A Chicago book that holds special meaning to me

Mark Adams

In the sweaty summer of 1994, when my experiment of trying to make it as a writer in New York was looking like it could go either way, right around the time my beloved White Sox bailed on their season to go on strike with a one-game division lead, I was walking through Soho when I saw a half-price copy of three Nelson Algren books in a single volume. I was working at GQ Magazine as a fact-checker, and had just verified whatever facts one could in a piece by Richard Merkin, the painter and bon vivant who also wrote quirky nonfiction that took a lot of creative liberties. Merkin had mentioned the Algren trilogy and, hearing I was a Chicago transplant who’d spent some time working in a slightly seedy precinct along the river, suggested I check it out.

Three for the price of one is precisely the sort of sweet-smelling enticement that would lure one of Algren’s suckers into a pitcher plant from which he slowly realizes there’s no escape. With no baseball to watch, I found myself with twenty extra hours a week to zip through two of his best-known novels, The Man with the Golden Arm and A Walk on the Wild Side. Even lighthearted Algren works are about as cheerful as Jude the Obscure, but I found something soothing in reading tales of con men, housebreakers, crooked cops, drunks, derelicts and assorted jagoffs (as we used to say), all struggling just to get through the day as I was.

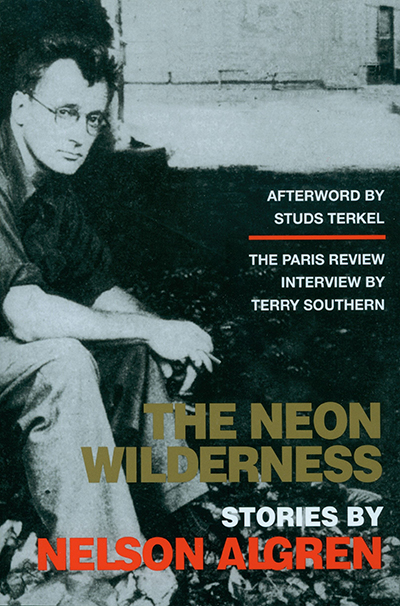

It was probably Labor Day, the most Algrenesque of national holidays—you can imagine a hundred of his unhappy couples, drinking Old Style at the kitchen tables of their three-flats and listening to the parade on the radio—that I got around to The Neon Wilderness. It’s a collection of short-stories, a flip-book of scenes from “the city on the make,” as Algren later famously put it; imagine a Raymond Carver collection in which fewer characters sit through uncomfortable silences and more of them get clobbered with heavy objects on Milwaukee Avenue or have their pockets picked on the El. Drunks complain about the oversalted pretzels and beat the crap out of each other “to fill the emptiness of their lives as they filled their empty glasses.” The story that sticks with me most half a lifetime later, “The Face on the Barroom Floor,” features a legless card sharp who pummels a smart-mouthed bartender who has besmirched the honor of his peep-show girlfriend. Who else but Algren could pull this off? Who else would try? The denouement is even more gruesome than the title suggests.

The Neon Wilderness is a book of parables. The lesson of each, much like that of following a pathetic sports franchise, is that life is strange and sorrowful and will crush your soul. Maybe you’ll catch a break, probably not.

That autumn, I wrote a short story heavily influenced by Algren, which, while not very good, caught the attention of an editor who gave me an assignment that led to a job that led to a career. Largely because I judged a book by its cover.

I never did forgive the White Sox.