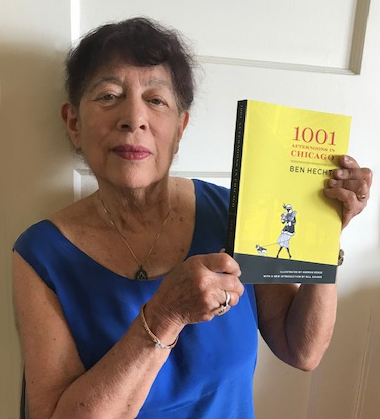

A Chicago book that holds special meaning to me

Rosellen Brown

Although he was born on New York’s Lower East Side and raised in Racine, Wisconsin, Ben Hecht (1894–1964) has always epitomized both the energy and the cynicism we have forever associated with Chicago; he called it “the city of my first manhood.” He arrived in 1910 and quickly became a newspaperman—journalist would have been too fancy a name for his rough-and-tumble attention to what he called the “haunted streets, whorehouses, police stations, courtrooms, theater stages, jails, saloons, slums, madhouses, fires, murders, riots, banquet halls, and bookshops.”

His play “The Front Page” (which later became the ever-popular film “His Girl Friday”) magnified the verbal pandemonium of a newspaper office to demonstrate just about every human behavior except, perhaps, tenderness. Brash, restless and tirelessly inventive, Hecht eventually removed himself to New York and then to Hollywood, and with mythic productivity wrote novels, plays, stories and an unstoppable but significant riot of screenplays. But while he made his home here, he worked at the Chicago Daily News, which gave him a paycheck for pursuing his curiosity about a wild variety of lives.

In 1921, according to his editor Henry Justin Smith, “He had been divorced from our staff for some weeks and had married an overdressed, blatant creature called Publicity. Well, and how did he like Publicity? The answer was written in his sullen eyes; it was written on his furrowed brow and in the savage way he stabbed the costly furniture with his cane…The alliance with Publicity was an unhappy one….Easy work, short hours, plenteous taxis, hustling associates, glittering results…He just unaccountably, illogically and damnably couldn’t stand it.” His old job, Smith told him, was still open. But no, no, he had a new idea. “Something different. Maybe impossible.”

Although the title came later, what became Hecht’s 1,001 Afternoons in Chicago might not have been conceived to keep him, like Scheherazade, literally alive, but in another sense it gave him a soul-saving way to express a suppressed side of himself. Every day he simply told another story that featured a Chicago character, not heroic, not politically enmeshed, sometimes typical, sometimes unique. Featured on the same page as the comics, they were not opinion-driven like the work of so many of today’s daily columnists, nor fixed on a single character like Mike Royko’s later Slats Grobnik. The closest today’s newspapers might come to these little story/essays is the current habit of introducing news stories by focussing on a single person.

But these were not prologues to the news; they were shapely, sympathetic, often enigmatic glimpses of individual men and women (somewhat more of the former than the latter) who walked the streets or sat at the tables or lay awake at night in the metropolis that throbbed around them oblivious to their pain or confusion or, though more rarely, delight. They were accompanied daily by striking pen-and-ink designs—not exactly illustrations, more like stylized woodcuts—by a Dutch-born artist who taught at the School of the Art Institute named Herman Rosse.

So, overseen by a narrator who simply calls himself “the newspaperman,” we have glimpses of Fanny, a denizen of the night, who stands before a judge guilty but not repentant, in violation of section 2012 of the City Code; there is Tobias Woodenleg; Mr. Sarz, a Russian-Jewish businessman apparently flush enough to buy a round for the entire house, who turns up the next day drowned. We meet revolutionaries plumping for “the same terrible misfortune to happen in this country that happened in Russia.” Countless immigrants, flappers, performers, enthusiastic shoppers, fishermen rapt on the shore of the lake and Mrs. Sardotopolis who has eight children about whom she thinks “as long as they made noise they were healthy” until one, little Joe, goes mortally silent. Quite a few stand before judges, most likely because that was a convenient way for the newspaperman to observe the way so many of these little lives were enacted at the rough edge where their dramas met the law.

“There are two lives people lead,” Hecht wrote. “One is the real life of business, mating, plans, bankruptcies and gas bills. The other is an unreal life — a life of secret grandeurs which compensate for the monotony of the days….And we live for a charming hour through a fascinating fiction in which things are as they should be and we startle the world with our superiorities.” He’s on to us, this modest but observant book shows us, and—though his own life later tended toward the flamboyant and the glamorous, achievement piled on achievement — his clear-eyed (if sometimes sentimental) portrayals are rooted in real sympathy and an enthralled tolerance for both the everyday and the outlandish.

The University of Chicago Press has reissued a handsome paperback reproduction of Hecht’s original, emphatic ink drawings intact, with a very fine, context-setting introduction by Bill Savage, Chicago’s most devoted commentator on the texts that define our city. He says of Hecht, and so much more, that this “cosmopolitan explorer”… “engages in the quintessential act of urban imagination: he imagines what it might be like to be someone else.” To me, that captures in a single phrase the work and the pleasure of every writer of fiction. 1,000 Afternoons in Chicago brings the city’s strangers close to us. We will forever need books like it.