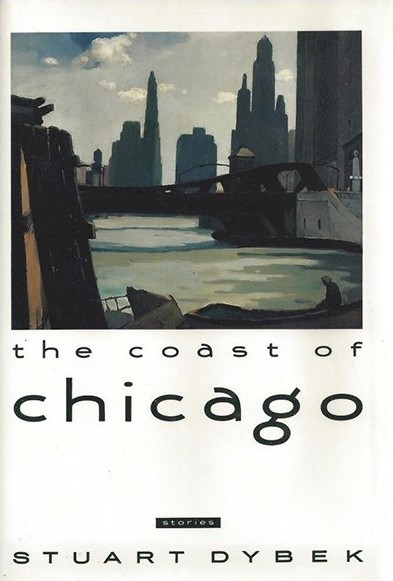

A Chicago book that holds special meaning to me

Christine Sneed

One of the pleasures of reading the short fiction I love most is how immersive it is, and how specifically it evokes the time and place in which the events and characters are located. Stuart Dybek’s The Coast of Chicago—a story collection that has lurked very close to the front door of my mind since I first read it years ago—is one of those books that makes me feel most hopeful and alive. Like his indelible characters, I too get to scavenge for bottle caps in reeking alleys and drag race past bars named Fox Head 400 and Edelweiss Tap when I read these stories.

Michael, the little boy in “Chopin in Winter,” who learns from his dying grandfather about music and the loneliness it can both express and assuage, is probably the character in The Coast of Chicago I think about most often. Michael’s father was killed in World War II a few years before the story opens, and so he also bears witness to his mother’s lonely suffering. Somehow, his point of view remains a child’s throughout much of the story he narrates—a wry, almost impartial voice that reports on the alternately flimsy and opaque mysteries that motivate the actions of the adults around him. I don’t know how Dybek did it, but there it is.

One coincidence before I conclude: I lived for two years, not long after 9/11, in the same building where Andrei Babovitch, the friend of the narrator of “Farwell,” lived.