never as good an athlete as I would have loved to be.

DGE: How did those formative years shape your future, and does that time weave its way into your fiction, or even your writing process?

ST: My mother’s own interest in writing clearly had a large impact. She was always at work on something, and was a regular member of writers’ workshops, although she was too often distracted by the shopping and socializing of suburban life. Both my parents wanted me to be a doctor, like my father, and as I think I’ve made clear, I didn’t want to be like him, so I adopted my mother’s ambition as a kind of divide and conquer. I certainly claimed I was going to be a novelist from the time I was 10 or 11 years old, and began my career with a story plagiarized from one of my school texts. (I was relieved recently to listen to an episode of Selected Shorts, where Meg Wolitzer and her mother, Hilma, both confessed to starting out as writers the same way.) I’ve always been a little puzzled by myself, since the ambition to write preceded any sense of what writing actually meant. I can only remember reading The Count of Monte Cristo at the age of 10 or 11, during one of my prolonged school absences and concluding that if that was that exciting to read the book, it must have been even more thrilling to write it.

DGE: When did you moved to Winnetka? Did you attend New Trier all four years?

ST: My parents made me the unhappiest kid in the USA by moving to Winnetka and starting me as a freshman at New Trier. It was a terrible time to move. As I said, I loved the closeness and independence of West Rogers Park. In the suburbs I was isolated. I knew no one and there was no public transportation, so I was pinned down in my parents’ house. I was lost at New Trier until I started working on the high school newspaper as a junior. That became my world. And yes, I graduated from New Trier, vowing never to set foot in the place again, only to send all three of my kids to the school.

DGE: Were you always facile with language? When did you start telling stories?

ST: “Facile with language”—I suppose. I liked talking, as well as writing, and even did a little acting when I was 12 or 13, which led to me being offered a part at Goodman, which I turned down. I made serious efforts at writing short stories by the time I’d graduated high school. The stories were no good, frankly.

DGE: It strikes me as extraordinary for a young, artistic-minded person to turn down the Goodman, and all the thrills and potential acclaim that entails. Your resume documents, all along the way, success at the highest levels. Were you already, at that tender age, confident enough to be so discerning?

ST: I was 13 years old, so I really had no sense of the importance of the offer. But what struck me at that point was that I really wasn’t “a theater person.” I liked acting but I didn’t think of myself as the same kind of emphatic personality as many of the other young people I was exposed to. I realized I was closing a door, but I had few regrets about it then, or in later years.

DGE: From New Trier High School, you went to Amherst College (1970), then Stanford University (1970-72), and finally Harvard University (1978). Were you always on a dual path to become a lawyer and a writer, or did those paths converge at some point?

ST: I arrived at Amherst determined to become a novelist, an ambition which was immediately thwarted when I discovered that no creative writing courses were taught there. Instead, I tried to learn by doing and wrote my first novel over the following summer. I called it Dithyramb, which probably gives you a good idea of what was wrong with it. When I was a sophomore Amherst hired its first writer-in-residence, the English poet, Tony Connor, a very fine writer and human being. Tony told me he knew nothing about how to write a novel, but said if he wanted to be a novelist, he would stuff himself with novels. And that became my plan of attack. I read everything that anyone I respected thought was any good, and became well acquainted with the work of all the major early and mid-century novelists. In the process, I became virtually obsessed with the work of Saul Bellow, a fellow Jewish Chicagoan, often referred to in those days as the greatest living American novelist. I did not fully understand my thrall with Bellow until after he died. Only then did I recall that my father and he had attended Tuley High School at the same time. I suppose I’d hoped that by studying Bellow intensely I could learn more about the world that made my father. I remember my father harrumphing around the house about “Solomon Bellows,” as the author had been called when he was in high school, which my father apparently took as proof that Bellow was some kind of impostor. It tells you something about my dad that I also learned after he died that he had graduated high school known as “David Turowetsky.”

When I was a junior and senior, Amherst’s writer in residence was Tillie Olsen, the exalted fictionist, who became my mentor and inspiration. As a senior, I was freed from taking classes and just read and wrote fiction under the guidance of Tillie and two other professors, the poet David Sofield, and the fabled Americanist, Leo Marx. Two of the stories I wrote that year were accepted for publication in Transatlantic Review. Creating one of those stories found me rising from a fever bed, inspired by an anecdote shared by a date I’d met in Boston the night before. I typed in a state of transport for 18 hours straight. It was the first time I actually felt what it was like to fuse imagination and words, the first moment when I actually believed I was a writer.

Throughout my time at Amherst, I kept close eye on the red-banded announcements of the Stanford Writing Fellowships, which were posted on the English Department bulletin board annually. Many of the writers I most intensely admired—Robert Stone, Ernest Gaines, Thomas McGuane, Larry McMurtry, Tillie herself—had been Stanford fellows and that became my dream. I was awarded one of the fellowships late in my senior year at Amherst, the Edith Mirrielees Fellowship, which allowed me to both write and pursue a Master’s. I also won a fellowship sponsored by the Book of the Month Club and the College English Association. The award ceremony was a luncheon in Manhattan and I received my check from William Styron. I had never seen a person that drunk actually standing up.

My years at Stanford were both wonderful and trying. I loved the company of the other young writers who surrounded me. Some went on to solid and sometimes glorious careers—Raymond Carver, Richard Price, Alice Hoffman, Chuck Kinder, April Smith, Michael Rogers—others were waylaid over the years, especially by drugs and alcohol. But they were all committed to the same struggle I was. The trying part was my own work. I was attempting to will myself to greatness, which is not a good way to get anything on the page.

My years at Stanford were both wonderful and trying. I loved the company of the other young writers who surrounded me. Some went on to solid and sometimes glorious careers—Raymond Carver, Richard Price, Alice Hoffman, Chuck Kinder, April Smith, Michael Rogers—others were waylaid over the years, especially by drugs and alcohol. But they were all committed to the same struggle I was. The trying part was my own work. I was attempting to will myself to greatness, which is not a good way to get anything on the page.

After my fellowship ended, I was hired as an E.H. Jones Lecturer, another program meant to support young writers by giving them a faculty position teaching undergraduate creative writing classes. My years around the Stanford English Department started me thinking that I didn’t want to be an English professor, which was the path I was on. There were too many battles about things that I didn’t think mattered at all. But I had no idea what I was going to do. I considered trying to get a studio job in Hollywood or going into advertising, but the idea that began to grow on me was shocking: going to law school. The novel I was writing throughout my time at Stanford was about a rent strike and required learning about landlord-tenant law, which to my surprise I found far more interesting than English criticism. Until then, I had no idea what lawyers did, but most of my college roommates had gone to law school. By then they’d found jobs. Their work and that of the non-writer friends I made in the Bay Area, who, by no real coincidence, also often turned out to be attorneys, called to me more deeply than anything I recognized as salaried labor, in contrast to writing which I’ve always experienced as entirely personal and part play. Ultimately, I turned down a tenure track appointment elsewhere to go to law school.

One problem was breaking this news to my then literary agent, who’d been trying unsuccessfully to sell the rent-strike novel. I didn’t want to get on the phone with her, and so I wrote her a letter, telling her that it was my hope to be both a lawyer and fiction writer. It sounded so lame and preposterous, that in the middle of the letter, I started spinning out an idea for a nonfiction book about being a law student, since I’d been able to find nothing like that. I didn’t quite say I wanted to write that book, only that it was a good idea, but I found, after years of rejections of my four attempted novels, that an editor at GP Putnam’s had given my agent a contract on the spot after reading my letter. I got my comeuppance when I delivered the ms. to him 15 months later and he asked me to remind him why he’d ever wanted to buy that book.

DGE: I love your story about the letter you sent Bellow, and his response. Do you mind sharing that again?

ST: As it happens, I exchanged a few letters with Bellow. The first came when I was a writing fellow at Stanford, and I was moved one morning to let him know how much I appreciated his work. Somehow in the letter I mentioned my belief that he had “a warm Jewish heart.” That was the phrase Bellow responded to when he wrote back. But in subsequent years, I wondered if one reason he answered was because he recognized the last name, having known my father. When I was in law school, he won the Nobel Prize and a friend of mine at Rolling Stone commissioned me to interview Bellow for the magazine. I got no answer to my letters and finally thought of calling him person-to-person at his office. I recognized his voice immediately and began pouring my heart out and explaining my qualifications. The operator interrupted suddenly. “Wait a minute, wait a minute,” she said, “is this Saul?” Bellow said yes with an air of defeat, but still said no to me during a brief ensuing conversation. The operator’s insistence on doing her job, Nobel Prize be damned, reminded me of moments Bellow created, reflecting the so-called tyranny of petty bureaucrats, including a lovely reversal in Herzog, when an African-American police officer stops Moses Herzog on Lake Shore Drive and addresses him as “Moses.”

Years later, I was invited to meet Bellow by a mutual friend and turned down the opportunity. By then I was convinced that certain writers are, in the phrase, ‘better read than met.’

DGE: Your first book, One L, explored your law school experiences. Ten years later, already a lawyer, your first novel, Presumed Innocent, arose from your courtroom experiences. You’ve always been a lawyer/writer or writer/lawyer. I imagine your legal career could have gone forth as a solo enterprise. But what about your writing career? What would it be without your other job?

ST: One L was a solid success for a first book. I’d gone to law school vowing that I would remain a writer, but I was both enchanted by the law and reluctant to relive the agonizing experiences I had at Stanford, when I felt I was trying to tear the work out of myself. So I decided to move on to practice and was lucky enough to land a job at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Chicago. Almost every current or former Assistant U.S. Attorney will tell you that it’s the best legal job imaginable, full of meaningful work and talented comrades. It’s also a consuming enterprise, and finding the time to write with a young family was difficult. The only periods available, when I was not engulfed with thoughts about my cases was thirty minutes on the morning commuter train and a couple hours late on Sunday nights, after everybody was asleep.

In those hours, during my first years as an AUSA, I wrote yet another unpublished novel. It attracted some interest in New York, but I shifted away from it in favor of a new effort about a prosecutor. My job left me teeming with emotion every day, feelings that I needed to explore on paper. The idea that the prosecutor in that story would end up accused of the murder he was investigating came along as I writing, and was inspired in part by a call by the same literary agent who had sold One L. I told her what I was working on and she interrupted me to say, “Well, there’s a trial in there, isn’t there?” I was always too buffaloed by her to say no. Ultimately, I kept the idea of the trial but decided to leave the agent, in favor of Gail Hochman who had been the editorial assistant while I was writing One L, and who had given me solid advice throughout. She has continued to do so for more than forty years.

DGE: Courtroom lawyers need to master oratory and writing skills. You write briefs and lots of other legal documents, but I’m thinking about the trial lawyer.

Your remarks, as well as your line of questioning, are meticulously prepared, but you must bring those scripts to life in order to persuade and move a jury. In your novels, your masterful use of dialogue sculpts characters, creates tension, moves plot, and grounds the reader in the world you’ve created. I’m wondering what lawyer skills you bring to the page.

ST: Practicing law immediately informed and improved my fiction. In trying jury cases I learned a great deal about how to address a popular audience, which I’d decided at Stanford the best fiction did. (I had horrified one of the senior members of the English Department by saying that the best literature should engage both an English professor and a bus driver). There were valuable practical lessons. I learned how to cut, sometimes savagely, in order to meet a judge’s page limits for a brief. The milieu of the law offers constant exposure to amusing characters and intriguing plots. By contrast, as I often tell my friends, it’s much easier to write cross examination than to do it in a courtroom, since the author gets to make up the answers, as well as the questions.

But nothing mattered more to my writing than the true project of the law. I always say that going to law school was the great break of my literary career, because the conflicts at the heart of the law reverberate so deeply in my core, as I sensed when I chose law over academia. I am ever fascinated by the law’s central questions, determining what is right and what is wrong, issues which are always judged in a practical dimension, requiring the answers to be embodied in rules that are flexible but fair. As I have often said in my novels, the law is about the little bit of life that humans can actually control, and trying to submit those matters to the regime of reason. For all the law and lawyers many failings, that still strikes me as a noble enterprise.

DGE: Kindle County. Tell me about its birth, in Presumed Innocent, and its evolution. Why not call it Cook County and be done with it? You’ve told me before that at some point you created a whole Kindle County map in your office, to keep track of the geography. Thirteen novels in, that must take up all four walls.

ST: Kindle County was purely an accident. To give myself a comfortable distance from my present workplace, when I started Presumed Innocent I drew on my experiences in my last year of law school, when I worked in the Suffolk County, aka Boston, District Attorney’s Office. But I’ve never been a diarist. I found as I was writing Presumed that I was pumping the savory details I was absorbing in the office into the novel. Eventually, of course, the city I was writing about looked more like Chicago than Boston, so I gave it another name, a city much like Chicago but more Boston’s size. My second novel was about a character from Presumed Innocent, Sandy Stern, the defense lawyer, so I was more or less forced to stay in Kindle County. But I found myself at home there as the lore of Kindle County expanded. My beloved former editor, Jonathan Galassi, is the one who gave me the map of Kindle County. I refer to it often, but still live in dread of contradicting myself, something I have often been saved from by sharp-eyed editors and loyal friends.

DGE: The mental image I have of your home workplace is vastly different than the one I have of you on the L as it clacks and tunnels its way south to your office and north after you leave work. How has your writing life changed, initially after the huge success of Presumed and over the years? What is your routine like now?

ST: You have to remember that after PI, I continued to practice law full-time and did until I finally asked my firm to agree to a part time arrangement in 1990. Of course, with the success of Presumed, we put an addition on the house, which we dubbed, with a brass plaque, “Hochman Hall,” in honor of Gail. So I finally had an office at home, where I worked for many years, usually writing in the mornings and going to the office in the afternoon. One gift I found I had was that a client could call me at home during the writing hours and, once the call was over, I could resume writing exactly where I was when the phone rang. BUT, I still wrote on the Chicago Northwestern on my way to the Loop every day. Never on the way home, though. My head was full of law by then.

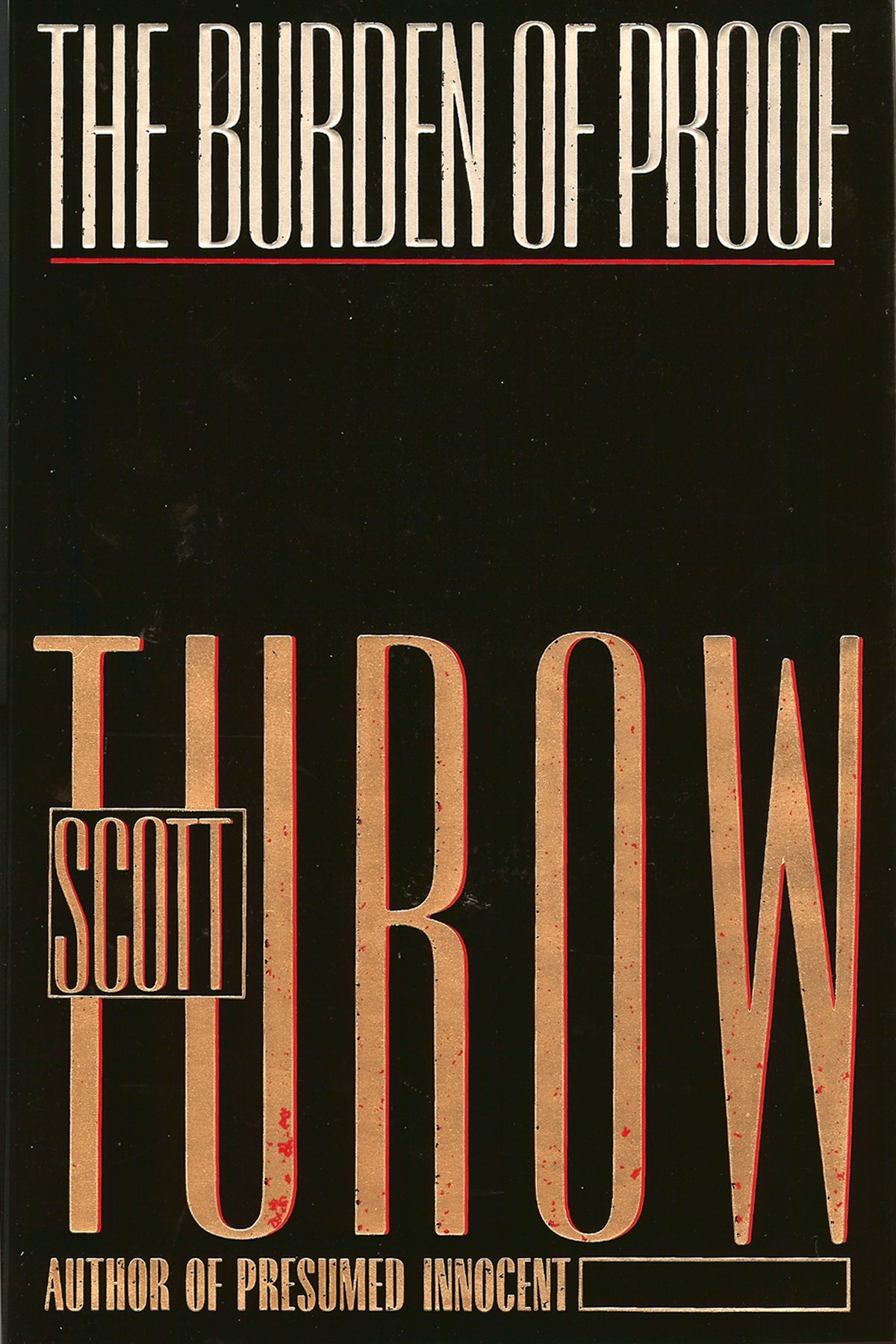

DGE: In the opening sequence of your second novel, The Burden of Proof, the narrator calls Chicago “that city of rough souls.” That simple line seems to capture your authorial approach to place—that the city somehow imposes itself on the interior lives of its people, and in turn the people determine the character of the city. Tell me about Chicago as it relates to your fiction and your life.

ST: When I was at Stanford, even though I liked much about Northern California, I confessed to friends that my dreams were still set in Chicago. Although we spend barely 100 days a year in the Chicago area now, it remains the emotional center for me, the city where I grew up, the city around which I raised my children, and the city about which I’ve written so much, including through the guise of Kindle County. I have always insisted the Chicago is the most American of our large cities. New York—well, how can it really be a quintessentially American city, where so few people drive? LA is high on its own glitz. Chicago has always been about work and working people, the work that most people do, whether the stockyards where my grandfather once labored, or the huge service industries that employ so many today. We are, to steal a phrase from the great William Gass, “the heart of the heart of the country.”

DGE: The adoring critical reception of Presumed, combined with the impressive commercial sales...many would say that this was your breakthrough. That’s true enough, in terms of your ability to dictate the terms of your career. But I knew that you were an artistic force—one here to stay—when I read The Burden of Proof. You’re writing in a more-or-less prescribed genre, the legal thriller. I’ve found that an author’s first entry into such an arena is often their best—after that, the expectations and confines of the form often dull the output. I can think of many, many authors I truly enjoy, but in a limited, strictly-for-entertainment fashion. Not you. It’s not necessarily that I thought Burden superior to Presumed as much as I thought it was distinct. I knew, at that point, that the form would not inhibit your ability to tell compelling, important stories, and that there was surely a bounty of rich stories for you to tell. Go back to that time in your career and give us a sense of your artistic goals in the wake of early success.

DGE: The adoring critical reception of Presumed, combined with the impressive commercial sales...many would say that this was your breakthrough. That’s true enough, in terms of your ability to dictate the terms of your career. But I knew that you were an artistic force—one here to stay—when I read The Burden of Proof. You’re writing in a more-or-less prescribed genre, the legal thriller. I’ve found that an author’s first entry into such an arena is often their best—after that, the expectations and confines of the form often dull the output. I can think of many, many authors I truly enjoy, but in a limited, strictly-for-entertainment fashion. Not you. It’s not necessarily that I thought Burden superior to Presumed as much as I thought it was distinct. I knew, at that point, that the form would not inhibit your ability to tell compelling, important stories, and that there was surely a bounty of rich stories for you to tell. Go back to that time in your career and give us a sense of your artistic goals in the wake of early success.

ST: Commercial success was the furthest thing from my mind during my years at Stanford and even when I was writing Presumed Innocent, which I was afraid would prove too literary for the mystery crowd and too much a mystery for the literati. Its success flabbergasted me, particularly the sales. But I saw that success as an opportunity to write books that are driven by the kind of psychological realism that had always seemed to me to be the heart of the novel. I love Rusty Sabich, love his voice, love his messed-up psyche, but I knew that if I wrote another novel about him next, I would pigeonhole myself in a way that I would always regret. I have tried to do something different with each book. Friends who are far more successful commercially told me a long time ago that I was blowing it if I didn’t write a book a year. I just can’t do that and create books that I’m proud of, which, of course, is essential to me.

DGE: Your reading has always gravitated toward high-minded—serious, for lack of a better term—literature. You never studied or much consumed popular fiction. What impact did your reading habits have on your literary style and choices?

ST: The English novelist Carey Harrison wrote me a letter after reading The Burden of Proof and said he could feel the influence of Bellow, and I could not have been happier that someone finally noticed. I absorbed a lot from the novelists I idolized—Updike’s use of the present tense in Rabbit Run; the elegant plotting of Graham Greene; the moments of intense emotion realized by Tillie Olsen—but by now I recognize my voice as my own.

DGE: The popular fiction that gives bestsellers a bad name—at least to a certain class of readers—often feature stock characters. Characters who do what their vocation demands they should do. There is SO MUCH to say about the quality of your characters, but I’ll try to focus on just two aspects.

The first is how nuanced and varied your characters have been over the course of your writing. Starting with Rusty Sabich and going on through Pinky Granum, there is a whole population of thoughtful, conflicted, sometimes contradictory characters. I hesitate to use either the word “villain” or “hero” here, because there are few easily defined good and bad guys in your stories. Is this nuanced approach deliberate, or a manifestation of your own perspective on people and their behavior?

ST: When Sydney Pollack, a wonderful man and filmmaker, who bought the rights to Presumed Innocent, came to see me, he said, ‘I’ll give you one thing I won’t change.’ I answered, ‘The shades of grey.’ Being a prosecutor—and practicing criminal law, in general--has taught me a lot about the nuances of human behavior. There are people who do bad things; and some will do them again and again. But even those people often have something to commend them. Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about Brian Dugan, who committed the horrible killing of Jeanine Nicarico, for which Alex Hernandez and Rolando Cruz had been convicted and sentenced to death, when Dugan was arrested for a similar crime. Why did he tell the authorities who questioned him that he was the true killer of Jeanine, when he knew that he would skate for that crime if he kept his mouth shut? For all his psychopathy, Dugan refused to allow two innocent men to die or do time for a crime he knew he committed, and he stuck by that for years. That’s a pretty striking example of the heroism and villainy that I regard as inhering in all human beings (Dugan’s reward, by the way, for doing one truly honorable thing was that after a decade of denying Dugan’s guilt, the DuPage State’s Attorney finally reversed field, tried him for Jeanine’s murder and attempted to put him to death.)

DGE: The second aspect is vulnerability. As a reader what invites me into the worlds of your creation are the characters, particularly the narrators, who struggle to keep their own lives together. Infidelity, aging, greed, ambition, deception, lust and infatuation—these are some of the traits of your more honorable characters. Tell me about your process for shaping these complicated characters, the interplay between their surface and hidden lives, and of how you manage to still make them likeable.

ST: I start from the place we were discussing above, that no one is either all darkness or all light. Our motives are always multi-layered and even sometimes contradictory. But I never get very far into a book without assuring myself that I really understand what drives the people I am writing about. In my most recent novel, Suspect, Pinky Granum, the main character, is 40 years younger than I am, female, bisexual and a little more cavalier about breaking the law than I’ve ever managed to be. But as different as she is, as far as some of her experiences are from my own, I started out with a sense of this young woman’s poignant struggle to come to terms with the fact that she was always going to strike many people as strange, and to accept that about herself without shame.

DGE: There is so much ground to cover between your first and most recent novel, but I’ll try to be compact.

Jeremy Treglown, reviewing your third Kindle County novel, Pleading Guilty, for The Independent, said it was “one of those apparent contradictions in terms, a suspense-thriller which asks to be read more than once.” He attributes this to “its psychology.” Talk a bit about the psychology of your novels.

ST: The glory of narrative is its moral dimension, its ability to teach us to do unto others because of what they share with us. And that in turn depends on being able to believe their emotional lives. The more we are persuaded by the depth of a character, the more we believe her or him, and the more we care about their struggles. The ability of fiction to stir us deeply depends on intense psychological realism. Or at least that’s true for the books I want to write. My mother’s brother, my beloved uncle, was a psychoanalyst and so I was schooled in Freudian theory, which I still accept, with some qualifications. But I have always accepted the idea that our minds work on many levels, that “feelings” are rarely unitary, i.e. we actually ‘feel’ many responses at the same time, and that often our deepest motives are suppressed or hidden to us, as incompatible with who we think we are or want to be. I hope my characters reflect all of that.

able to believe their emotional lives. The more we are persuaded by the depth of a character, the more we believe her or him, and the more we care about their struggles. The ability of fiction to stir us deeply depends on intense psychological realism. Or at least that’s true for the books I want to write. My mother’s brother, my beloved uncle, was a psychoanalyst and so I was schooled in Freudian theory, which I still accept, with some qualifications. But I have always accepted the idea that our minds work on many levels, that “feelings” are rarely unitary, i.e. we actually ‘feel’ many responses at the same time, and that often our deepest motives are suppressed or hidden to us, as incompatible with who we think we are or want to be. I hope my characters reflect all of that.

DGE: Your novels are considered “stand-alones,” meaning independent of one another. I guess the exception is Innocent, which you wrote as a sequel to your debut novel. Yet, Kindle County and its denizens mature almost in real time. Tommy Molto appears in at least four novels, Rusty Sabich graduates to chief judge of the Court of Appeals, Sandy Stern pops up in many of the stories, Pinky gets flushed out in her second appearance…then there are great characters like Dixon Hartnell, Squirrel Gandolph, Larry Starczek, Mack Malloy, and Evon Miller who enter and exit at particular moments in time. I’m reminded of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, Hardy’s Wessex, maybe even Baum’s Oz, though that’s a bit of a stretch. You’re not just sticking to a certain imagined world, you’re building it brick-by-brick, character-by-character. This has gone on decades now. What continues to drive you in that direction? Is it comfort, or do you feel there is a certain power in working this setting to its maximum advantage?

ST: I think a novel is more than itself when it gains meaning from prior books. It rewards readers who have previously been acquainted with George Smiley in LeCarre’s novels when he reappears, especially since the reappearance deepens him as a character. Tommy Molto’s transformation across four novels is one I took special pleasure in. He was landlocked emotionally until his mother’s death, then became a husband and a father and far more compassionate human being—and a better prosecutor as a result. The fact that regular readers can understand that evolution is, I hope, a bonus to them, and also faithful to the way our understanding of the people in our lives evolves.

DGE: Ordinary Heroes does not follow this pattern. This 2005 novel is largely set in the European Theater. Still, some minor characters hail from Kindle Country. What led you to write this novel, and what made you give these Kindle County characters a small presence?

ST: There’s a Kindle County thread, as you note. David Dubin is the father of journalist Stu Dubinsky, the ostensible narrator of Ordinary Heroes, and a character who first appeared in Presumed Innocent. So I was faithful to the plan you note above. But the novel was intended primarily as a way to come to terms with my father. David Dubin, as a person, is far more like my father’s older brother than my dad, but his path across Europe as part of Patton’s Third Army is identical to my father’s, as I traced my dad’s movement from his letters. I could not understand how the man who raised me could be squared with the humble heroic figure who emerged in my father’s stories about his war experiences. The answer, probably obvious to an outsider, is that many of those stories were untrue. I was chagrined, but my dad remained enigmatic to the end, because his wartime actions were far braver than any act I’ve performed in my life. As far as I was concerned, he had every right to think of himself as a hero. It’s a comment on his insecurities, perhaps traceable to his mother’s death when he was four, that he felt the need to embellish.

DGE: You hear writers say it’s impossible to choose their favorite book—it’s like giving birth and so on. I understand why nobody wants to single out a child at the expense of their siblings, but your books won’t be offended. Which is the one you love most?

ST: Some novels please me more in retrospect, I’ll admit that. But that list remains pretty long. Presumed Innocent, The Laws of Our Fathers, Personal Injuries, Ordinary Heroes, The Last Trial.

DGE: In advance of the Fuller Award ceremony at which the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame will honor you for your lifetime achievements, I’ve watched and read many hours of interviews for which you sat down. You’re ever thoughtful and interesting, as well as gracious. But all these years in, the questions get a bit repetitive; you’re forced to repeat answers, re-tell the same stories. We’re doing it here again. Do you recall a moment when a question surprised, maybe even stumped, you? What was it, and do you remember your response?

DGE: In advance of the Fuller Award ceremony at which the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame will honor you for your lifetime achievements, I’ve watched and read many hours of interviews for which you sat down. You’re ever thoughtful and interesting, as well as gracious. But all these years in, the questions get a bit repetitive; you’re forced to repeat answers, re-tell the same stories. We’re doing it here again. Do you recall a moment when a question surprised, maybe even stumped, you? What was it, and do you remember your response?

ST: I wish. I am grateful to every interviewer who takes the trouble to prepare, I truly am. Your questions, Don, have been incisive and thoughtful. And I know you weren’t fishing for compliments. But your question above, about what I feel I’m accomplishing with the reappearance of certain characters is one I’ve been hoping to answer for a long time.

DGE: I’m delighted that the CLHOF chose you to receive the Fuller. It’s meant to be a celebration of our finest, most important living writers, and you certainly belong in that class. When I first imagined these ceremonies, I thought of how writers, unlike musicians, don’t have a built-in way to pay homage to their heroes. So this is a bit like our literary rock jam. As a member of the Rock Bottom Remainders, I know you know a thing or two about a star-studded jam. What are your thoughts and feelings as you approach this evening?

ST: Jeez, I’m going to have nothing left to say when I get my chance to speak. First, of course, I am very much aware that as nice as this honor is, it’s also a reflection of being, well, old. More to the point, I spent a long time in the literary desert, logging a lot of pages with not a whole lot to show for it in terms of literary success. I am, therefore, deeply conscious of the role of luck in my career and life in general. I have worked very hard and unlike some writers, I love the writing process. But starting with my days at Stanford, I have known a huge number of talented writers whose outstanding work did not get the audience it deserved. I remember many of them with enormous appreciation and wish that were more broadly shared. So I approach this kind of event with enormous gratitude for my own good fortune.

Donald G. Evans is the author of a novel and story collection, as well as the editor of two anthologies of Chicago literature, most recently Wherever I’m At: An Anthology of Chicago Poetry. He is the Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.